I know very little about Witold Gombrowicz, let alone Witold Gombrowicz’s book, Memoirs of a Time of Immaturity. Still, upon reviewing his biography, one can’t help but find him a fascinating character. One part Jean Genet, one part Jean-Paul Sartre, Gombrowicz’s work seems to embody the twentieth century’s anxieties, both in terms of the Holocaust and war, as well as the era’s immersive exploration of identity in a world of burgeoning globalism. He lived in Paris for a short time, rubbing elbows with the intellectuals, which no doubt informed his interest in pursuing a creative life. Gombrowicz left for Argentina by boat slightly before the war on the continent started. Having received news of the battle unfolding, he remained exiled in Argentina until 1963, before returning to Europe and passing away in 1969.

During his lifetime, he wrote numerous short works of autobiographical fiction and nonfiction, exploring his life and interests in Buenos Aires, as well as his time in Europe before and after exile. Many of the short stories were combined into several books, notably Bacacay, or Memoirs from the Time of Immaturity, first published in 1933 and then reissued as Bakakaj or Bacacay. This book of short stories is a direct repudiation of his interest in the long form of the novel, and the stories revolve around several different characters and their navigation of social and cultural life, with an emphasis on the psychological pragmatism of interpersonal relationships. Often existential and tense, the stories convey a sense of playful and comedic absurdism that disrupts the sharp edge of European existential thought, as reflected in several post-structuralist writings and the thought of the mid-century period.

