The cyanotype is a very flexible process developed from water. One paints or layers ferric ammonium oxalate and potassium ferricyanide on a substrate, usually paper, but also fabric. One then exposes a negative or an object to direct sunlight. After a test has been made, the print is washed in water, revealing a beautiful Prussian blue image of the positive (from the negative) or a negative shape of an object left on the paper. It is an oddly satisfying and fun process, and in the days of analog, even in my youth, educators used it to inspire children to make photograms. Due to its simplicity, the process has survived, and you can still find people working with it.

Throughout history, these objects have often been associated with herbaria and plant studies, as seen in the work of Anna Atkins in the mid-19th Century, or with architectural drawings used to make multiple copies of an architect’s plans. Invented by Sir John Herschel, a family friend of Atkins, the cyanotype is a widely used, mostly stable photographic process. By the twentieth century, postcards, pillowcases, dresses, and the continuation of architectural plans made the process increasingly ubiquitous. You also find cyanotype used on early-20th-century postcards. The idea of communication, picture, and exchange made it a quick and relatively painless process that could be done at home, with family negatives, etc.

During the 90s, there was a resurgence of alternative methods such as cyanotype, salt printing, and collodion negative-making. It was a somewhat niche area with artists like Dan Estabrook, Jayne Hinds Bidaut, and, most notably, Sally Mann, making these processes popular again. A little before that, Francesca Woodman also similarly made Azo prints, and a little before that, Floris Neüsuss made similar photograms of the body, but on silver print paper. There has been a slight decline in their interest; both cyanotypes and photograms remain part of the landscape of photography and a beautiful way to express ideas, though indebted to a specific past aesthetic.

