And then there was the night—archives from the edge of hell—chimerical dissonance—six cloven hoof Satyrs. Bachanalian. Excremental. Grain, dissolve. Pushing the sword of Damocles in until the hilt fractures on the bone of the pubic mound. A horsehair away from piercing the veil. Scrutinize, Labotomize. Forever roam. Necessarily hexed, vexed, encouraged by nebulous worlds colliding. We all want our time in hell. We all need our time in hell. Morning star, let the day begin…

“In the violence of overcoming, in the disorder of my laughter and my sobbing, in the excess of raptures that shatter me, I seize on the similarity between a horror and voluptuousness that goes beyond me, between the ultimate pain and an unbearable Joy”. -GB

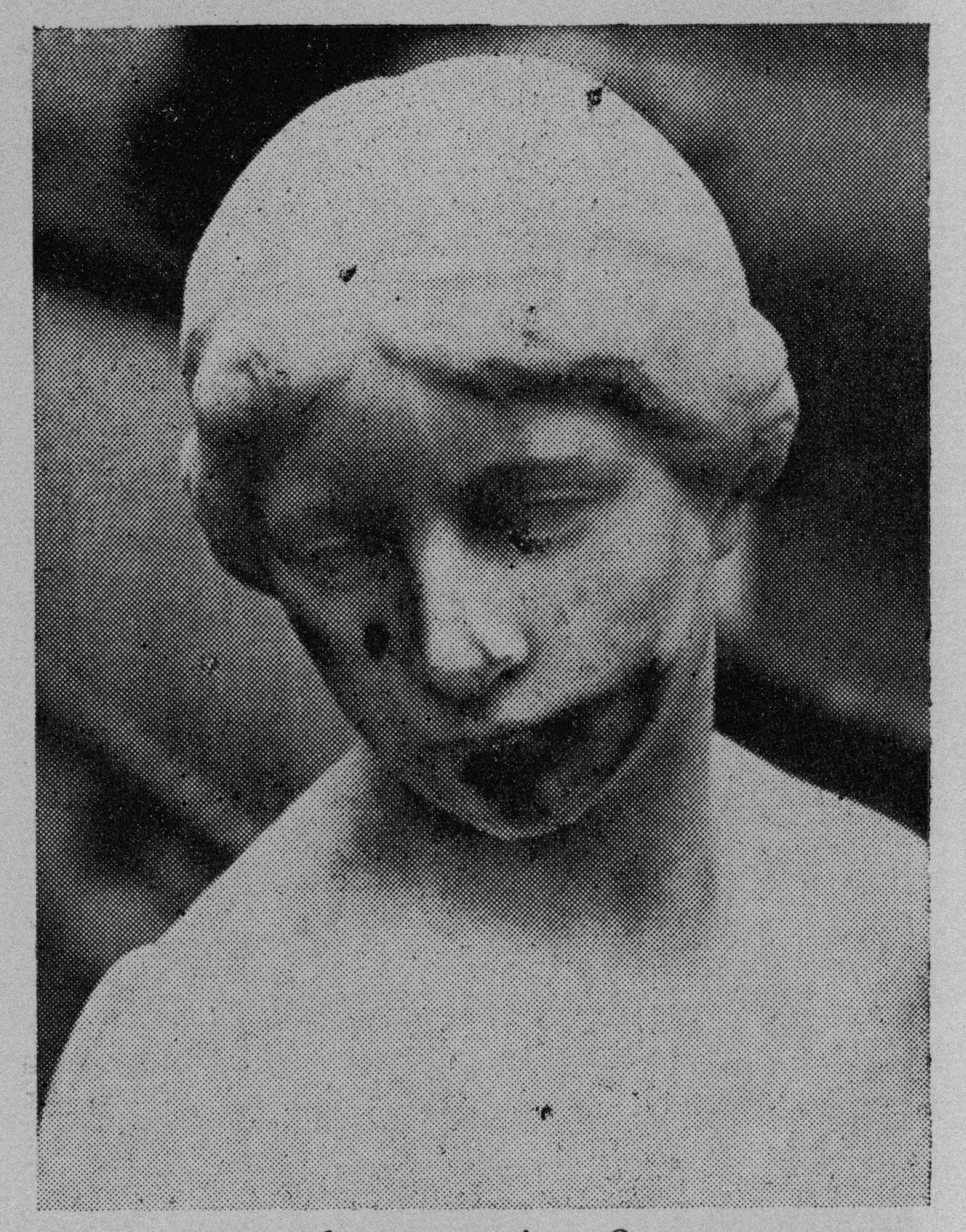

A metamorphosis. Agalmatophilia is an atypical disease of the retina. Necroses, a love of statues. All that is torn is but a symbol in the wake of human vanity. Here we may bloody thumb through the carcass of empire. Each titular file is an excuse to inherit a blood libel. Adam Weishaupt. Bavarian Illuminati. Ritualized innuendo, sacrifice, a demiurgency. To bring into being the essence of violence, and extreme discipline bordering on enduring love. A thorny rose clamped between loose gray teeth, gums in disarray, the dirty, corroded metal bit tight, fastened down with thumb screws, a diminutive and unnatural human pony. A blackened hymn to the republic. The monkey on your back: Henry Fuseli, the prophet, William Blake, moralizing divinian.