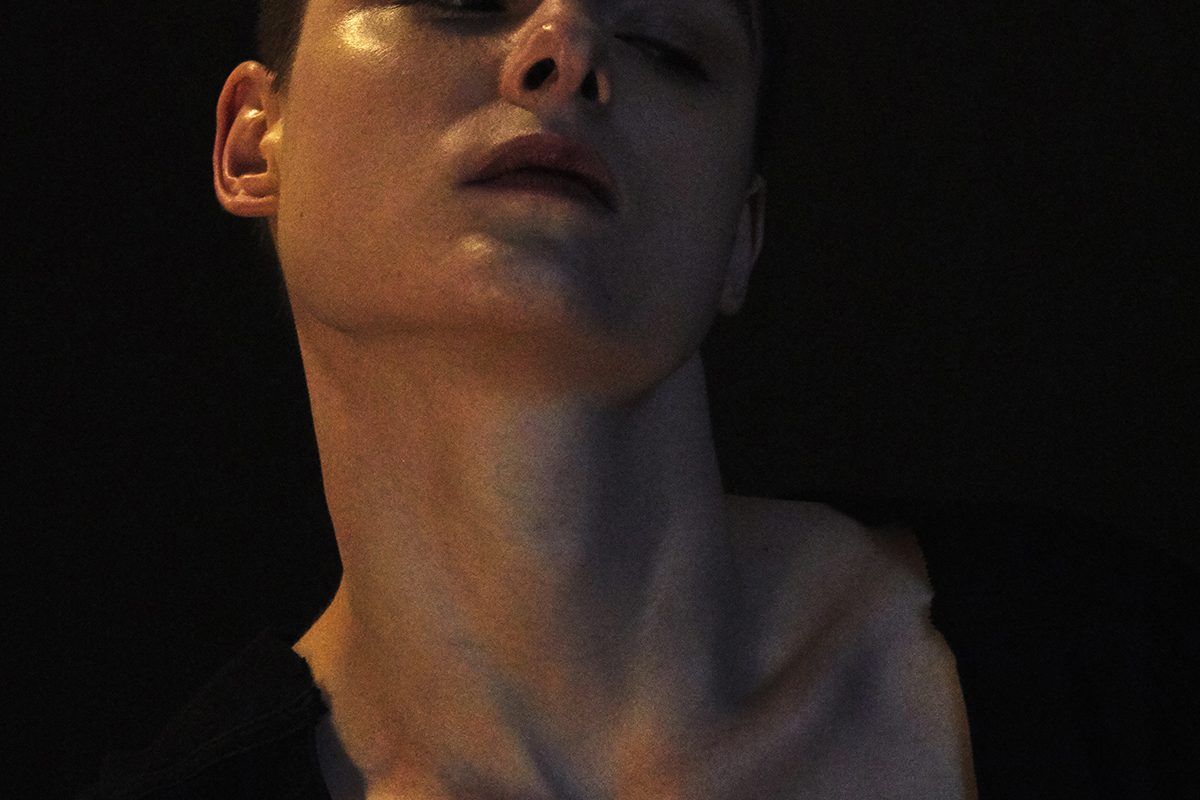

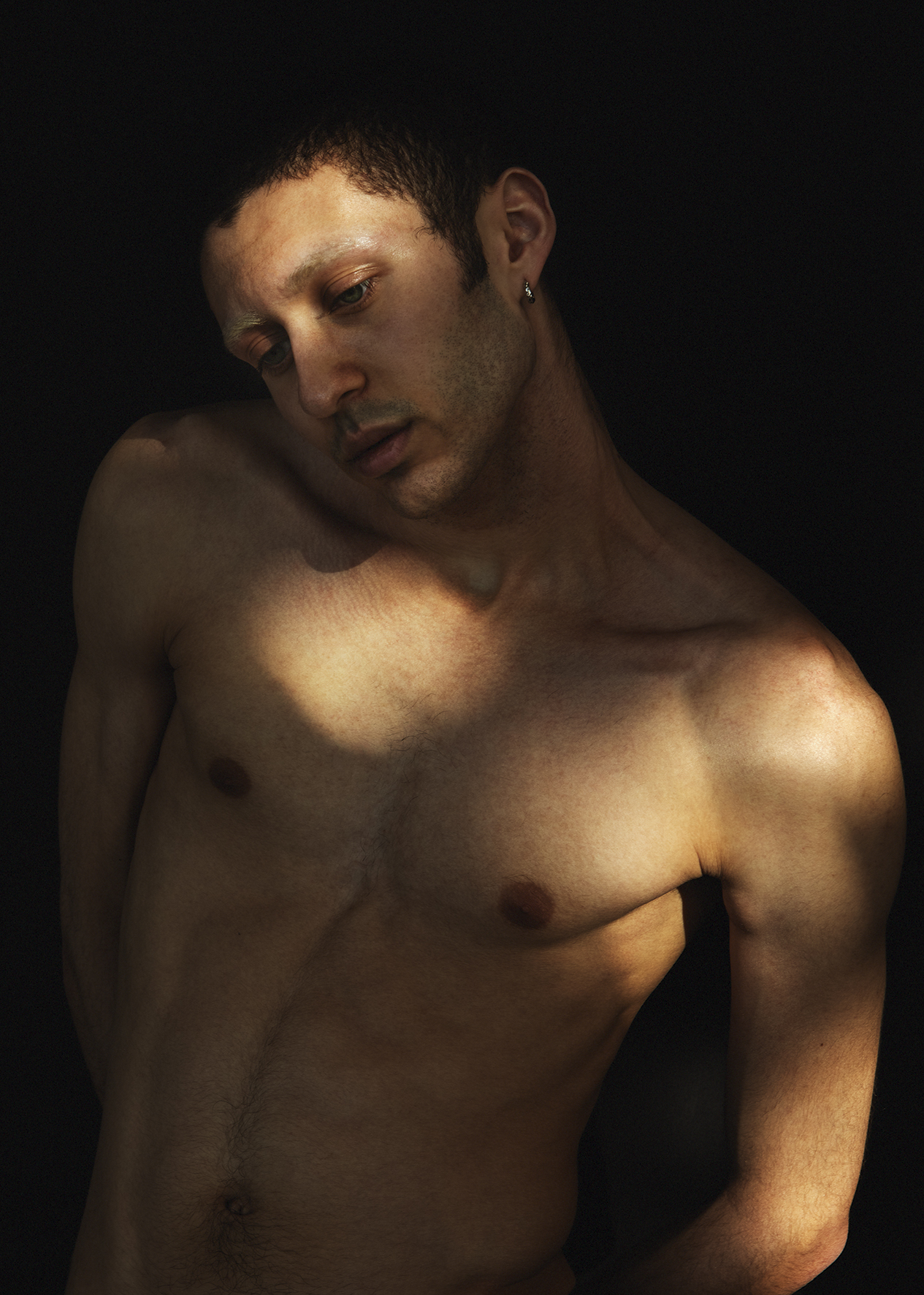

These stories and Gombrowicz’s life are the inspiration for Nolwenn Brod’s photographic journey through the travels, exiles, and steps of the Polish Author. The French photographer has created a convincing and cinematic tie to Gombrowicz’s series of short stories through her images. She has followed his path from his native Poland to her native France, with an excursion to Argentina. The pictures she brought back are like distilled twilight; their brooding and crepuscular forms are fleeting and ephemeral, emerging and receding into shadows, hinting at expressionist film stills. The images present as intimate, yet there are moments of anxiety or anguish; lost screams reverberate through apartment blocks, and looming shadows suggest a place of stasis —a limbo of sorts in which things are frozen in amber light. Bodies stretch, mouths are pulled apart by the exasperated bellows working from inside the body, pumping distorted air through the funnel of lips—Edvard Munch, the boy who lives inside my mouth, fighting against the contractions of its clasping purse, unable to stifle its escape: possession, Adjani, spilt milk, harrowing and alien miscariages of fortune. Everything here looks like a glove with small shards of broken glass lining its interior-an excision with scarring potential.

I am reminded of Michael Ackerman and Alisa Resnik in many ways through Brod’s work, particularly the latter’s On the Night That We Leave, also published by Lamaindonne. However, I believe others might see an influence of Antoine D’Agata. I prefer to err on the side of Ackerman, whose narrative and empathetic values I find more in line with the subject matter of Brod’s interests, as well as her handling of portraiture. A heavy dose of modernist framing of the face and body is also evident here, and it would not surprise me if the artist were influenced by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Lucia Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, or Man Ray, considering Lee Miller’s neck as a reference point. I believe Brod has been conjured from a different twentieth-century life, a rebirth perhaps, starting in the 30s, traveling through the European post-war 70s.

There is a penchant here for heavy doses of bohemian romanticism that fits within those 40 years, including the melancholy of artists like Christer Strömholm and early Ed van der Elsken (Only the business of the Left Bank). At a stretch, the odd, disjointedness of Chris Marker, who explores the future, the past, and the present, is lost in a state of being. Rainer Werner Fassbinder also feels like a logical extension, and by that extension, Gundula Schulze Eldowy. The digital grain and dissolve expand in low light, producing in Brod’s work these links to the past, to the ephemeral ghosts of imagination tied to the sinking rock of expectation. We are given half-truth, half-light, and half-people culled from some obscure angle or vantage point, an eavesdropping on what or whom haunts us—highly recommended.

Nolwenn Brod

Le Temps de l’Immaturité

Lamaindonne