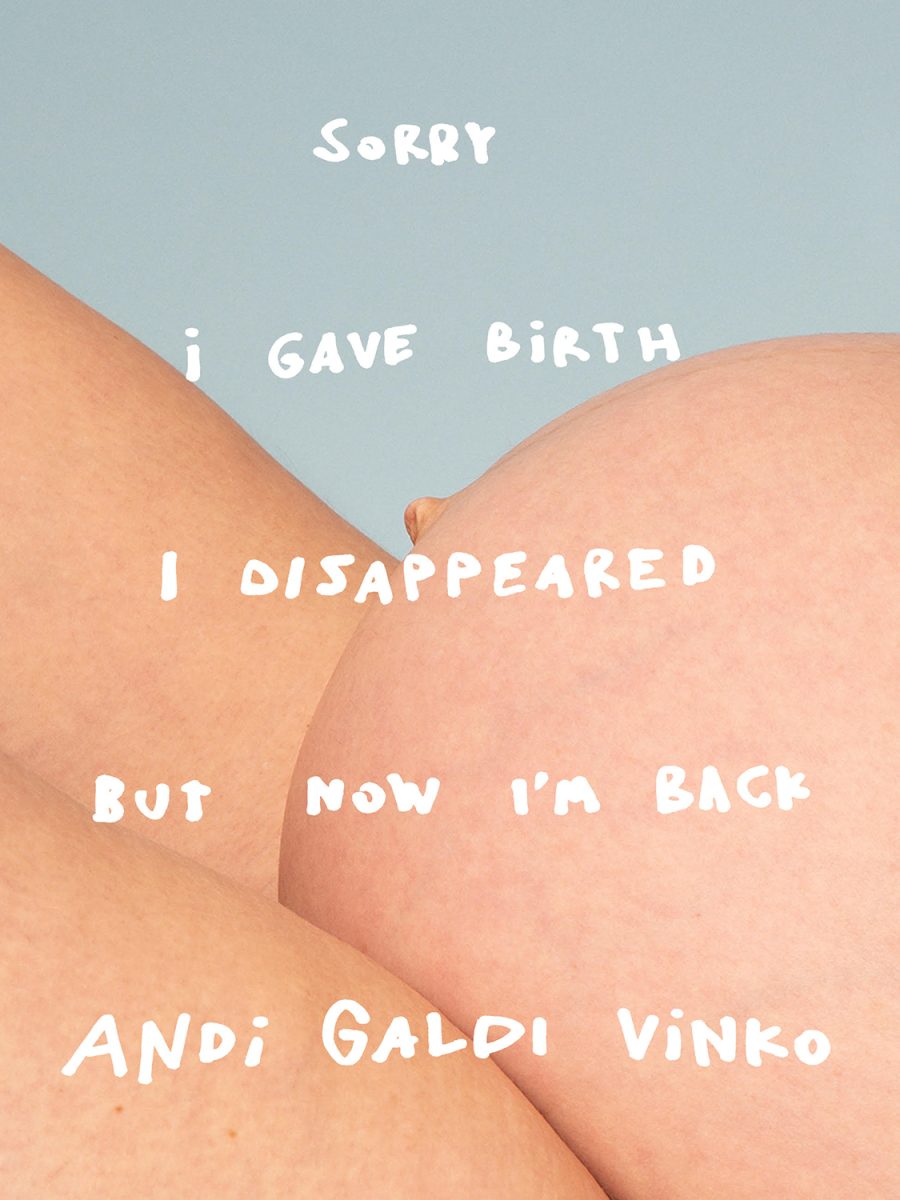

Artist-photographer Andi Gáldi Vinkó turns her lens on the raw, often overlooked facets of pregnancy and early motherhood. In this interview, she discusses her photobook Sorry I Gave Birth I Disappeared But Now I’m Back and explains how her candid — sometimes subversive — images dismantle stereotypes while illuminating the everyday experiences and unspoken struggles of maternal life.

Marika Tsouderou (ASX): As I was reading about your project, I paused at what you said—that you were brushing your hair, losing a lot of it, and then took a photo of the hairbrush. Was it that very hairbrush with your hair on it that inspired you to create this project?

