Photography has always had a complicated relationship with memory. It promises to hold on to moments, but it also shows how unreliable memory really is. This tension runs through two recent photobooks by one of the most interesting Japanese photographers working today. Family of Lies (Three Books, 2024) and Tebajima (Kawazu Kikaku, 2024), by Hajime Kimura, are different but connected explorations of how photography can express what remains when certainty falls apart, whether in family relationships or in communities that are disappearing.

Family of Lies is both a photobook and a memoir. The photographer himself describes it as an attempt to explain “why I had an intense obsession with ‘the concept of family’ as a community” (all quotations are from an e-mail interview I did with Hajime Kimura). Instead of telling a straight story, the book looks back at Kimura’s earlier projects — In Search of Lost Memories, Path in Between, and Snowflakes Dog Man — and places them in the wider frame of his own personal history. The starting point of the work comes from a break in Kimura’s relationship with memory. After losing both parents — his mother when he was sixteen and his father at twenty-nine — he was left with the unsettling feeling that his memories of family had become “uncertain”.

This uncertainty is both emotional and about time. When Kimura looked at his family albums after his father’s death, he realised he no longer knew when many of the photos had been taken. This confusion between past, present, and future became the basis of the book. Most of the images come from family albums or places tied to family history, but they are deliberately transformed to reflect his current state of mind. Using techniques such as solarization, he inverts and abstracts the images, “turning them into something entirely different from the actual world”. The process is both destructive and creative, recognising that memory may be less about preservation than about transformation.

