The work of late American photographer Francesca Woodman, produced from the mid- to late-1970s, displays a unique artistic displacement and transformation of ‘feminine’ identity.

By Georgie Boucher, January 1, 2007

In 2003 I was lucky enough to attend an exhibition of Francesca Woodman’s photography from the late 1970s. I believe it was an occurrence of serendipity that I came to enter Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket Gallery and subsequently came to write about Woodman for my thesis. I ran into an old dear friend from Melbourne at the Edinburgh Spiegeltent one night and she described an exhibition so evocatively that I knew instantly it must have been Woodman’s. She told me where the gallery was and I went the next day, where the experience of viewing Woodman’s beautiful, agonised images would stay with me till now. This paper attests that Woodman uses her own body as subject/object to create a sense of fleeting (or serendipitous) femininity that passes between the polarities of presence/absence, woman/ environment, pain/hope and human/corpse, forming a feminist identity that is strategically ‘in-between’ and transient.

The work of late American photographer Francesca Woodman, produced from the mid- to late-1970s, displays a unique artistic displacement and transformation of ‘feminine’ identity. The artist’s exploration of the female body, subjectivity and representation significantly prefigured later feminist art themes and processes, such as those addressed by American women photographers during the 1980s, including Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman. (1) Woodman began producing photographs at the age of thirteen, and worked solidly until her suicide in 1981. Born in Colorado, she studied at the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, and the body of her work was produced in response to school assignments. From her time spent in Rome on scholarship and in New York after completing her degree, she produced an oeuvre that is often described as brief yet powerfully accomplished. (2) Woodman photographically blurred and mutated her body via a deft mastering of prolonged single exposures. In these images, her body traverses dilapidated interiors, is sometimes lodged behind disintegrating scraps of wallpaper, and often appears to move across space despite the static nature of the form, her edges foggy and shifting.

A common motif to Woodman’s imagery is that of her own, or her models’, naked or partially-clothed body refigured as ghost-like or angelic and captured in moments of disappearance, displacement or transformation (Angel Series, 1977-78; House Series, 1976). This investigation is interested in the ghost as a departed spirit who returns to earth as an apparition from ‘beyond the grave’ or from a place somehow beyond existence, possessing the ability to linger in-between the realms of life and death. Despite the ghost’s seeming elusiveness from representation, those of ancient folklore, as well as more recent literary and filmic representations, have been depicted as disturbing, fleeting images of blurred white light and transparent, floating human forms. (3) By extension, the angel also provides a figure of ‘otherworldly’ significance. The angel has frequently been depicted as a guardian or messenger that is non-human yet whose biblical and artistic representations conjure images of winged, ethereal female bodies that may fly beyond mortal existence. (4) Rather than bearing spiritual or biblical connotations, Woodman appropriates the transgressive nature of the ghost and angel that can move across boundaries.

Woodman’s compositions of blurry, obscured figures, floating, crumpled fabric, sheets and paper, and surreal, bizarre objects within the decaying walls of dilapidated houses appear like dreams or hauntings.

Woodman’s suicide at the age of twenty-two encourages the assumption that the young artist was consumed with a struggle to escape from life, as well as a fascination with mythologies of ‘the afterlife’. However, Chris Townsend suggests that reading Woodman’s work for images of death is a romanticising practice and instead believes that her work demonstrates a more complex sense of indeterminacy. (5) Departing specifically from Townsend’s focus on the sense of indeterminacy in her photography, this paper asserts that Woodman’s photography bespeaks more than merely the tragedy of her suicide. This paper will investigate the figure of the ghost or angel as a critically in-between identity in Woodman’s art that defies oppositional categories such as life/death, girl/ghost, presence/absence, woman/environment and subject/object. These new readings of Woodman’s images will explore why it is the in-between nature of the transitional ghost or angel figure that enables a new sense of feminist agency to be deciphered in her work.