Andi Galdi Vinko: The hairbrush was a starting point, at least in helping me realize how much remains unsaid about the early stages of raising a child. In the past, when families lived closer together, you could observe how others experienced postpartum life, which made things feel easier. Today, however, we are much more isolated.

What happened to me is a good example of what happens to many: you’re in your little universe, thinking everything is only happening to you. Then someone told me about a Facebook group for mothers. I don’t use Facebook, but I joined and asked, “Why is this happening to me?”.

Immediately, I got around a hundred answers from women worldwide saying it was normal. That’s when I realized how much of motherhood and the postpartum period remains invisible; stories that need to be told and seen. And so, this is my hairbrush, my hair, and my starting point.

ASX: You photographed yourself and your friends for this project for six years, first as a pregnant woman and later as a new mother. If I’m not mistaken, this was your first pregnancy. How did your husband handle the photography process?

AGV: My first daughter was born in 2017, so I started photographing in 2016 when I realized I was pregnant. In 2020, I had my second child. It began as something personal but soon included my friends. I had friends with kids before, but until I had my own, I didn’t fully grasp the difficulties.

My husband was very supportive and even helped with some images. If I had an idea for a shot I couldn’t take, he assisted. To this day, we joke—whenever one of those photographs sells, he says, “That’s my photo!”.

The process felt fluid. As always, the camera helped me capture and understand a phase in my life. What struck me most was that this project didn’t just help me—it helped others, too. Many reached out, knowing I was working on motherhood, wanting to share their experiences and contribute to the conversation.

ASX: You have said, “Because when you work, you feel like you should be with your child, but when you are with your child, you want to work” and “I love being a mother. I also loved being an artist”. Ultimately, you did both—being a new mother while simultaneously creating art about motherhood. Is that how you see it as well?

