*not pictured

*not pictured

My version of this film begins with the establishing shot in the same manner as Désirée’s. I pan over downtown Los Angeles. I try to skip the normative sunset, smog-ambitious, clichéd photographs of the city. I am not focusing on anything in particular. I am not overly concerned with landmarks, not interested in anything completely recognizable. I think of how I can position myself in the city in the broadest sense. I almost want it to look like any ci.ty. Then it clicks. I do not crane my neck. I do not even squit. Within the broad fabric/tapestry/built ritual of concrete tumbling slower than molasses over time, molecular shifting downward like the glass held too long in window panes, I see it.

I try to tignor it at first, more interested in panning over the city under blue skies, destabilized from my later camerawork on the ground, which will be shrouded in a cavernous series of overshadowed executions, with craned neck, looking up, running parallels down the length of a street zooming in looking for details, corrupting language through a series of textual dissections, leveraging building signs into new forms of type, asking, reading, waiting for a message sent from the perspiring bottle of the city’s origami,

I try to tignor it at first, more interested in panning over the city under blue skies, destabilized from my later camerawork on the ground, which will be shrouded in a cavernous series of overshadowed executions, with craned neck, looking up, running parallels down the length of a street zooming in looking for details, corrupting language through a series of textual dissections, leveraging building signs into new forms of type, asking, reading, waiting for a message sent from the perspiring bottle of the city’s origami,

*pictured

I cannot ignore the broadside advertisement painted on brick as it triggers too many cultural memories-recollections that are not mine, but are embedded in my knowledge of this city. It hints at everything and nothing at all. It is only a sign for accommodation, yet it sighs a bellowing, fetid breath over everything I associate with this bizarre patchwork of a place. It heaves a sigh toward oil derricks, Jack Parson’s inept fingers (maybe), and a woman found in a lot in 1947. It reminds me of other hotels, ones in which a hopeful man lies bleeding out on the kitchen floor. It reminds me of all the allegations. It reminds me of all the ways, in its present state, it is becoming a broadening tent city, reminiscent of a film by John Carpenter. If only I had bubble gum or sunglasses. Bunker Hill, dancing in misery.

*still not pictured

In terms of establishing shit, my shot, as it were, is pointed at an anxious building. Its anxious state comes from its historical marker of a disappearance. Painted alongside the wall, Cecil. Beaton? B. Demille!

*not pictured

I venture outside, thinking about the cultural signifiers of LA rooftop water tanks, distinct from New York’s Water tanks for the invisible packaging they contain, water-logged black hair, jump scares, and invisible elevator rides into cryptic endings. How do we end up here? Los Angeles continues to stoke my imagination as I pass through its skidrow enclave, needles crunching underfoot, bubble gum black tar, and the unhoused, no longer homeless, I guess, make tracks along arms and sidewalks. The soft underbelly is still making good grift off tragedy, despite claims to the contrary. It doesn’t matter, the sickness is rampant and its spectacle is seen much further past the limits of the hills, vacuously corrupting a nation hell bent on parking lot ballads. Get fucked, Mark.