RESISTANT ACTS OF VANISHING

Woodman’s compositions of blurry, obscured figures, floating, crumpled fabric, sheets and paper, and surreal, bizarre objects within the decaying walls of dilapidated houses appear like dreams or hauntings. Herve Chandes believes Woodman captures a ‘ghostly and evanescent presence of her own body in movement’, (6) indicating the way in which it is not merely the eerie content of her photographs but also the aesthetic of movement that enables their hallucinatory style. The Angel Series, planned and begun in Providence, Rhode Island, and completed in Italy after Woodman’s graduation in 1978, demonstrates her penchant for capturing moments of disappearance and transparency. These include images of flight, where Woodman jumps into the air as the shutter releases so that the final image is of her as a floating blurred apparition, long blonde hair billowing and white skirt ruff led with air, her black stockinged feet disconnected from the floor (Untitled, Angel Series, 1977). The series also includes the artistic indication of the trace: ghostly markers that suggest a presence has come and gone and perhaps still lingers. One such photograph depicts Woodman’s figure vanishing beneath a blurred white bed sheet within a grove of olive trees, with only her white skirt, ankles and shoes remaining visible (Untitled, Angel Series, 1977).

Static images of fluid flight, trace and vanishing capture a sense of movement, where blurred bodies appear to continue moving as we view them. Peggy Phelan identifies that this series was influenced by the physical suspension of statues of angels in Italian cathedrals, which appear poised between heaven and earth. (7) Woodman constantly suggests that she has the power to enter other worlds, indicated by the traces of exits and entrances from the spaces she inhabits. She appears to melt into walls and floors like a ghost and morph into shapes that defy the fixed physicality of her body. Helaine Posner elaborates:

In her series of ethereal Angels (1977-78) she hovers in a realm

between matter and spirit … the artist seems impossibly light and

disembodied, like an angel about to disengage from the world. (8)

In this sense, Woodman’s photography of angel and ghost women creates critically in-between identities that seek escape and disengagement from the female form. The ‘she’ in Woodman’s photographs is no longer human female but a disembodiment of imagination and desire. Recently, performance theorist Katherine Mezur formulated a notion of the ‘phantom woman’ as a figure of feminist resistance. Mezur referred to the ghost-like female performers in the Japanese performance troupe Dumb Type, observing that the ‘phantom woman’ is characterised by dance-like movements of ‘transparency, translucency, and degrees of erasure’. (9) These acts are also particular to Woodman’s photography. Mezur believes such disappearing acts are resistant acts of vanishing, because the flesh of the phantom women is ‘untouchable’ (10) by external forces of dominance. Mezur conceptualises that the resistant phantom woman in the performances of Dumb Type critiques restrictive Japanese social roles of femininity, opening them up to metaphorical acts of transformation. This analysis is informed by Mezur’s notion of ‘phantom woman’ as strategic feminist identity by suggesting that the subversive figure may also be recognised in Woodman’s photography, despite the strongly different context of femininities. Mezur’s conclusion that the figure of the phantom woman leaves a sense of vagueness and unease about her identity (11) may be applied to analysis of Woodman’s ghosts and angels which dislocate easy, fixed constructions of girl, female and femininity.

Woodman achieves agency through movement, hesitation, uncertainty and displacement within an art form that has traditionally functioned as a discursive device which solidifies identity through technical fixity; this in itself is remarkable.

In two photographs entitled ‘On being an angel’ (Providence, Rhode Island, Spring 1977), (12) Woodman composes the shot so that her head and upper torso appear to occupy an impossible position within the bottom of the frame in the first image, and at the top in the second image. She has thrown her head back so that her bottom half cannot be seen, and her head, neck, shoulders and breasts appear detached from her body, floating and glowing. This nude is positioned so as to baffle rather than please the eye, displaying Woodman’s ability to distort the viewer’s expectation. The ephemeral atmosphere of her images and the repeated motif of the ghost or angel capture the fragility of femininity, but also create a mutable and moving feminine body. Woodman enables a metaphorical freeing of her identity from a static, visible female body available for objectification and consumption by photographing herself as ghost and angel. In this sense, Woodman’s ghosts and angels open out photographic representation through a ghostly ambiguity and obscurity. Woodman achieves agency through movement, hesitation, uncertainty and displacement within an art form that has traditionally functioned as a discursive device which solidifies identity through technical fixity; this in itself is remarkable.