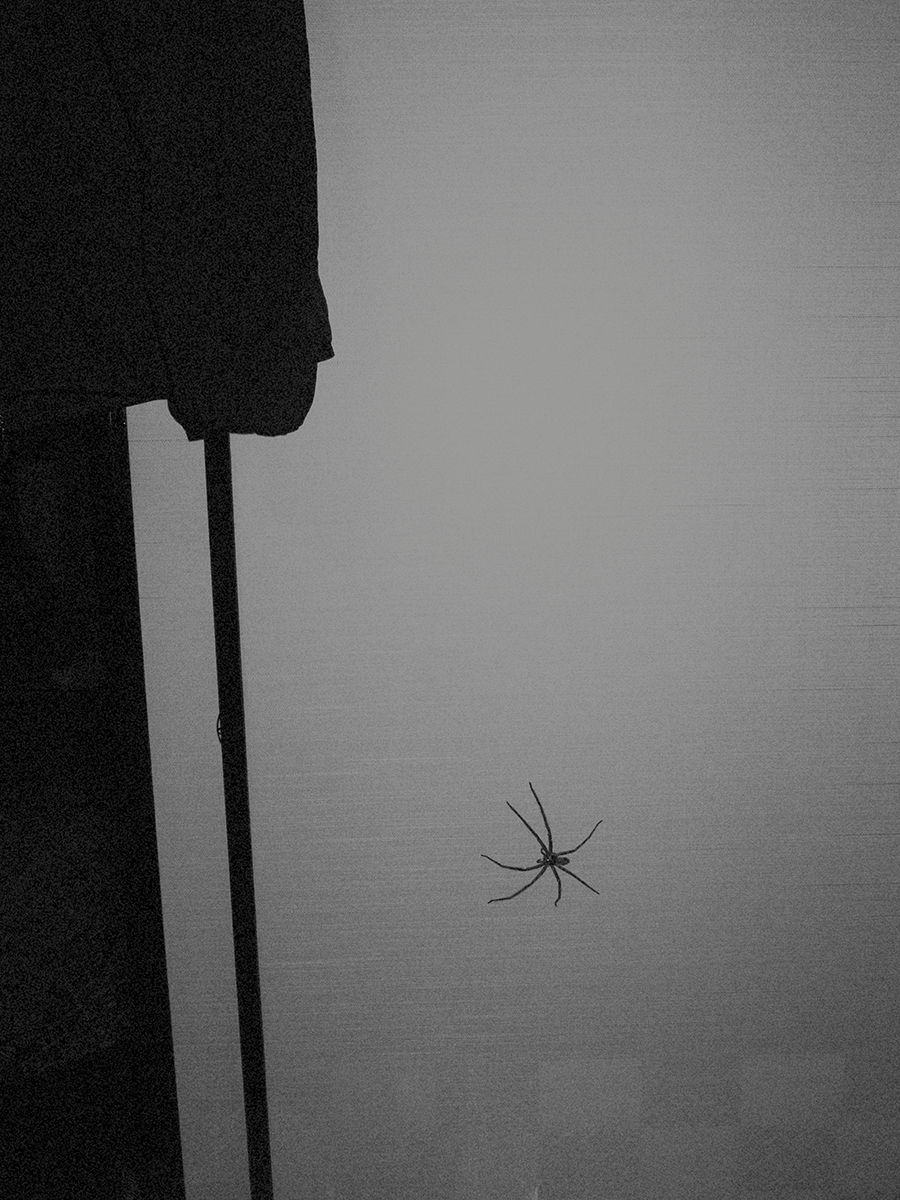

The result is a work that belongs to photography’s lyrical tradition — where the aim is emotional impact rather than factual record. The deliberate blurring, the out-of-focus effects created by covering enlarger lenses with stockings, and the mix of analog and digital processes all build what could be called an anti-archive. While traditional family photography tries to anchor memory in clear evidence, Family of Lies embraces the power of uncertainty

Kimura’s non-mimetic approach places the book in a line of photography that blurs the boundary between documentation and evocation. But his method feels very personal, with technical processes treated almost like emotional gestures. His use of solarization is a good example: the chemical inversion of light and dark makes familiar images look strange and unrecognisable, echoing the way his family memories have been reshaped by loss. What once felt clear now feels foreign — or perhaps it was foreign all along.

Tebajima takes this exploration further, but on the scale of collective memory and the fading of communities. Commissioned by a Tokyo company, the project documents Tebajima, a small island in Shikoku — the smallest of Japan’s four main islands — home to fewer than fifty people and listed as a community at risk of vanishing due to Japan’s shrinking population. Kimura didn’t approach this as standard documentary work, but instead as a chance to explore how demographic decline affects memory itself. The project clearly has an anthropological angle, but without pretending to be scientific.