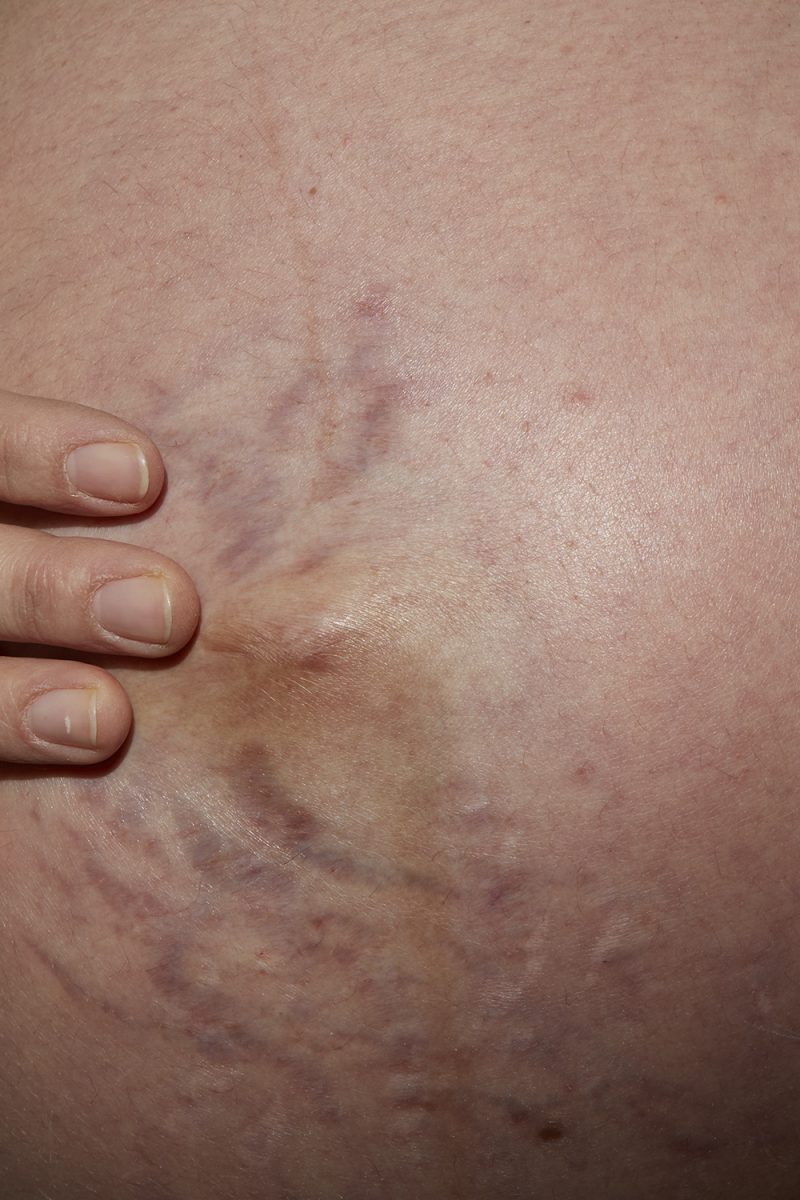

AGV: That’s a good question because many people ask me, “How did you make it?”, but I don’t think I was consciously creating art at the time. I had a list in my head of things I wanted to show because these experiences felt invisible. I remember searching online: “What does a sore nipple look like? How much hair do you lose? What does a C-section look like?”. But all the images I found were either overly medical or symbolic, hiding behind myths and taboos. That’s when it struck me—this hadn’t been represented in art. But I didn’t realize I was creating art myself.

Now, many artist mothers ask me, “How did you do it?”. In a way, I’ve become a reference point, which I never expected. Because, in the end, I’m still struggling just like they are.

My kids are now four and almost eight, but I still juggle decisions: “Should I take this job? It means leaving for a week. Can I?”. Even if I can, I still wonder, “What will I miss? What will happen while I’m gone?”. I might take a month off, and that’s when a big job opportunity appears. And I’m just like, “Why now?”.

ASX: Your photographic work Homesickland, although it deals with something personal—your homeland, your Hungary—features photos taken outside on the streets. This time, you are turning the camera inward, to your home and family. Did you feel exposed at all?