Marilyn Ivy’s theorisation of the metaphorical figure of the ghost suggests that it:

constitutes a discursive world which haunts this world with its

exemption from meaning. What the figure … of the ghost spectrally

embodies … is the recalcitrance of representation itself, the

impossibility of stabilising meaning. (13)

The way ghosts fracture the representative binaries of presence and absence, life and death reveals their liminal non-existence in-between recognised states of being. The meaninglessness of this unknown (moving) position allows it to resist the oppressive authority of representation. This analysis believes Woodman’s ghost-like angels are recalcitrant from the patriarchal representation of femininity that equates true femaleness with an objectified feminine body. Her ghosts destabilise the meaning of femininity by enacting a simultaneously traumatic and utopian exit from lived female bodily experience to somewhere else altogether. Woodman created such illusions with the use of light index, shutter speed, time elapses and chemical shifts, where she herself seems to become a photographic effect. David Levi-Strauss comments that the way in which Woodman places her body between transparency and ref lection indicates an attempt to go ‘through the looking-glass … into a world before the fall into representation’. (14) The ghostly movement of Woodman’s photography enables this flight from representation.

When Woodman appears pinned and hung to a crumbling wall by her hair, when her hand searches through a hole in the concrete wall, when her arms take on the bark-like texture of the trees around her, when she slides across the wallpaper, hangs from a door jamb or holds a mirror to cover her face and reflect the opposite wall, she traverses the passage between body and not-body, body as external construction and body as self-creation. The following analysis will discuss two specific strategies of the ‘in-between’ enabled by Woodman’s creation of a femininity becoming ghost or angel: the disintegration between femininity and environment, and between Surrealist representation of femininity and her own sense of self-determination.

BETWEEN FEMININITY AND ENVIRONMENT

Woodman claimed that she was interested in ‘the relationships that people have with space’ (15) and created ghost and angel female bodies that move between the oppositions of inside/outside, self/ surroundings. Sollers observes in Woodman’s work that: ‘When one doesn’t really exist, except in the impossibility of being an angel … one has a tendency to float, to levitate, for space and weight obey new laws.’ (16) The ghost-like identities of Woodman’s photographs appear like apparitions due to their unique relationship to the rooms and spaces they inhabit, defying gravity and the possibilities of human movement. The literal blurring in Woodman’s shots between the fixed subject and the space it moves through creates images of liminal and unstable figures and places. This instability works to ‘simultaneously create and explode the fragile membrane that protects one’s identity from being absorbed by its surroundings’. (17) Just as ghosts mythologically possess the ability to ‘walk through walls’, Woodman’s female ghosts melt into and move through the locations that seemingly enclose them.

The ambiguity of Woodman’s photography means her works both reveal and conceal identity, paradoxically asserting and denying a sense of self.

In the House Series of 1976, Woodman’s blurred figure is seen beneath a window frame in a room of a crumbling house. She appears seated but leaning, with one foot outstretched in a girlish shoe. The outline of her bare leg is unclear, her face and gaze at the camera are barely in focus, and her body is obscured by a large curled piece of wallpaper that she has wrapped across her front. The effect is of a body floating above the bare floorboards. Light falls on her blonde hair, melting the top of her head into the overexposed trees outside the window. Woodman points the camera into the light and dissolves into the bright sunlight above her. As ghost, Woodman is both part of the wall and part of the light, and her body is unfixed from clear definition. Her apparition merges with the debris on the floor, while the exposed layers, cracks and black holes in the plaster indicate a disintegration of the boundary between interior and exterior space. The two large windows opening on to white light and trees hint at ‘other worlds’, and a piece of the wallpaper that adorns Woodman edges over the window frame into the light. In ‘House # 4’, seemingly shot in the same room, Woodman’s figure moves awkwardly across the floor between the fireplace and the wall behind, one leg either side of the pillar supporting the mantelpiece, and her upper body severely blurred in movement, making her appear faceless. Although it is clear that Woodman has constructed this passage between the fixed structures of the room by moving the fireplace frame away from the wall, the strange physicality of her position and the almost fierce, desperate nature of her movement leaves an impact. This time, the print of her thrift-shop dress matches the peeling floral wallpaper beside the window above her, and the ghost-like fleeting nature of her upper form dissolves into the darkness of the fireplace, suggesting the merging of woman and domestic interior.

