While reviewing my work over the past few days, I have begun to realize the essential nature of architecture in my oeuvre, as well as in contemporary photography in general terms. I think most of this is due to its observable primacy in our environments. Buildings, structures, and other habitable (and inhabitable) objects reign over our daily lives. Some of these objects are intolerable, designed to effront the human tendency for wandering, denying the desire of our journey, demanding that they be adored through observation. Others are complementary to our existence and suggest a cohabitation, for I might speculate that once an architectural object has been completed/produced, it is no longer indebted to the builder or the human perspicacity of human desire.

These objects arguably live and must be thought of, however immobile as entities, if not sentinels. Their embodiment in the landscape is greater in scale than those envisioned in their construction. They are, at their root, comprised of ventilation (lungs), stairways and elevators (arteries and veins), and a core system of heating that pumps life through their ventricated compartments (heart). All are clad in varying forms of skin, some rough, some sleek and hairless. By anthropcentrisizing the experience of architectural objects, I seek not to wrest them from their form or genesis, but to equate them to the denizens who observe them in a strange reciprocity. Architectural objects, if thinking were something we believed them to do, would likely have a much different, perhaps parasitic condition for which to consider humans.

Architecture is exposed to life. If its body is sensitive enough, it can assume a quality that bears witness to past life.-Peter Zumthor.

Regarding architectural objects and their animated potential, I am drawn to their position as sentinental observers of human activity, no matter their inability to speak directly back to us. They are consummate testaments to the fires and choking exhaust that labor before and beneath them, often taking on their environmental conditions, with pockmarked holes left in their skin, a loose, corrosive, acidic bath coarsening their skin from eras of chemical ambiance. Their arteries, steps, worn from the tread of human feet, bear the slow, syrupy slide into stone waves, as evidenced by Frederick Evans’ famous photograph, ‘A Sea of Steps’ (1903), from Wells Cathedral. The body of the architectural object is not immune to either history or decay, creating a further synergous analogy to the body of humankind. Human bodies also bear the scars and decay of history, malnutrition, and bones sawed apart to be examined, just as tree rings reveal the passage of time. Healed fractures of broken arms, a hint at the navigation of time.

When I think of images of architectural objects, I think of them as portraits, or as interior observations from within, nearly surgical in their execution. I might argue that the interior viewing of these objects is invasive to their bodies, depending on the level of scrutiny and outcome. In examining their corpus for internal malady, these observations are akin to a trip to the doctor, or more succinctly, as though a house doctor or technician has come calling to diagnose the malady present, including leaking roofs, shifts in the internal structure, sinking corners, and unwanted carcinogenic rot. I believe it is challenging to use the term ‘objective’ when dealing with such subject matter. When discussing architectural photography, no matter how analytical it may be, the author’s condition, including their reading, feelings, and perception of the space, both internal and external, is evident. This leads me to an understanding of attempts at architectural photography as subjective, as a divinely combined product of the body of the architectural object and the creator/observer who produces images of its bulk.