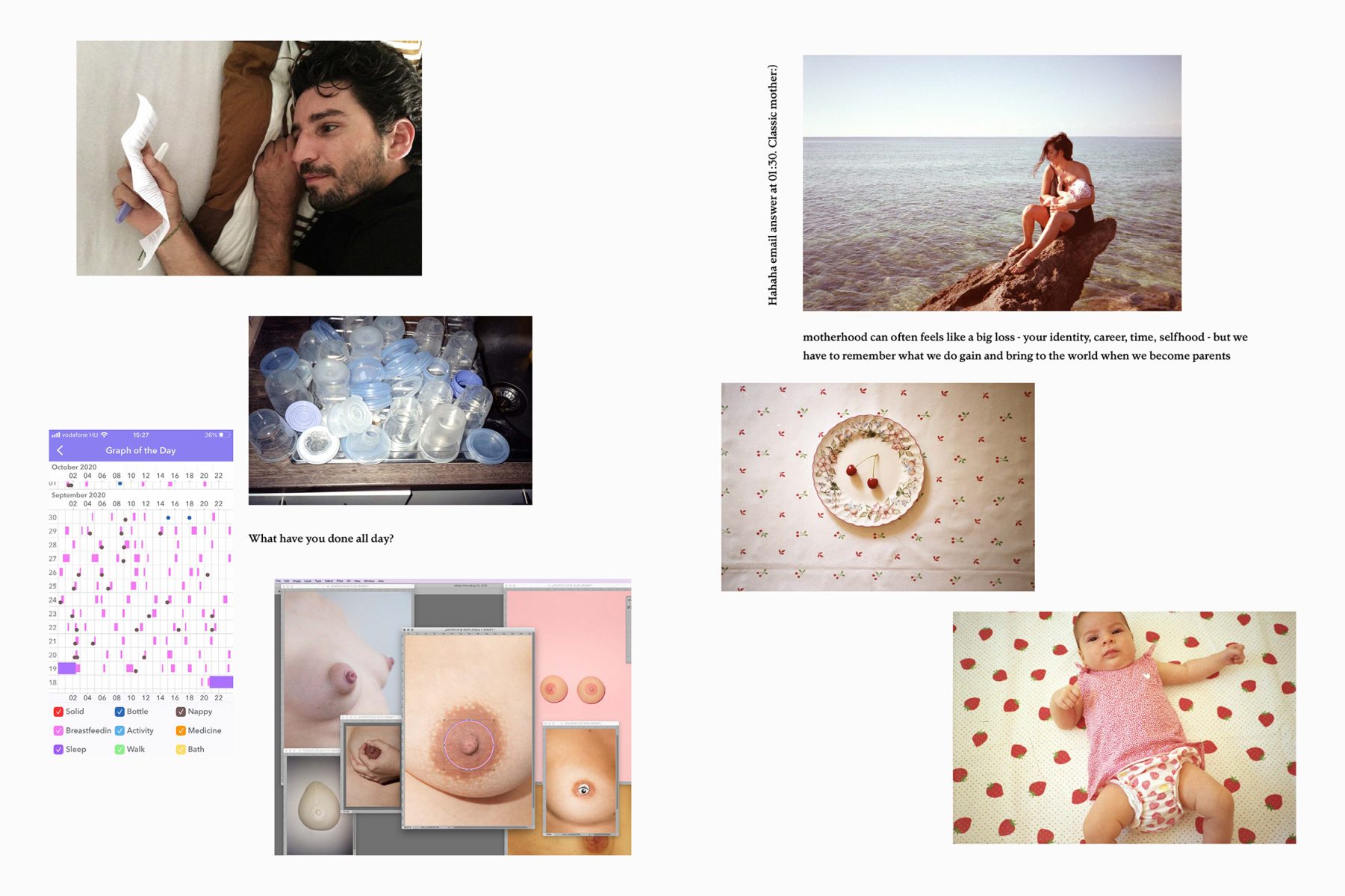

AGV: Yes, I did feel exposed because so much is deeply personal. That’s why we included a six-page diary section—on different paper with smaller photos at the back—because those images felt like a diary. But I didn’t want it to be just my diary. If you flip through the book, you can’t tell whose story it is. It’s a universal tale of motherhood and parenthood, also with images of my husband and other men.

It wasn’t just about my kids, my body, or my experiences. I never had a C-section, but there’s one in the book. I never had my skin broken, but I included images of broken skin. I wanted different perspectives. Living in Hungary limited ethnic diversity, but I tried to ensure the project wasn’t only about me. Some images show my face—when necessary, others are spontaneous, and a few are staged to intensify emotion.

I’ve always explored personal feelings to answer my questions. In that sense, nothing’s different. What sets this project apart is its raw honesty. It shows body parts, but not always mine, so I don’t feel too exposed.

The same goes for my kids. If one day they ask, “Why my face?”, I’ll say it wasn’t just them—there were other children, too. My eight-year-old sometimes opens the book and says, “I didn’t let you take this picture of me”. I tell her, “That’s not you” and she laughs.

ASX: Larry Sultan, in Pictures from Home, had a list of ideas for photographs he intended to take, such as “Walking the dog at night”. Had you planned your photographs similarly?

AGV: Yes, I had a clear list of things I wanted to capture. It was obvious which images were missing. The book is divided into emotions—expectations, reality, transformation (both soul and body), chaos, and resolution. There’s no chronological order, just themes. I had a list of images—some already taken—and carried a notebook, constantly jotting down ideas.

I often tell this story about realizing the book was finished: when my second child started walking, my husband called out to me at the park, shouting, “Come take a photo! She’s walking!” and I just froze. I told him, “I already have a photo of a walking child”. He looked at me and said, “It’s not about the book; it’s about the moment”. That’s when I realized I had forgotten to capture my own child’s first steps because, in my mind, I had already photographed that moment before.

After the book was published, I felt like there was nothing left to photograph. It wasn’t until my eldest daughter lost her first milk tooth that I thought, “Oh, there are still moments that need to be captured”. Then we got lice—something no one had warned me about! That experience isn’t in the book because it mostly begins with school life. When my child started school, it felt like a new chapter—and now, I have a new list.