Solomon-Godeau suggests that images such as these depict the vulnerable female attempting to conceal herself against entrapment. Woodman’s obscuring of her naked figure within the space of home is read as an enactment of ‘entrapment, engulfment, or absorption of the woman in those spaces–both literal and metaphorical–to which she is conventionally relegated.’ (18) From this perspective, the way Woodman inhabits the spaces of home, deliberately disturbing physical and psychological boundaries, is interpreted as an analogy to the house as imprisoning space of woman’s worldly exclusion. (19) Such readings position Woodman as vulnerable to the house, which threatens to engulf ‘her fledgling statements of self’. (20) In this sense, the metamorphosis of the female body into the physical building of the home enacts a patriarchal erasure of feminine identity imprisoned within the discursive spaces of family, domesticity and servility. This investigation takes an alternative stance to Solomon-Godeau on this matter because it believes that such readings succumb to stereotypical connotations of a young woman’s body as endangered and fragile. Further, they fail to identify the exits from and transformations of femininity that empower Woodman’s configurations. Woodman’s images of displaced and incomplete phantom figures appear to this investigation as interrogations of the way we understand bodies and subjectivities, rather than an erasure of the self.

As Woodman sits, naked except for her shoes, a foggy, smudged outline of her figure on the floor at her feet, a yearning is communicated by the seated figure to be free of her female body and inhabit instead the phantom-identity on the floorboards (Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976). (21) In another piece from the Angel Series, only Woodman’s bare legs are seen, her feet apart and on tippy-toe in a room of decaying walls and a dirt floor. Like a mirror image, on the ground at her feet two diagonal channels are carved into the dirt and matched to the size of her legs. In parallel to the previous photograph, this collapsing of Woodman’s body and the physical space that she inhabits defies the fixed boundary of her own feminine form and moves beyond it in lines of displacement that become the floorboards or the earth at her feet. Like the notion of the restless or ‘unquiet dead’ who return to disturb humanity by seeking atonement, vengeance or retribution, (22) Woodman’s ghosts disturb traditional understandings of truth and falsehood, real and unreal. Despite the deep disturbance that is infused into Woodman’s ghostly portraits, they indicate an empowered refusal of ‘real’ definitions of identity, by defying the permanent positions of presence or absence, flesh or environment, body or trace.

The ambiguity of Woodman’s photography means her works both reveal and conceal identity, paradoxically asserting and denying a sense of self. (23) The physical exchanges Woodman undertakes between her body and the built or natural environment that surround it reveal a strategic movement between fixed states of being in order to defy easy categorisation of her identity. These photographs disrupt the availability of the naked feminine body for consumption, and instead attempt escapes from feminine physicality through fluidity and ambiguity.