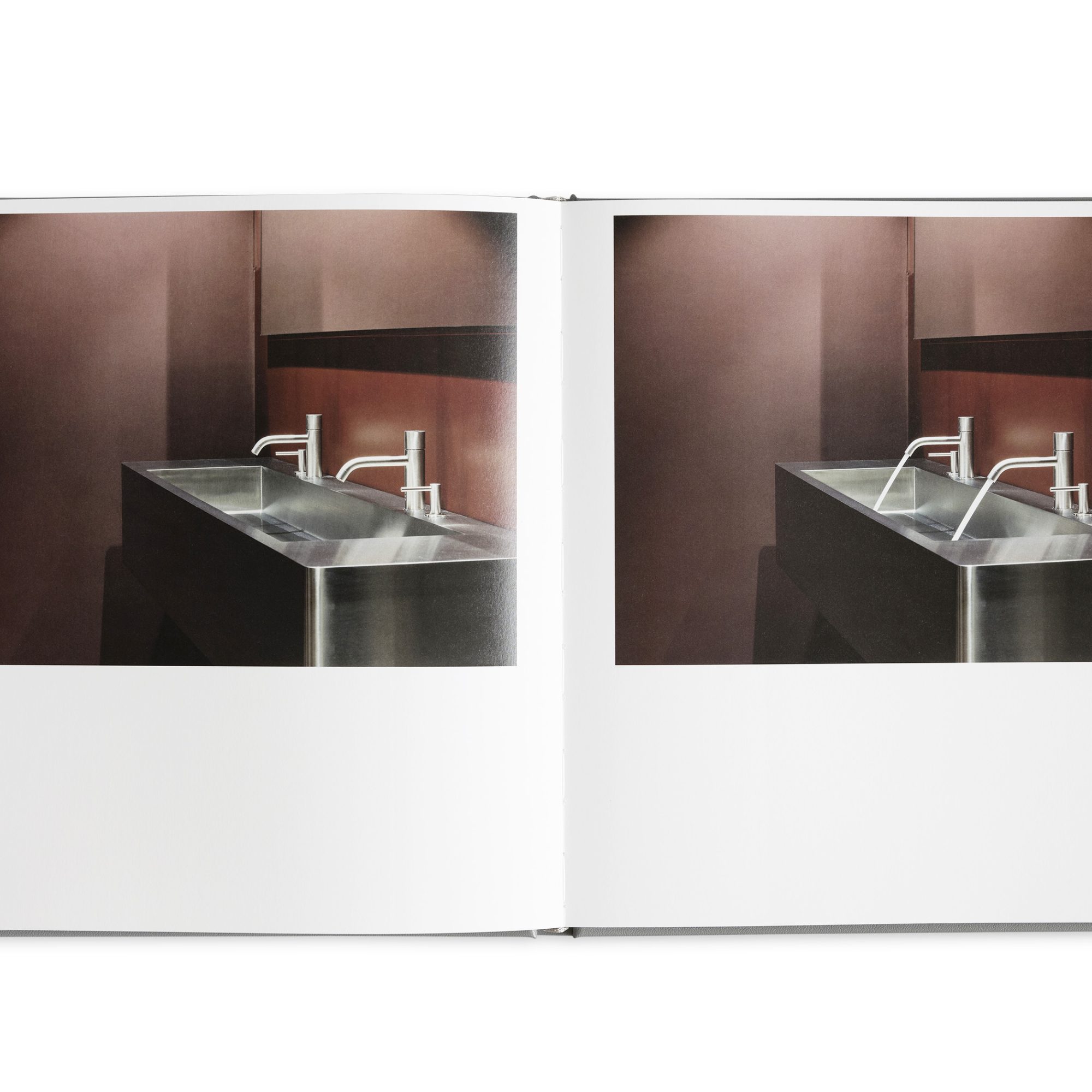

Andreas Gehrke has been focused on architecture for the past 15 years. His books have demonstrated a clear consistency, both in subject matter and in execution. Although they appear as minimalist interventions in space, there are significant clues that the images are Gehrke’s. One is his use of light. He has developed a way of photographing buildings with compositionally calculated natural light. Shadows rib the floors of clean and sanitized space. His photographic detailing of surfaces exhibits a strong and often undervalued sense of color palette, frequently using silver and deep, profound reds to convey an emotional register to what would otherwise be deemed abstraction without cause.

Andreas Gehrke has been focused on architecture for the past 15 years. His books have demonstrated a clear consistency, both in subject matter and in execution. Although they appear as minimalist interventions in space, there are significant clues that the images are Gehrke’s. One is his use of light. He has developed a way of photographing buildings with compositionally calculated natural light. Shadows rib the floors of clean and sanitized space. His photographic detailing of surfaces exhibits a strong and often undervalued sense of color palette, frequently using silver and deep, profound reds to convey an emotional register to what would otherwise be deemed abstraction without cause.

They are constructivist without feeling like a pastiche. More recent uses of doubling of similar images, much like work seen by Guido Guidi, add new elements to the process, which limit the work from being functional to the objective aims of documentation. In a world of architectural photography that emphasizes the single image, this is refreshing and adds a subjective pathos, along with Gehrke’s formal compositions and color, to an enduring artistic output bereft of simple function. Whereas these architectural objects bear significant personality and subjective form from the architects, it is Gehrke who transforms them, as the architect does material, into value.

The building in question for this book, elegantly designed by Marek Polewski (the second for Gehrke, following Flughafen, 2023), is located on Müllerstrasse in Zurich, Switzerland. This building has been repurposed by Ilmer Thies Architects, whose firm reinvents existing architectural objects, bringing them up to current ecological standards while also preserving elements of their past architectural identity. Instead of scrapping all remnants of their past, the architects emphasize remodeling and using what is integral to the structure, with some of its detailing to upscale the buildings for the contemporary moment. This is not easy work. One must work with the existing structure and materiality of the object to ensure code, but also to maintain a sympathetic connection to its past, when it may be less challenging to start over and let the architect’s ego take over with new prospects.

]In working on the space with the architects, Gehrke has been given access to the object and has made a compelling book of photographs that is in direct service to the project. In places, I am reminded of Thomas Demand, for the static images that almost appear unreal due to their cleanliness and perfection. The double view of the sink with the water running on and off certainly embraces this feeling, as do some of the images of the building’s exterior, which almost, but not quite, suggest an architectural model.

There is a fracture in understanding the photographs between the world of the scaled, the imagined, and the observed, which confounds and enigmatically renders the viewer’s assumptions about architecture false, leading them to the subjective experience of the author. With the essay and diagrams at the back of the book, it pulls us back into the realities of architecture. Still, it concludes as symptomatic of a total breach of its objective intentions, giving the viewer insight while also providing space to project, making the experience both enjoyable and informative. This is Gehrke’s finest work to date.

ITA Müllerstrasse, Zürich, 2023

Andreas Gehrke and Ilmer Thies Architects

TOTALSANIERUNG

Drittel books