ASX: Although the absence of page numbers suggests a lack of narrative—and to some extent, that is true—toward the end, we see the children growing older, and you also begin to include your husband in the photographs. Was there a specific narrative arc you intended to create through the book’s flow?

AGV: We didn’t include page numbers because the book is meant to feel like a big, beautiful mess—just like parenting. I wanted readers to open it anywhere, flip to any page, and still find comfort. I also wanted it to feel dense, with juxtaposed images, because these moments—like memories—are fleeting.

Looking back, many images feel different. My kids have grown, and we forget moments quickly. If you don’t document them immediately, they vanish. Now, they seem huge, but an hour later, they’re gone. That’s why I wanted to capture every second.

The arc of the book follows emotions—from expectations, through chaos, to resolution. Parenting feels isolating at first, especially postpartum. But as kids grow, we engage with communities and realize that part of the journey is becoming a parent—a difficult shift. The other part is the unavoidable chaos of raising kids and adapting to it. It’s also about transforming your home to hold space for a family.

That’s why the second part of the book blends chaos and resolution. For me, one image that truly represents making peace with this change is the little stones arranged like a rainbow. It symbolizes finding order within chaos—when you start seeing things with more humor and self-forgiveness.

Some images near the end could just as easily be among the first taken, while some at the beginning were taken toward the end of the six years. There is no set chronological order—just flashbacks moving back and forth.