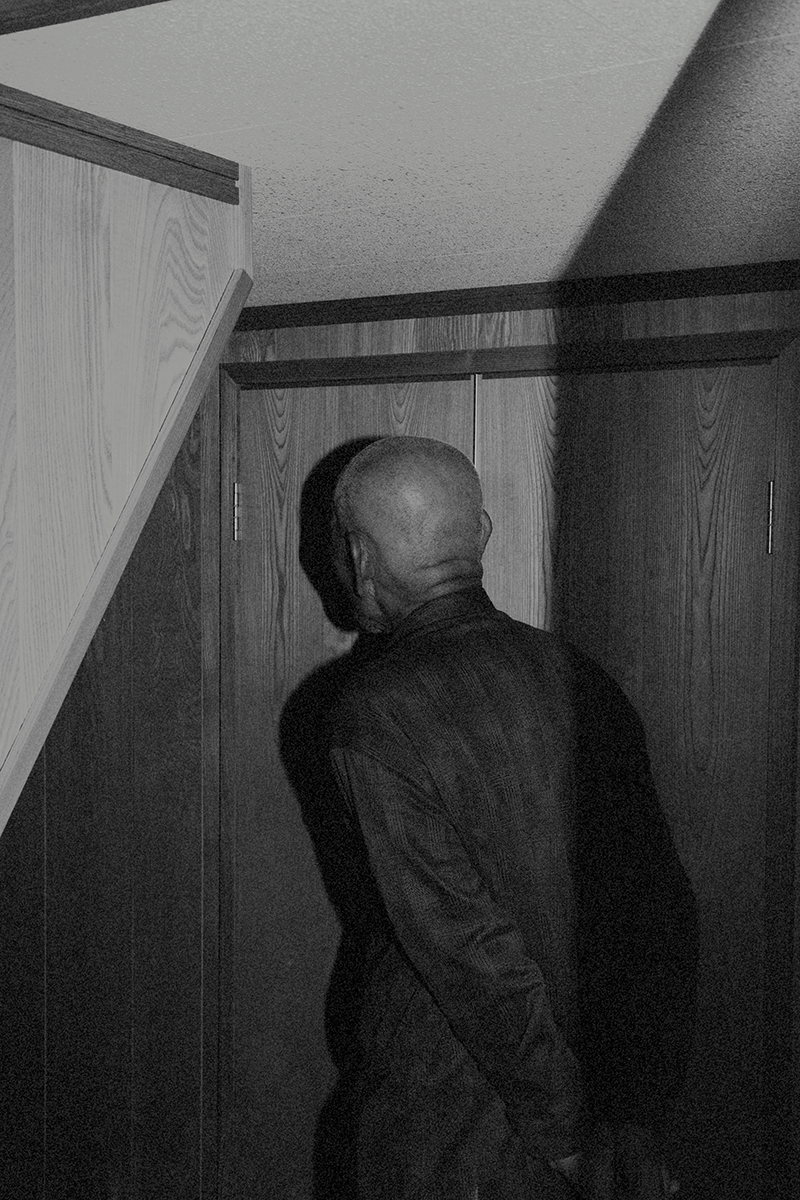

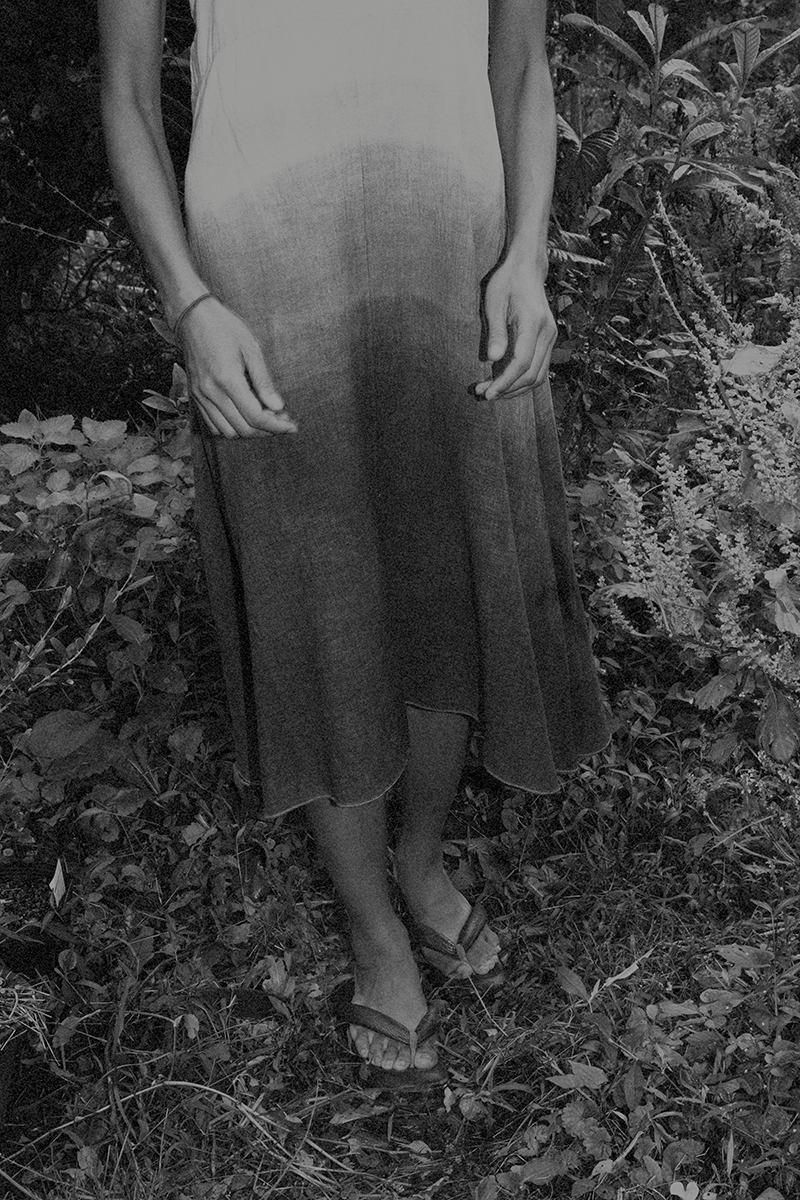

At first, it was meant to be a fifty-day residency during which Kimura would interview and photograph all the island’s inhabitants. But when many women refused to be photographed, the project changed direction. Kimura didn’t see these refusals as failures, but understood them as a material token of absence, a visual sign of those who cannot be seen, much less recognized. This shift made him connect what was happening on Tebajima to something he had already witnessed during his previous eight-year documentation of a mountain village: the gradual disappearance of people from shrinking communities. From this angle, Tebajima’s decline is not unique, but part of a broader condition shared by many small villages across Japan.

This move from the specific to the universal shows a refined way of thinking about ethnographic work — how it can move beyond its immediate subject to touch on wider social issues. The choice to obscure faces also comes from this. Instead of a straightforward portrait series, the project turns into a meditation on anonymity and representation. The islanders become archetypal figures, their personal identities absorbed into a bigger story about demographic change and cultural loss.

