These are postcards from the lip of a commoditized and disheveled Eden masquerading as progressive life on planet zero. These rasterized observations are the Cliff Notes to the end of natural occurrence and abundance. Everything has a place so long as it has a price or a presence deemed valuable. If it cannot be brokered or traded, it simply cannot be. Value is seen as incremental and exponential. That which has its antecedents in abundance is not redeemable. It has no credit. Being plentiful, or that which eludes commoditization due to its abundance, has no place but under the splintered floorboards, left to rot like a rodent whose tail is caught in the undergirding crossbeams. It has to be made scarce or extractable. Or so we have been taught to understand the principles of progress here on planet zero.

Over the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, we have begun the process of codifying and systematizing all resources on the planet in a vain attempt to prop up the sagging belly of capitalism. We have been taught to understand progressive living as being tied to capital and its governable commodities. In this, we have made conclusions and para-systems that define our realities. These systems are short-sighted and self-imposed, offering invisible masochistic manacles from which we tether our short-term needs to the prospect of long-term loss. We have increased pressure on the natural world to a degree that now seems to have little left, but collapse. We do not see the world as it is, but rather pressure it to become what we want it to be, shaped by creature comfort, plastic in our sperm count, and deformity of untold magnitude waiting to be birthed into a carcinogenic and metastasized monstrosity.