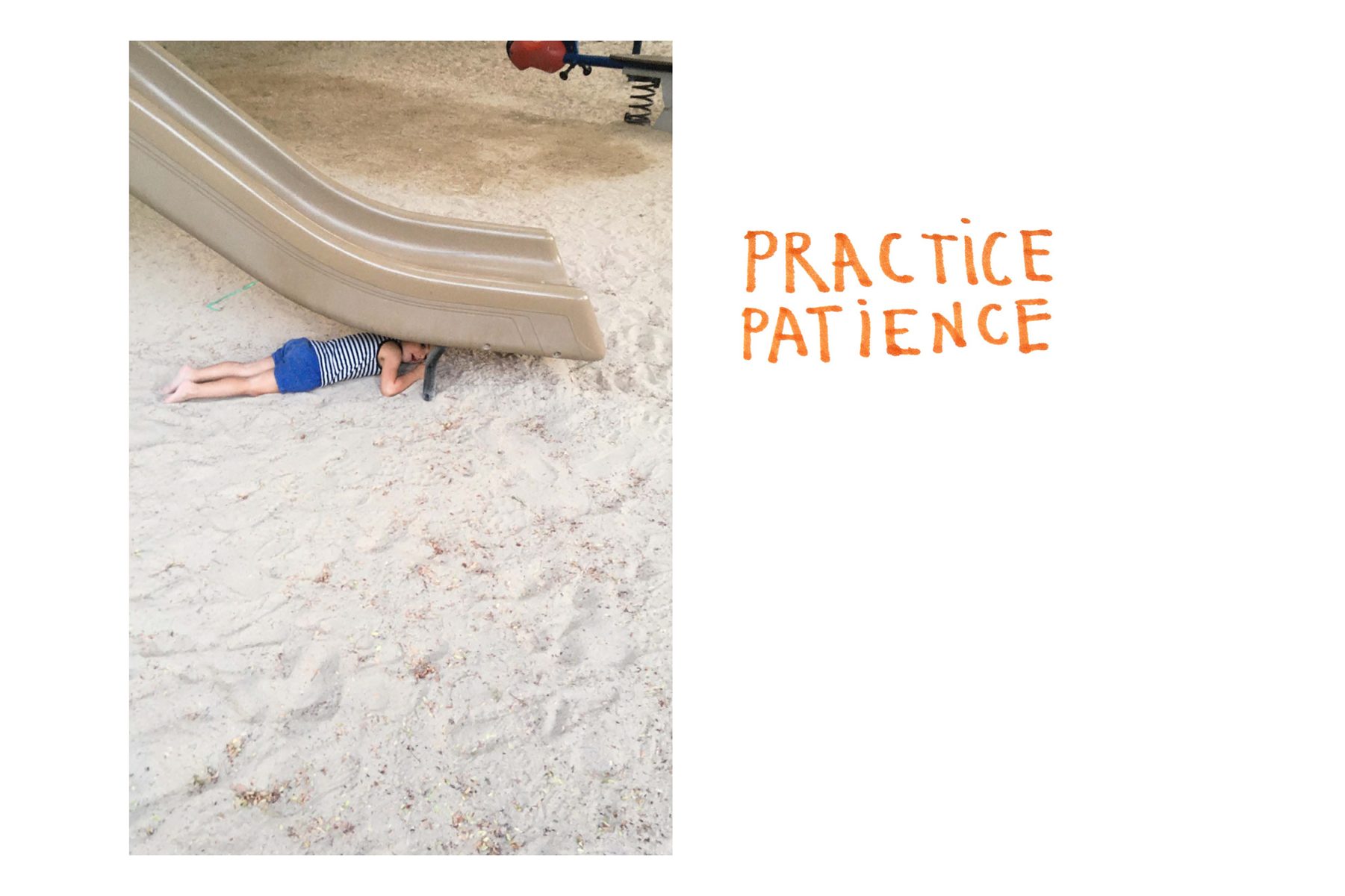

ASX: In one of your handwritten notes with children’s markers, you write that you were trying to “practice patience”. Didn’t the very process of photographing these everyday moments contribute to that?

AGV: I never thought of taking photos as practicing patience, but maybe it was. Patience is critical for an artist—not just in creating but in waiting for feedback, for others to understand what you made. It’s the same with children—so much waiting—for a tantrum to pass, for the night to end. For me, patience is one of the hardest virtues, still out of reach.

In a way, patience is part of creating a book, but maybe not, because I was eager to create. Even when taking photos, I was often impatient. If my kids refused to participate— eventually, they didn’t want to be my models—I sometimes secretly bribed them with chocolate so my husband wouldn’t see.

There was also something funny about it. When they did something naughty—like painting on the wall or throwing shit on the floor—they knew I’d want to photograph it. Instead of being told off, they’d smile, run to me, and say, “There’s something you might want to see”. In a way, it was also learning patience—because some of these moments turned into art. So, they didn’t get in trouble or scolded.

ASX: At this point, I would like to share some photos that caught my attention for different reasons. The one with your child hugging the cereal box after spilling it all over the floor—I could easily imagine this photo printed as a poster at a bus stop or featured on Nesquik’s social media pages. I also find the one where you are lying on the white sheets with your child, particularly striking. The diaper with the glitter. The two children climbing a set of stairs, seemingly heading toward nowhere. The photo that moves me the most is the one with the elderly hands and the child’s back—it feels like a powerful representation of the circle of life. Are there any specific photos that stand out to you?

AGV: I love all these photos, and many mean so much to me. But it’s fascinating how different images resonate with people at different stages of life. Friends who were familiar with the project often return years later, connecting with different images. The book continues to evolve over time.

From the ones you mentioned, the Nesquik photo—I thought about sending it to them, too. It’s one of those moments when my daughter did something, froze, and said, “Photo?”. She knew she might get scolded but also recognized its potential. We arranged it slightly into a circle and it still brings back beautiful memories.

The kids climbing the stairs—I love it because, as you said, they seem to be going nowhere. But learning to climb stairs is a crucial childhood stage. It’s also scary because you have to let go and allow them to get hurt. That’s one of motherhood’s hardest parts—not just protecting them but teaching them how to handle pain and face challenges.

The elderly hand photo is important because it’s not my grandmother’s. A family friend’s hands reminded me of my grandmother’s, so I asked her to hold my daughter. I wanted that contrast between old and new skin.

The raspberry image is also significant. I wanted to include images that aren’t just moments but eternal stories of parenting and childhood. It’s about childhood memories, the things we lived but never thanked our parents for, that we often take for granted. For many, the images reveal what their parents did—or didn’t. That is a quiet revelation.

ASX: There are moments when it seems difficult to imagine that you picked up the camera. In one photo, the baby is sobbing uncontrollably, while in another, its diaper is soiled. Although I am not a mother, I imagine my instinctive reaction in the first case would be to comfort the baby and help it stop crying, and in the second, to clean it up. What were some of the challenges you faced during the creation of this project?

