Place de la République is a central meeting point in Paris. Several underground metro lines stop at its station, and its wide-open square is a gathering place for many people, particularly younger people. When you first enter the square, there is a flurry of activity, but it never feels overly crowded. Suppose you are there in the spring, summer, or early fall, on a sunny day. In that case, you get a sense of a common place, a transitory and ephemeral space in which the citizens of Paris change their destination or escape the metro into the warrens of streets surrounding the square, with its restaurants and the click-clack of skateboards landing on its pavement.

Place de la République is a place where people occasionally assemble, protest, and eulogize tragic events such as the Paris attacks in 2015, with Marianne, the anthropomorphized symbol of France, presiding over all in sheer, statue-like form, arm aloft, eyeing the horizon above. Spaces like Place de la République in France hold a special place in French social history. They act as a potential catalyst for change and, for the most part, lie dormant until they are called upon for congregation. There is a charge in spaces like this, one that is speculative, but carries the gravity of potential upheaval before change.

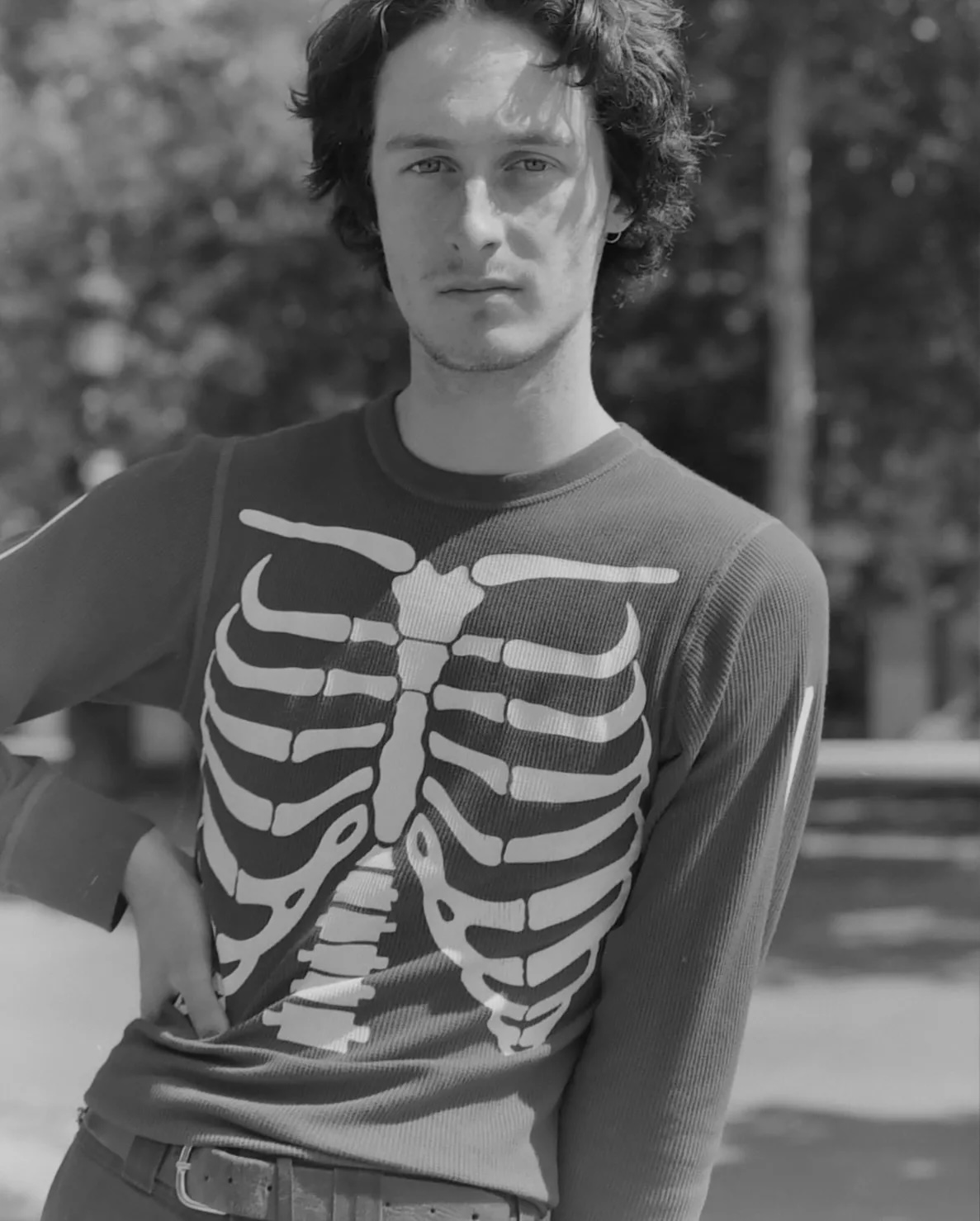

Thomas Boivin has been quietly whittling away at a substantial record of Parisian life for quite some time now. He has quietly been documenting the citizens of Paris in different arrondissements. His previous books, Ménilmontant and Belleville, are shaped by a consistent monochromatic investigation of both places through the people who walk their streets. One unifying theme in Boivin’s work is his sense of light, reminiscent of Thomas Roma, Sergio Purtell, and Mark Steinmetz, amongst others. His full frontal photographs in the new books remind one of Judith Joy Ross a bit more. They limit the scale of the Place de la République itself by showing people consuming most of the frame, with slivers of architectural and social life hinting at around the curves of shoulders, headphones, and hairlines.

Most of the work concerns younger people making thrier way through the city and though the emphasis is still on place, the question I come away with is how this generation of young Parisians will accommodate the enormous challenges in their social, economic, and political life over the coming years. It is a daunting task, though this is not necessarily implicit in the portrait itself, but emerges when one considers the catalog in its entirety or aggregate. Boivin manages to create images that allude to this vulnerability without feeling intrusive, which is especially difficult when using a 4×5 camera on a tripod. The grace and effortlessness of most of the portraits suggest that those caught in silver are comfortable with his request to photograph them. Some light turns of expression suggest this, and a few that are quizzical, even defensive, in some small readings of the faces of passersby in front of his camera suggest uncertainty. This is essential as the subtlety is what drives the images to perform for the reader. If it were a book of happy smiles or if a generic expression flatlined everything, it would miss the point of the individual image.

I tend to think of Boivin’s work as having a sweetness. I am reminded, and I have mentioned this before, of Robert Doisneau and the history of French Humanism in his work. As I have explained before, that trope of photograph making, mostly conditioned to the post-war period and into the 60s had lost much of its popwer by the 80s and has laid relatively dormant in contemporary practice until quite recently with a new emphasis of looking at people with a senstive eye again, which is no doubt a product of the tumult and castastrophe of the tiems we are presently facing. Holding onto each other in an age of artificiality, warfare, and economic uncertainty seems increasingly rational. Without the saccharine sentimentality, we need to find a way to work collectively against the grind of systemic forces seeking to control our destinies. I know it sounds woefully embedded with platitude, but it is either that or the stangelhold of cynicism, and cynicism is one of the more disappointing qualities of human behaviour.

I look forward to seeing where Thomas points his camera again. I thoroughly endorse his efforts as a chronicler of the times through the portraits of our collective age.

Thomas Boivin

Place de la République

Stanley/Barker