*certainly not pictured

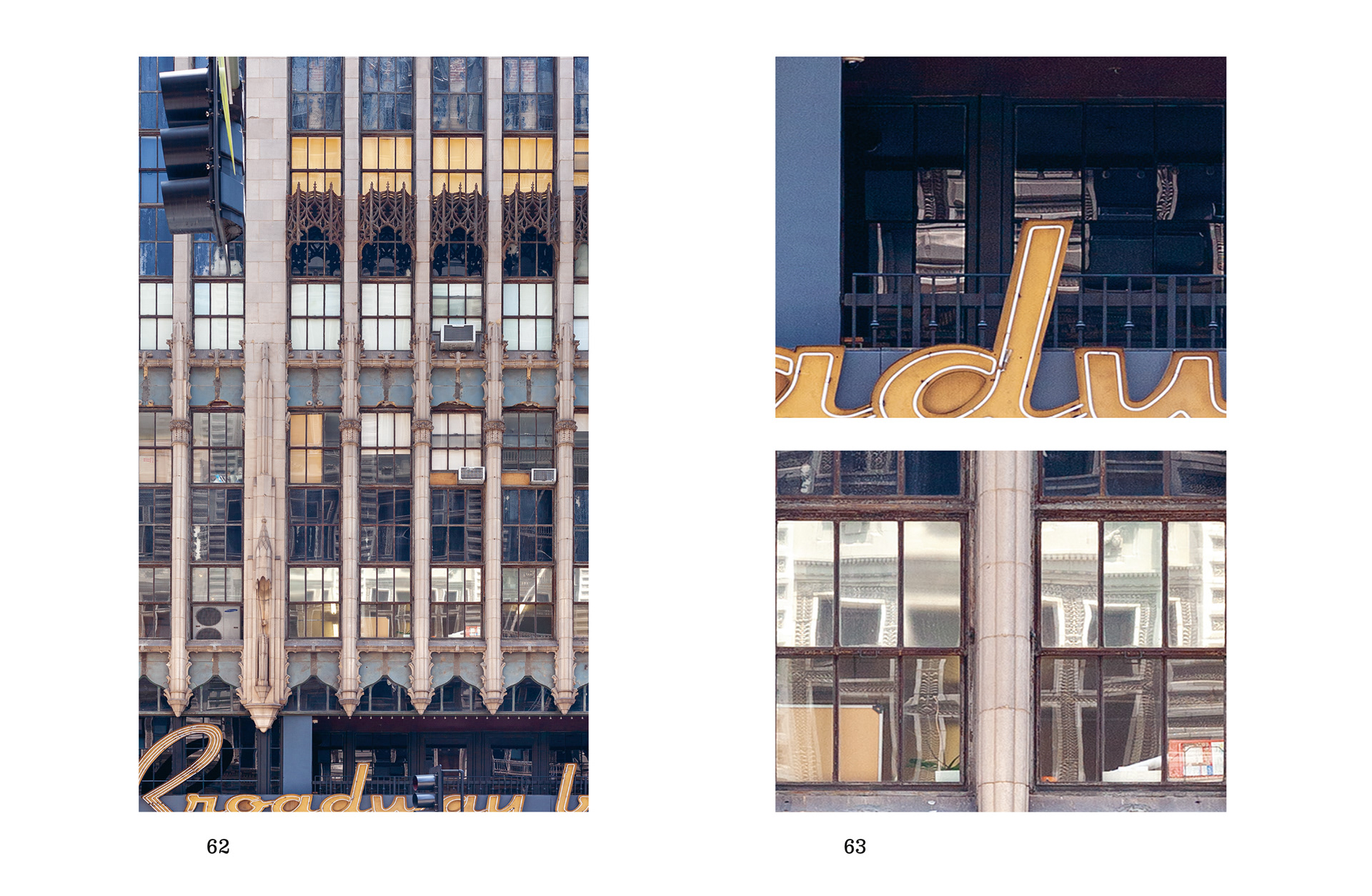

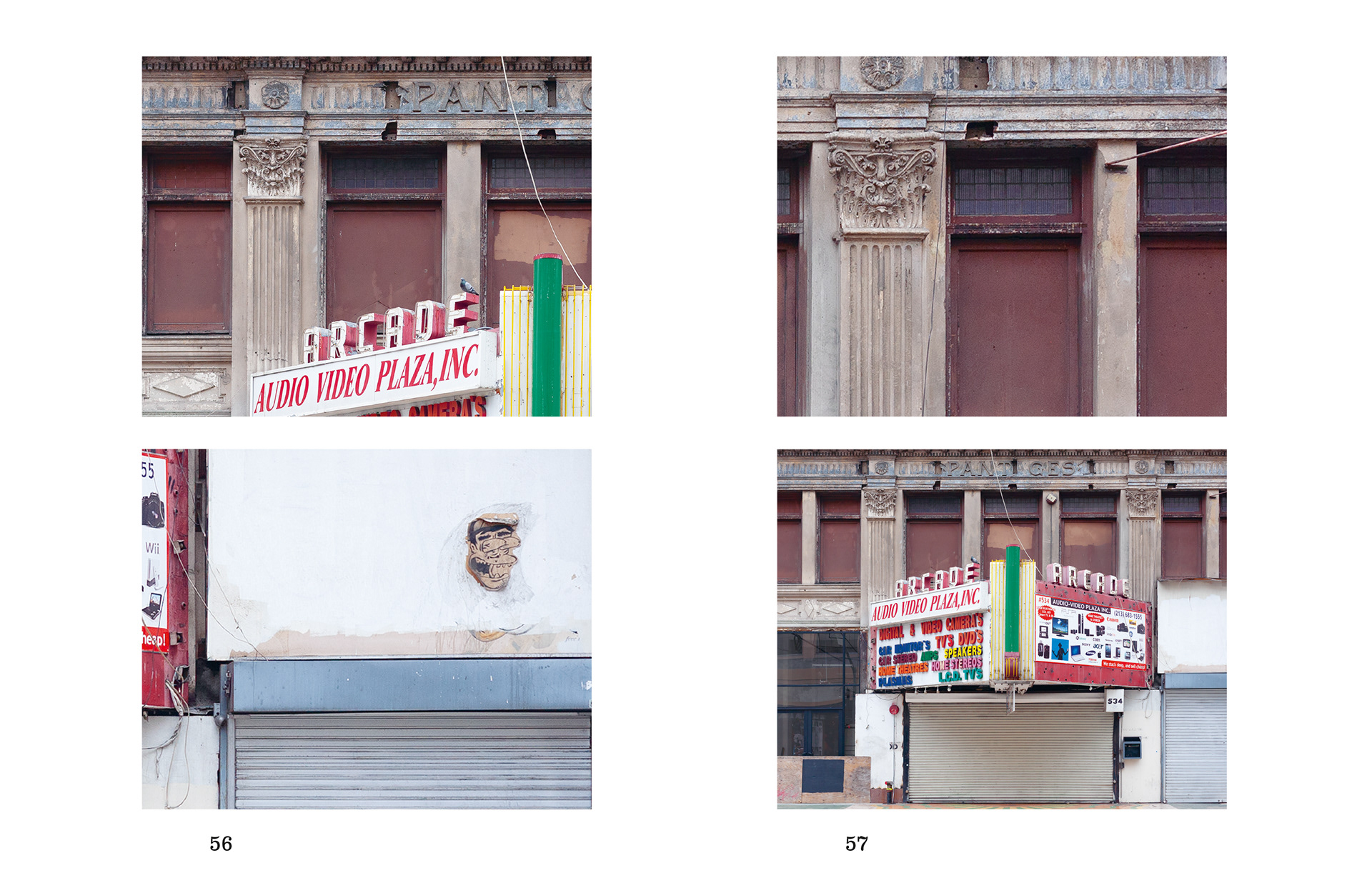

I continue, along with my imaginary date Désirée. Similarly, the typeface of the buildings’ rusted signs downtown points to former glory, and it is hard to ignore their geometry. Whereas I am content to keep my vision mostly along the horizon, Désirée shoots upward and inward, clicking along broad views before zooming in. I watch fastidiously as the camera lens extends and retracts. I think of the lettering and the details and how they will be presented in form. I am curious as she snaps away what will become. I imagine long sentences running through a book, fashioned through a large amount of letters culled from different signs, a ransom letter written out in ink on a page. I am reminded of Lee Friedlander, as well as Jack Pierson, both of whom have utilized type to significant effect in their books and exhibitions, salvaging these letters and messages from the peepholes of cityscapes, from yonder times. I am also encouraged to think of John Gutman, but it’s not quite the proper city.

*pictured

*pictured

All of this looking, observing, cutting in, is phenomenally interesting. In person, the act or ritual of acquiring these photographs is not particularly interesting to watch. There is no big setup. There is no tripod or overexaggeration of photographic performance. You would not know we were here if there were no mythology of the city fulfilled in the recording of it all.

This is the third book in Désirée van Hoek’s series of notes on Los Angeles and its downtown. It is the smallest book in terms of size. It is accompanied in great detail by Norman M. Klein and his sprawling love letter to L.A. What I find incredibly appealing about this third book is that it comes at a time when L.A. prepares for a seismic shift away from the problems that plague it in the Skid Row and Downtown area at large as it prepares for the 2028 Olympics. It is a paralyzing moment that comes after the rather significant shift toward homelessness and an opioid plague that has permeated its confines. I don’t think I am the only one (from afar, mind you) to notice the grave issues plaguing the city. I am concerned for the people who will be scattered to the winds, likely not getting the help that they need, as a show of face for international sports tourism. Désirée van Hoek’s work is crucial at this time. Although it is not meant to be a document, I believe she is capturing the last vestiges of what we think of when we think of downtown Los Angeles, whether that is for better or worse on the sociological scale.