All murder, all guts, all fun. Soundtrack, Samhain, November Coming Fire. 1986.

Where it began, or where do we begin, or where have I started my train of thought regarding this spectacularly morose title, And Then There Was the Night, by the collaborative team of Magdalena Wysocka and Claudio Pogo, both of whom are incorporated as Outer Space Press. Initially, I was impressed with the production side of the work. Having explored the duo’s work at a distance and then in a forthcoming conversation, I was intimately drawn to their ability to seize the means of production, as it were, for themselves.

Their output is significant as it is one of self-sufficiency in the day and age when theses DIY and hands-on skills are becoming increasingly necessary to combat the ugly side of several rumblings both in the world’s economy at large, but more significantly with the photobook market itself which seems to be on wobbly legs with market shrinkage and a general fear of spending money on books when the price of eggs is entering into double digits per carton. The world is spinning, yet it is doing so increasingly unbalanced. Being self-sufficient, knowing one’s market size, and producing in the studio while leveraging elbow grease against inflation are already signs of the times and the future of bookmaking, imo.

After contemplating the vital nature of their enthusiasm for producing their own books, I began to delve into their creative process, which, admittedly, is not wholly possible without understanding the exemplary nature of their admirable production. With that in mind, I might suggest that work is multi-faceted and that both authors retain their singular autonomy while creating their own respective work, but they crossover to significant effect when collaborating more specifically on the images. It would be worthwhile for the reader to take time on their site to understand the nuance and drive of each artist to understand their collaboration.

With respect to the book at hand, And Then There Was the Night (2024), the crossover is archival. Both artists share an enthusiasm for found vernacular material, which they reshape into engaging narratives by splicing, cutting, and adding layers to both the subject matter and physicality of the existing work. I am reminded of Katrien de Blauwer’s collages in places, but also some of Dirk Braeckman’s use of found material. On the latter, a significant and shared trajectory might be Braeckman’s book Sisyphus, published by Le Bal in 2015, a work that plays with flash on vernacular pin-up photography, creating a haking effect, reminding the viewer of the source material’s physicality, but also how images are conditioned by light when read. This aspect, which echoes Braeckman’s use of the camera flash, can also be found in Juergen Maelfyt’s flashing of gentlemen’s magazines (though in color).