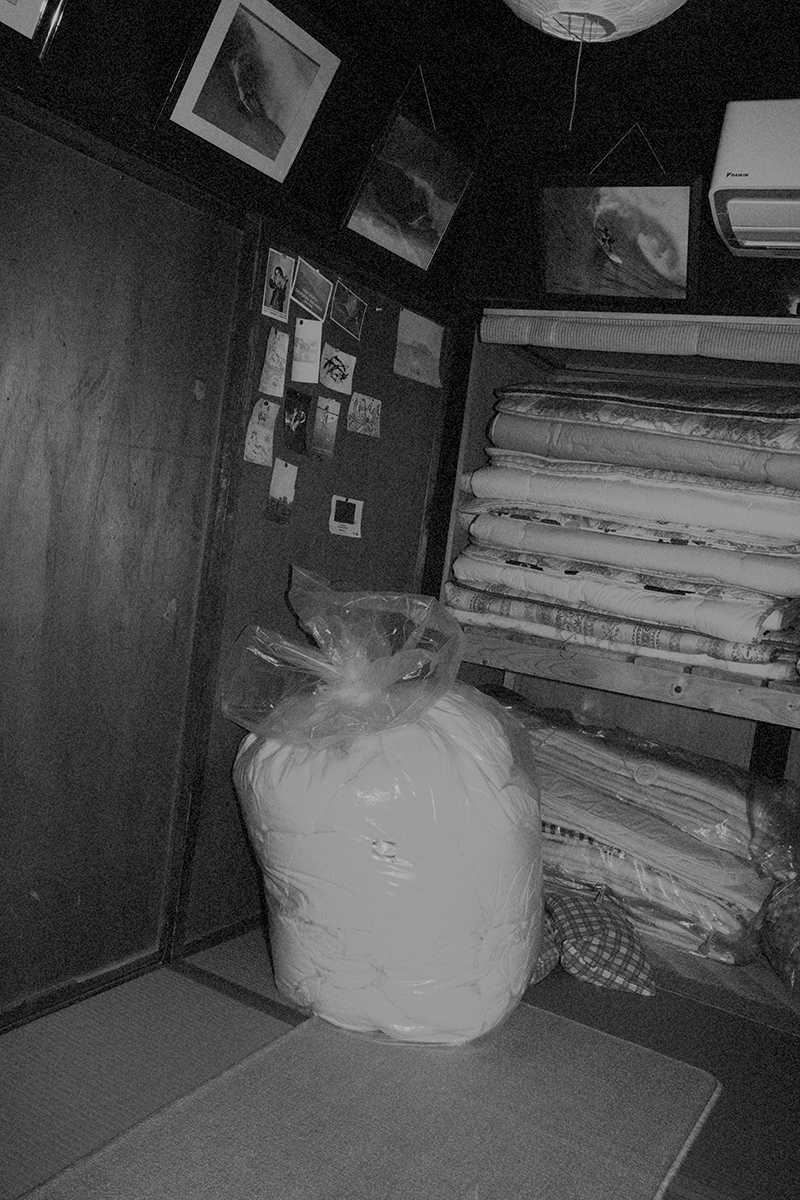

The anthropological dimension also comes out in Kimura’s attention to material culture. He photographs the fronts of buildings “taken in a neat architectural style”, structures that keep construction methods dating back to the Edo period and are found nowhere else. Their slow abandonment and decay capture the community’s fragile condition in time. In one section of the book, across two consecutive spreads, Kimura arranges strips of photographs of the island’s buildings. The sequence recalls Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip and Takashi Homma’s The Ginza Street, where cities are reduced to rhythmic inventories of architecture. But in Kimura’s hands, the gesture takes on a different meaning. By cataloguing Tebajima’s modest houses and shops, he creates not just an index of place but an archive of a disappearance. The repetition of façades acts as a stand-in for the people missing from the frame, highlighting the tension between presence and absence that runs through the project.