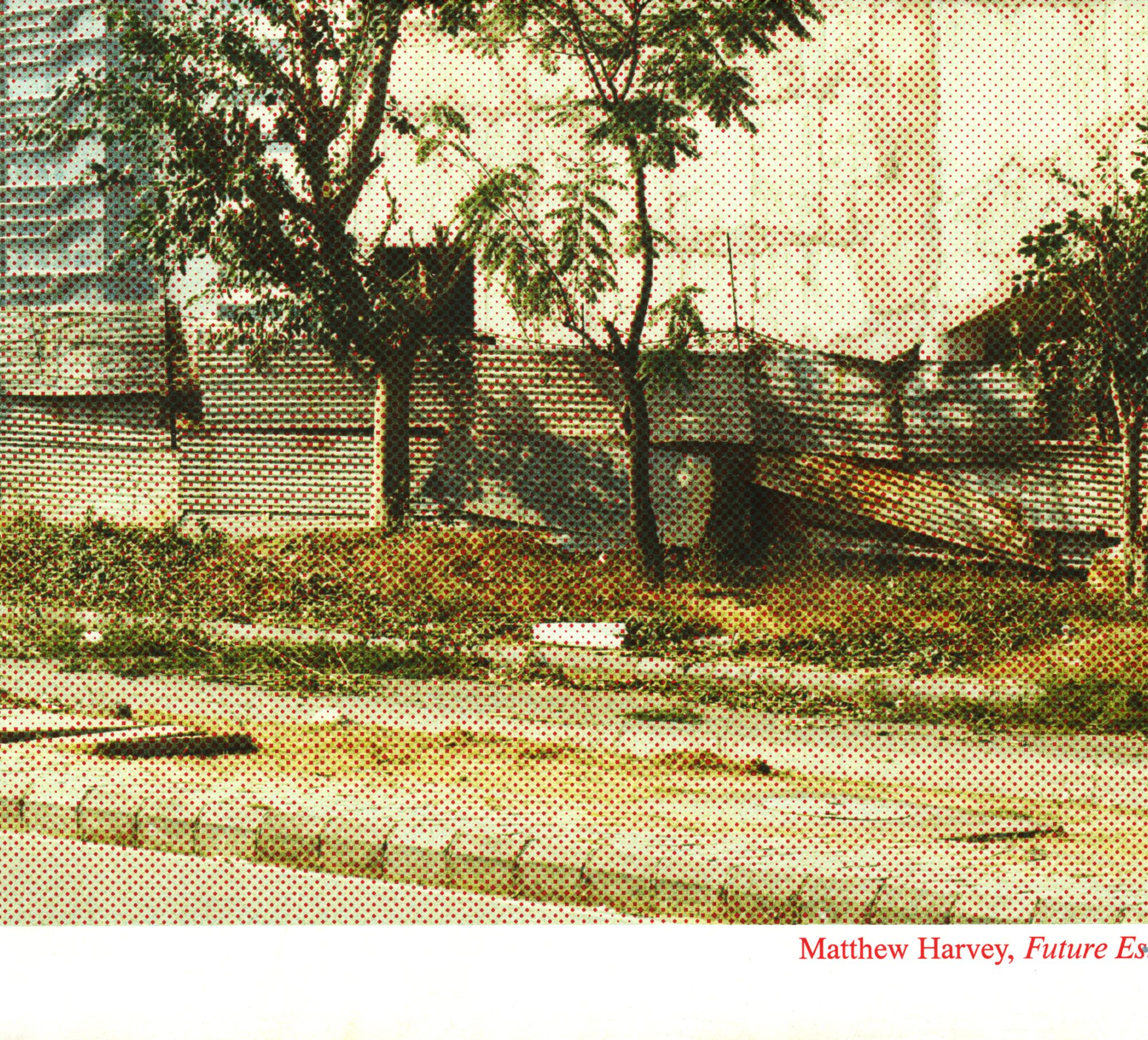

Matthew Harvey has compiled what I can only describe as a series of photographic observations regarding roughly what the global world looks like under the pressures of globalism and the incessant drive toward progress, itself a challenging subject matter. His photographs work in a manner similar to Lewis Baltz and other mem,bers of the New Topographics movement, popular over half a century prior, yet in Harvery’s photographs, analog and developed in each region he visited, the formalism of photography for the sake of composition and art dialogue is dropped for the sake of a strange acid-fried realism. The color palette from his images suggests, in places, a sulfuric or battery acid taste, the coppery or arsenic-sputum-like flavor of a destructive and unwanted elixir fixed at the wet corner of the jowl, directly proportionate to the activities hinted at in the photographs themselves.

Matthew Harvey has compiled what I can only describe as a series of photographic observations regarding roughly what the global world looks like under the pressures of globalism and the incessant drive toward progress, itself a challenging subject matter. His photographs work in a manner similar to Lewis Baltz and other mem,bers of the New Topographics movement, popular over half a century prior, yet in Harvery’s photographs, analog and developed in each region he visited, the formalism of photography for the sake of composition and art dialogue is dropped for the sake of a strange acid-fried realism. The color palette from his images suggests, in places, a sulfuric or battery acid taste, the coppery or arsenic-sputum-like flavor of a destructive and unwanted elixir fixed at the wet corner of the jowl, directly proportionate to the activities hinted at in the photographs themselves.

The analog processing of his photographs is an integral part of the discourse. With their chemical development and need for physicality, the analogue process reflects the world of globalism, technical destructive reliance, and medium-specificity tied to industrial capitalism. Although they could have been created digitally, that would not alter the cumulative corrosion of their execution. We tend to forget our complicity in the system of making images to discuss and disparage capitalism with little effort, and Matthew reminds us of our gifts to the pantheon of cancer alleyways in his pictures. He makes them self-referential through this exchange, not absolving himself, but instead honestly claiming his complicity in their production. The outcome is a type of industrial sublime, an overarching sensation that, even in the banality of their delivery, the atmosphere of overbuilding, the eruption of concrete, upward architecture, and infrastructure suggest something so vast and stretchjing as to be considered something above the comprehension of a single human, but instead, like an organism with unmitigated power suggests that the God in man has been let toose to rape and pillage the sleeping green eden-a collective rapacity misunderstaood by the sigular cell for its alarming appetit.

With anecdotal notes and an essay detailing Harvey’s background in Appalachia, the book presents a holistic view of the topic of expansive globalism and commodity production. His personal insight limits what might otherwise feel like an analytical gesture. The vernacular 35mm aesthetic choice maintains consistency throughout the years of shifting from analog to digital production, and his general lack of overproduction makes the book a sublime visual discourse on a meta-object of globalization and overproduction. Framing these concepts is challenging, but in the aggregate, Matthews’ book of images begins to make sense, and I believe it to be one of the more successful books to offer a discussion on those topics. It also feels like a smarter, less composition-driven (re: arty) update on New Topographics, suggesting that their battle with the landscape and humanity’s overbuilding and reckless pursuit of growth has failed. Highly Recommended.

Matthew Harvey

Future Estate

Roma