Her camera work has also changed. Her pacing and focus have become more cinematic, more punitive in their details of decay and structural weathering. She is playing with the details by zooming in at points in a three-point perspective laid out over a double-page spread, and this is fascinating as it lets us dissect the single broad image into its parts and asks us to understand images, not unlike how Christian Marclay dissects time through the cinema in his piece The Clock, from 2010. The cuts are crucial to thinking more myopically about material, as well as the passage of time. Klein’s essay culturally outlines this, chopping and cutting to different ways in which we imagine the city, but mainly through an anti-realism, and more in line with the dream machine or mythology of the place, which is offset by the photographs in the book with their scrutinized look at the material/architectural condition of downtown Los Angeles. It might be my favorite book of the trilogy as it, in its diminutive form, offers a fresh take on the city, much in the way that the work of Anthony Hernandez also suggests an alternate way of seeing the city. Highly Recommended.

Her camera work has also changed. Her pacing and focus have become more cinematic, more punitive in their details of decay and structural weathering. She is playing with the details by zooming in at points in a three-point perspective laid out over a double-page spread, and this is fascinating as it lets us dissect the single broad image into its parts and asks us to understand images, not unlike how Christian Marclay dissects time through the cinema in his piece The Clock, from 2010. The cuts are crucial to thinking more myopically about material, as well as the passage of time. Klein’s essay culturally outlines this, chopping and cutting to different ways in which we imagine the city, but mainly through an anti-realism, and more in line with the dream machine or mythology of the place, which is offset by the photographs in the book with their scrutinized look at the material/architectural condition of downtown Los Angeles. It might be my favorite book of the trilogy as it, in its diminutive form, offers a fresh take on the city, much in the way that the work of Anthony Hernandez also suggests an alternate way of seeing the city. Highly Recommended.

Désirée van Hoek

Talking About L.A.

Self-Published