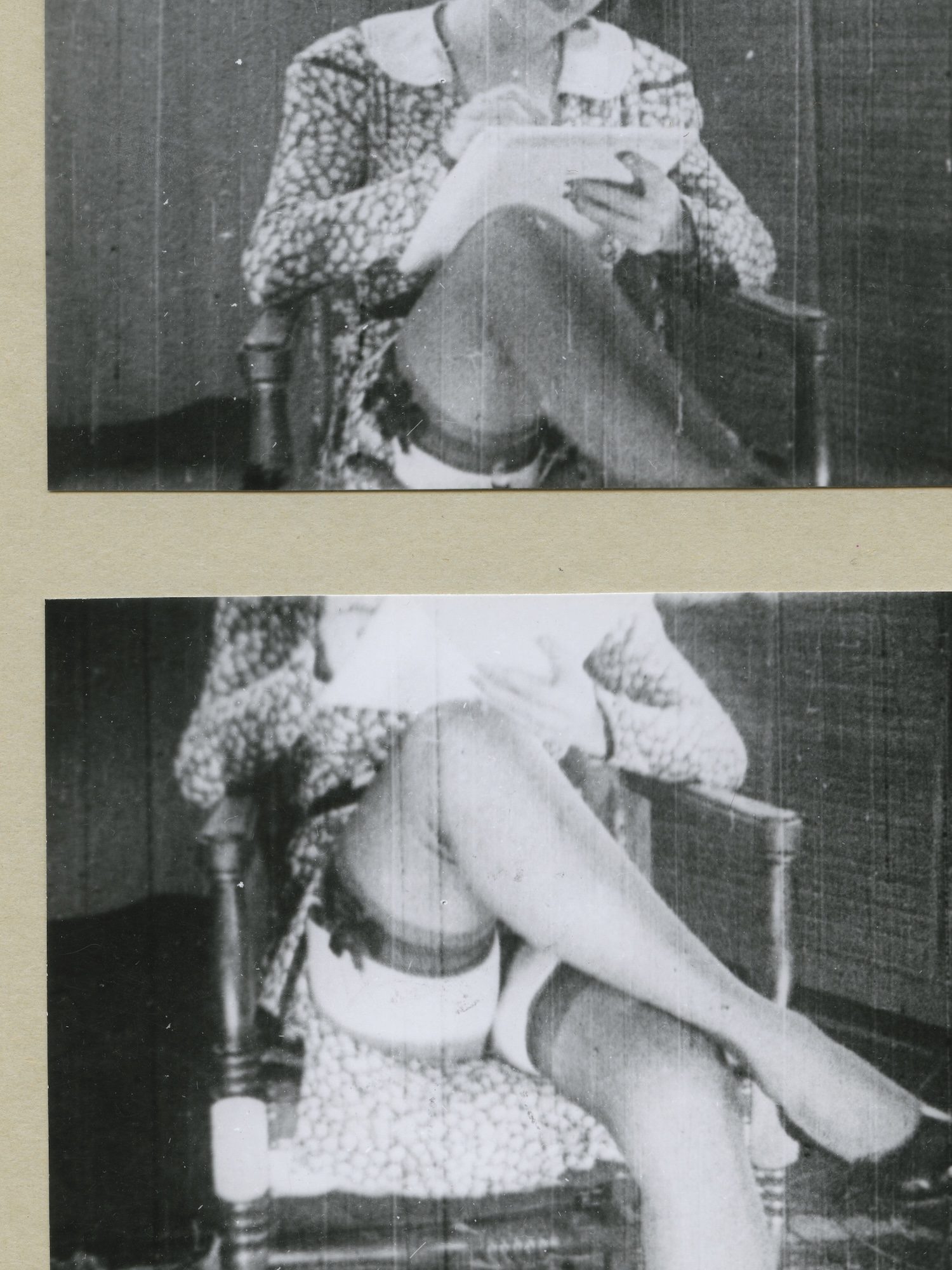

Wysocka and Pogo has made a strange and ethereal type of dirty black grimoire from the material that they have assembled which, by dint of its recording in the book comes from an archive of 1960’70s skin flicks, each still pulled from the film and left in something of a dossier in which the couple have used, along with newspaper clippings regarding a Bavarian witch cult to r]create something wicked, unnatrual, extremely ritualized and pagan. The use of German literature and newspapers profoundly elevates the source material to a new level. It refuses the base sexuality at its heart and instead turns it inward, or on its side, laid on the supine altar, splayed and entered with all manner of necrotic spiritism. The use of text and newspapers is something that both parties share in other projects.

Here, what is fascinating, apart from the psychosis of the grain and the gothic treatment of the subject matter, is how extreme some of the underlying images are if you take the time to sweep away the layers of enforced decay. The satanic element, as it were, here is not taken as a tongue-in-cheek trope of aestheticism, but rather incorporates quite strong imagery, particularly one plate which suggests a dagger finding a female human sheath. The rest of the images also imply a course necrotic feel. There are cold references to statues, but the human body is treated similarly, resulting in a shared approach with photography, perhaps in the works of Braeckman, but also Sudek and Christer Strömholm. I might make some further references to the work of Charcot at Salpêtrière hospital. Didi-Huberman’s book The Invention of Hysteria is worth mentioning, as is Lacan At the Scene by Henry Bond, which explores forensics and attitudes to photography, primarily through crime scene photography, like Eugenia Parry’s book Crime Album Stories. As a final note, I am reminded audibly of the album God and Beast by Non.

To say the book is layered is an understatement. With its tip-ins and layers of imagery embedded in the grandeur of the book’s printing, there is quite a bit of information to consume and digest. The effect is something of a sacrament for the eyes. Regarding the content, it will be more challenging for some people because it is neither light reading nor polite. It involves taking chances and asking the viewer to reflect on themselves and how they interpret the work, both through the lens of the loose association with Bavarian culture and cults, and the history of vernacular aesthetics and the uses and abuses of bodies between pleasure and pain. This hits the right note for me personally in an age where I have found much work in this vein to present as relatively corny by comparison. The role of transgressive image-making as of late has felt like a pastiche, and this sets that problem straight. The book has my highest recommendation, and any serious photobook lover, collector, or enthusiast should pay attention to what the team is cooking—full stop.

Magdalena Wysocka and Claudio Pogo

And Then There Was the Night

Outerspace Press