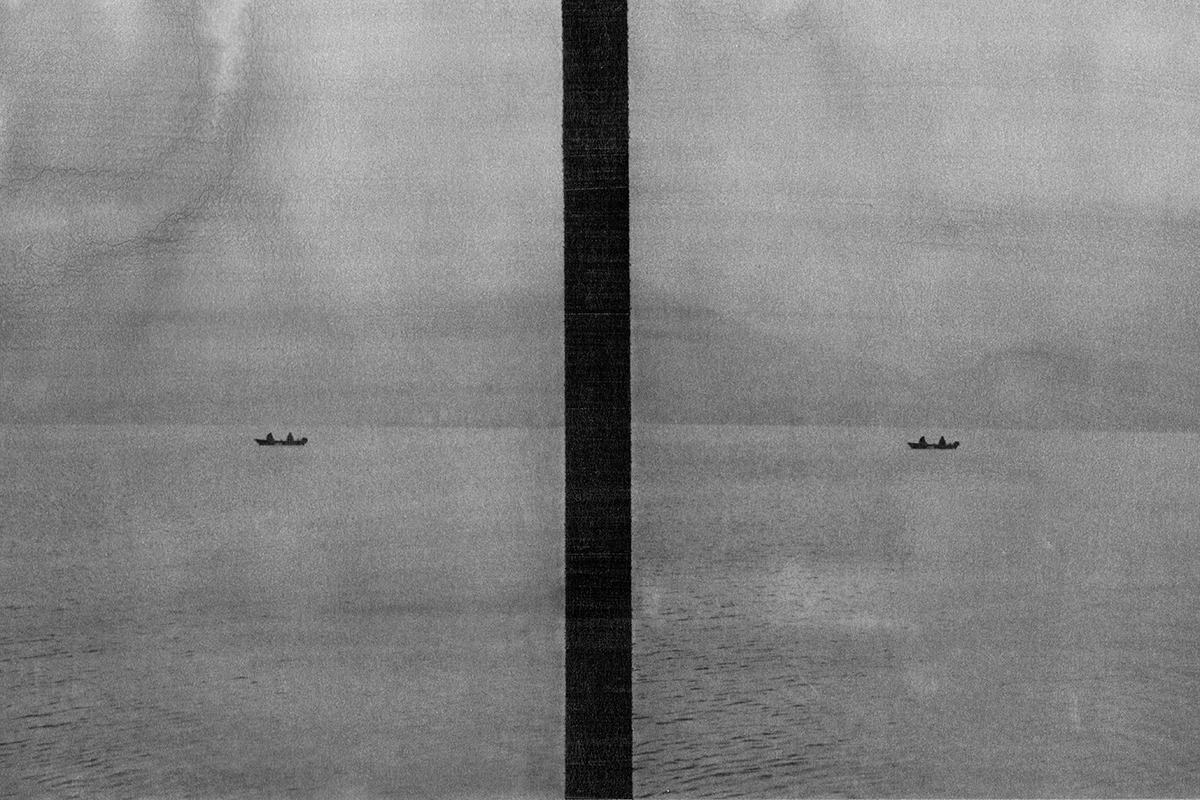

Unlike Family of Lies, Tebajima is not only Kimura’s book. Part of its strength comes from its collaborative structure. He worked with editor Tadashi Shinohara and designer Sho Momma, who contributed to both the layout and the conceptual design of the book. The choice to print in silver ink on black backgrounds came out of this collaboration, producing what Kimura describes as “a silver print glowing dimly against a black background”. The effect recalls both the fishing boats working at night and the fading quality of memory itself.

The collaboration also shaped the text. The book includes interviews with islanders about their daily lives and memories. The designer chose to let the text just barely readable, as a visual metaphor for the erosion of memory. The text is both content and form: its look on the page mirrors the themes of loss and dissolution. The result is truly polyphonic — images, design, and islanders’ voices all exist in dialogue, with no single element dominating. The book suggests another way to think of photobooks: not as the vision of a single author, but as collective works that give space to multiple voices.

The material decisions also carry meaning. Choosing silver instead of white ink shows a careful awareness of how physical qualities can express concepts. As Kimura notes, “white would make the image too clear. Silver has weaker contrast, and depending on the angle, it reflects light to create a distinct look”. Again, in line with his wider work, the shifting surface of silver becomes a metaphor for the instability of memory, where an image changes with perspective and context.

Taken together, Family of Lies and Tebajima approach memory from two temporal directions. In Family of Lies, memory is reworked in the present, as Kimura reframes his family history through old materials. In Tebajima, memory looks toward the future, recording a community and its traces at the very moment they risk disappearing. One project turns memory into a way of negotiating personal history; the other creates an archive for histories yet to be remembered.

Together, they show how photography can engage memory not just as a record of what has been, but as a way of imagining what might remain. Rather than claiming authority as documentary truth, both books acknowledge their subjectivity while asserting their value as interpretation and exploration. They suggest that photography’s power may lie less in preserving memory faithfully than in giving shape to its contradictions, uncertainties, and transformations.

Hajime Kimura

“Family of Lies” and “Tebajima”

Three Books & Kawazu Kikaku

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ José Bértolo. Images @ Hajime Kimura.)