AGV: If you see a sobbing baby, you’ll comfort them—but some tantrums last for hours, and there’s no way to soothe them. They must learn to self-soothe. One of the hardest parts—and part of practicing patience—was realizing that what worked for us was simply being present.

So, no, I don’t think I’ve ruined my children’s lives by photographing them in moments of struggle. The same goes for the diaper moment—it’s so typical, so classic.

For me, these moments reassure parents—they are not alone, it happens to everyone, and there is no single right way to handle them. I believe that showing these moments can be comforting.

ASX: I read on your website about the project: “This work in progress will always be a work in progress…” and indeed, I feel the same way—as you grow, as your children grow. I was wondering what the next chapter would be—if there is one. Then I saw the project you’re working on with your now eight-year-old daughter, If You Knew It, Why Didn’t You Do Something About It? and I get the sense that this question weighs on you: What kind of world are we bringing our children into? Once again, you’re working on something beyond the personal—the climate crisis, political events, and a flow of troubling news. In the end, you ask yourself, “How much do we share with our children about the world’s harsh realities?”. Perhaps you’ve found the right way—you create art together. Does that bring you any sense of relief?

AGV: Thank you for putting it so beautifully into words. This goes beyond the personal—it’s universal. Everyone around me struggles with the same challenge: raising children amid a climate crisis and an uncertain future. Working with my daughter helped because we found a language—a way to ease the pain by expressing things even we, as adults, don’t fully understand. Children don’t grasp concepts like the end of the world—and honestly, neither do we. We’re bombarded with warnings that the end is near. But what does “soon” mean? What does “end” mean? Time is relative for kids. The other day, I told my five-year-old, “Five years ago—that’s nothing, that’s yesterday.” She looked at me and said, “That’s not yesterday. That’s my whole life.” And she was right.

Working together heals. Humour is essential—irony, sarcasm, and self-reflection. Creating together lets ideas flow naturally—far more effective than simply explaining things. As parents, we think we have answers, but confronting our fears reveals how little we know. What perspective can we pass on if we don’t have answers? What makes this project meaningful is that it allows me to say to my children, “I don’t know”.

It started with a single question from my six-year-old: “Are we going to have to run from fires?”. At first, I dismissed it— “Go to sleep, it’s bedtime”. But then I turned back, realizing that’s not a question you leave a child alone with before they fall asleep. I instinctively reassured her— “No, we’ll be fine”. But she wasn’t asking about herself. It was about the world, her future. At that moment, I had to be honest. I told her I didn’t know. And then I realized—she’s only six. She doesn’t even understand what those things truly mean. That’s how this project began—by listening, talking, and asking questions.

ASX: In my opinion, beyond the themes you explore—womanhood, motherhood, parenting in general, gender, and the representation of women in the arts—this work is also an ode to the simplicity of everyday moments, an ode to life itself. Was that your intention?

AGV: I really like your questions. I love everyday things, and I think we don’t give enough attention to the magic of the mundane.

As I said before, every minute passes so quickly, especially with small kids. If you don’t write things down or take photos, they just disappear—you won’t remember them. That was something I wanted from the beginning—I wanted to remember everything.

I still feel that way now because my kids are four and eight. I worry this phase will be over soon. I guess it’s also hormonal—something about the way a woman’s body works. When you know it’s your last child, suddenly every second feels precious—you want to experience it fully. I think if we all lived this way, we’d be happier. Too often, we’re not fully present—it just passes by without being truly appreciated.

ASX: Ultimately, is your project Sorry I Gave Birth I Disappeared But Now I’m Back a love letter or a survival guide?

AGV: Yes, it’s a survival guide, but it’s also like a comic book—one where you can laugh, and often, no explanation is needed. You can simply remember and think, “Oh, that happened to me too”. Or you can give it to someone for comfort, to say:

“See? This is all going to happen to you soon. Enjoy it. Enjoy every second because it will disappear in an instant”.

And when you feel like you’ve disappeared, you’ll realize you’ve been nurturing a human being—and it all happened in just a split second.