PROBLEMS OF TRANSITORY IDENTITY

However, when regarding the ambiguity of Woodman’s images, it becomes clear that formulating precise notions of feminist agency is problematic. While the figure of the ghost is understood to be a metaphorical identity that gains empowerment via strategies of disappearance and dislocation, the critique of fluid identity is also a solid argument that must be tackled when proposing that it is a position of transgressive power. Postmodern feminist art theory has dedicated much to post-structuralist understandings of identity as multiple, contingent and discursive, and the compelling manifestation of these understandings in art that interrogates identity. However, a simultaneous feminist concern with a loss of stable identity has launched an important investigation of the concepts of fluidity, deconstruction and relativism as they relate to gendered identity in both theory and art. While the dissolution of boundaries, such as those discussed in relation to Woodman’s form and femininity, may be examined as productive trangressions of locked patriarchal positions, the binaries that govern Western subject formation also allow for corroborated identity within society, and an accepted position from which to speak. Feminist critique of postmodern theory which celebrates fluid subjectivity is encapsulated by Seyla Benhabib’s comment that ‘The postmodernists’ positions thought through to their conclusions may eliminate not only the specificity of feminist theory but place in question the very emancipatory ideals of the women’s movement altogether.’ (24) According to Benhabib, along with the dissolution of the subject, the concepts of intentionality and accountability disappear. Through this lens, arguing that Woodman’s ghost and angel figures constitute effective feminist imaginings of identity may be criticised for ignoring the way her ghostly dispersal of the fixed, identifiable female body/identity reduces the political status, intentionality and accountability of the feminist subject. However, Claire Colebrook talks back to this line of questioning when she asks from the opposite perspective: ‘Can feminism be a subject or identity when these concepts have for so long acted to … subordinate thought?’ (25)

This analysis acknowledges the problematic nature of highlighting the ghost as a figure of political feminist agency, but also proposes that reflecting back on Woodman’s photographs of the 1970s in light of Colebrook’s contemporary question reveals the power of her images in new ways. The ghosts and angels of Woodman’s oeuvre are figures of fluid femininity and, therefore, as Benhabib might suggest, identities of disempowerment and disappearance. However, viewed from Colebrook’s elucidation of the reasons why feminism must defy fixed identity, it suggests the risky yet powerful terrain of a critically in-between subjectivity. Rather than the creation of complete, coherent female subjectivity as a figure of political engagement, Woodman’s ghosts and angels constitute an artistic investigation of feminine identity that predated Colebrook’s concerns but still sought the movement beyond crystallised identity that recent feminism desires. Feminism continues to value the art of women that imagines gender, the body and existence in creative, complex ways which contribute to a politics of feminine experience. While Benhabib’s warnings are applicable to analysis that overestimates the connection between art and political reality, it is evident that Woodman’s photographs imagine femininity in creative ways which remain powerful to an unfinished project of liberating women from the confines of their bodies and their gender.

IN DIALOGUE WITH THE SURREALIST PATRIARCHS

Surrealism has long been regarded a patriarchal and even misogynistic art movement by feminist art critics. These critiques are based on the notion that male Surrealists were inclined to elaborate and celebrate an ‘otherness’, assigned primarily to the feminine. (26) In ‘Ladies shot and painted: Female embodiment in Surrealist art’, Mary Ann Caws identifies the way Surrealist images of feminine bodies eroticised this sense of Otherness through the functions of fetishisation and objectification. (27) Caws refers to the example of Andre Masson’s mannequin sculpture, which he created for the Surrealist exhibition of 1938. Masson modified the found object of the female mannequin by placing a bird cage over her head, masking her mouth and underarms with pansies, and placing a decoration made of peacock feathers over the join of her thighs that appears to represent fallopian tubes. Caws elaborates that such a mute, trapped figure is a Surrealist construction of femininity par excellence, whereby she is contained, fragmented, exoticised and available for visual consumption. Hal Foster writes that the Surrealists were interested in the psychoanalytic notion of primal fantasy and hoped to evoke such childhood fantasies and memories through creating fetishistic scenarios in their art. (28) From this perspective, Masson’s rendering of the mannequin may be read as a deliberate collage of fetishes, such as the pansies or feathers as nonsexual objects imbued with a compulsive sense of eroticism. From a feminist perspective, the Surrealist deferral of the female form on to these objects and others such as hats, gloves, furs, animals and plants is a patriarchal process that works to fragment and dislocate the threat of castration associated with the female in psychoanalysis.