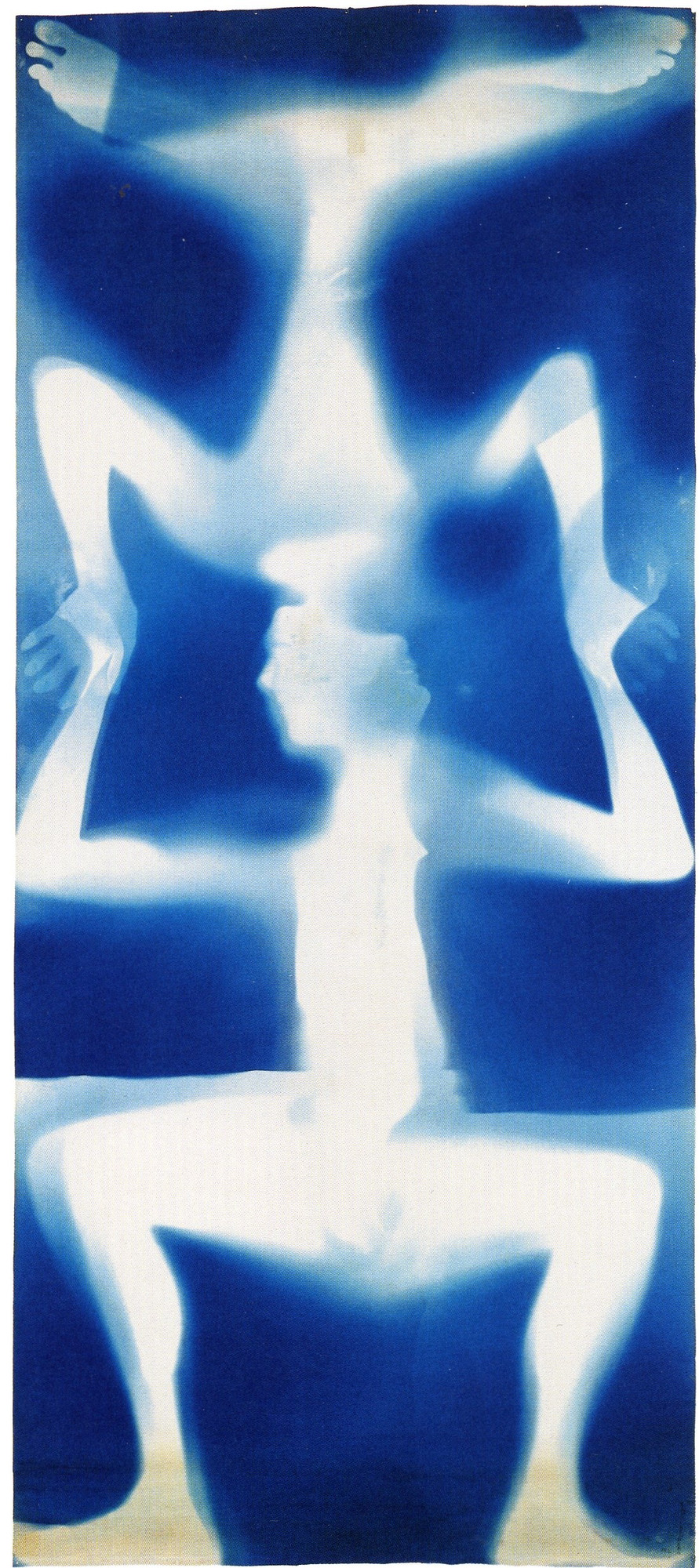

Concerning the process and its use with Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, his former partner and the mother of his child, the pair began their interest, however short-lived, with the cyanotype in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The couple produced several life-size prints of both Rauschenberg and Weil as bodily photograms on large coated paper and cloth, giving their bodies a reluctant, haunting visage laid out on the sheet, with other objects added. The beginning of the process must be directed toward Weil, whose family had a long history of the process through architecture. Through the interview with Lou Stoppard, we learn that Weil’s great-grandfather was none other than architect Dankmar Adler, whose firm in Chicago was a significant figure and collaborated with none other than Louis Sullivan.

In short, Weil’s experience growing up led to her and Rauschenberg’s creative experimentation in the early 50s, which is the subject of the book. Weil is often overshadowed in this work, primarily because of Rauschenberg’s significant shadow, but also, in considerable measure, because of the times in which work like this was produced and particular attitudes toward women in the arts. Her work is extensive, and she is still, at the age of 95, a lifelong artist, which speaks to the power of art and the consistency it asks of us throughout our lives. You are a lifer or not, and she should be acknowledged as such within the context of this early body of work with the late Rauschenberg.

Weil studied at Black Mountain College under Albers and was no slouch in the world of art-making. Her pedigree and obvious talent isa due for a larger, more rounded re-examination, but regarding, for the moment, the contents of this book, it is with great pleasure that we se the work smartly assembled in one volume with equal emphasis placed on both artist and particularly Weil’s word in the intervew with Stoppard which goes along way to explain her process and position int he making of the photograms, but also her position in New York, during the 50s and 60s concerning the problems regarding female visibility in the arts. An activist, Weil was an essential catalyst for Rauschenberg at an early stage of his career.

Though much emphasis has been placed on the latter’s relationship to Twombly and Johns, I think it is fair to say that, from what can be culled from the interview, Weil’s seed of interest in the cyanotype significantly shaped Rauschenberg’s thinking about production through their collaboration. In this regard, she deserves this volume of work as a co-artist to set the record straight in line with the production’s reality.

For me, what really resonates about this book is two-fold. First, I love the tactility of its production. The craft paper and the blue cloth reveal the materiality of the cyanotype process in hand, reminding me of the work’s physicality. Second to that, I love that it is a small volume of pictures, but that, toward the end, the emphasis is on behind-the-scenes shots of the process of making the work itself. I love seeing artists create work, so this makes for a special volume for me, and I am not even a huge Rauschenberg fan, but I welcome the introduction to Weil and their collaboration. This is the type of book that extends from a casual photobook into a vital record of a specific and critical moment in history, thus illuminating it for a more monumental reception, and will, of course, be essential for Rauschenberg and Weill fans as well as institutions.

The publisher has had a couple of really brilliant hits over the past year, with this title, the new Arthur Tress book, and Nikolay Bakharev’s book all published over the past few months. I am a sucker for this simple type of elegance in which the materiality of subject matter is matched, without overpronunciation, by the tactility of the book object. What Stanley/Barker does incredibly well is keep the books focused on the work itself through uncomplicated design and a beatable sequence of images. The restraint shown is what makes their books easy to communicate the work, not the designer or the publisher, as is the case in many publishing houses at present. Their books tend to become classics and are expensive to re-encounter, which is a good marker of their quality. This book also escapes the narrow world of photography and bridges the divide between a crucial set of voices in a particularly essential period of American art. Now if only we could get a decent Cy Twombly photography book of photographs.

Robert Rauschenberg & Susan Weil

The Blueprints, 1950

Stanley/Barker