Further, many feminist re-evaluations of Surrealism have focused on the difficult relationship female viewers and artists have had to fetishised Surrealist images, in which their position is necessarily split between the gaze of the viewer that is codified as masculine and identification with the feminised object offered up for consumption. (29) Helen Chadwick’s Mirror Images: Women, Surrealism and Self-Representation suggests the complex relationship female lovers, muses and artists within the movement had to Surrealist constructions of the feminine. Chadwick explains the unique position of female Surrealists and Surrealist-inspired female art to investigate the problematics of female self-representation that are inextricably bound up with woman’s internalisation of these very images of her Otherness: as object of male desire, image and fetish. In this sense, female Surrealist artists were positioned to collude with their own objectification, staging and enacting an inability to differentiate their own subjectivity from the condition of being seen. Woodman’s explorations in photographing herself exhibit this fraught relationship to her own gendered identity, articulating how the body is marked by femininity and aligning her with the women Surrealists who took their own bodies as a starting point to collapse interior and exterior perceptions of the self. (30)

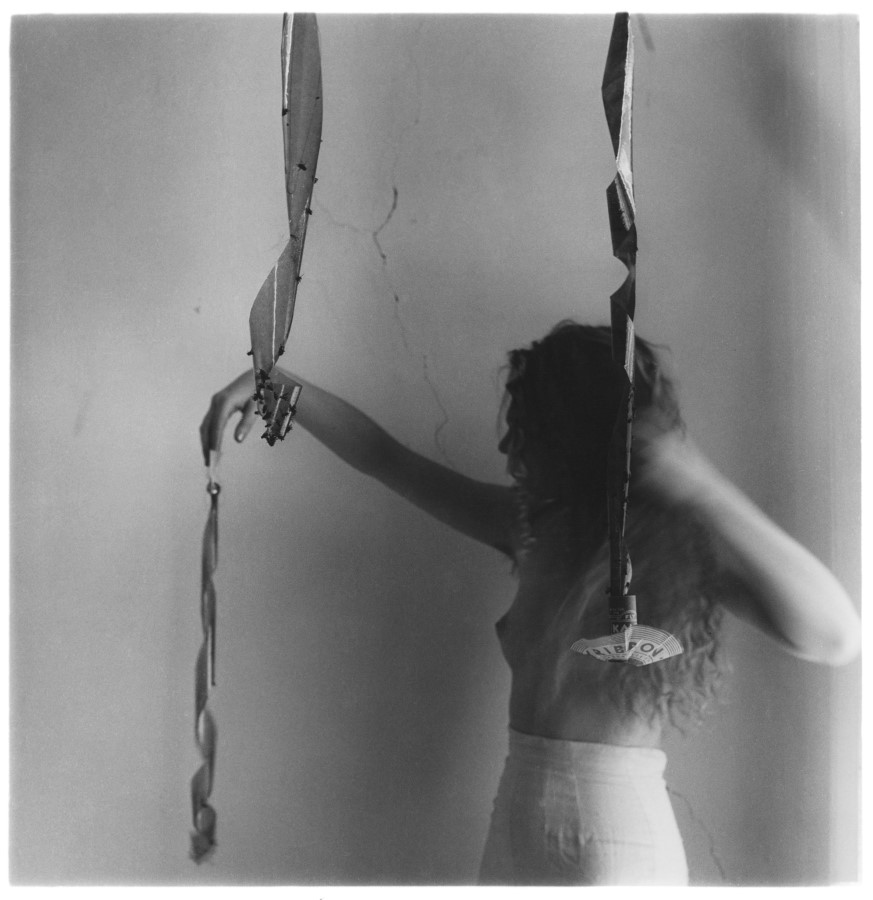

The flesh of her back is revealed and she bends her hand back to hold a large fish bone along her spine. Her other arm is bent in front of her face and she leans into it, shielding her eyes.

Criticism of Woodman engages with the thematic and stylistic connections that are drawn between her work and that of the Surrealists. Woodman appropriated Surrealist tropes, such as plant forms, animals, mirrors and romantic ruins, as well as spatial and temporal distortion in her work. She held a collection of ‘object-talismans’ that echoed the fetishised found objects of artists such as Andre Breton and Man Ray, including gloves, umbrellas, costume jewellery and furs. (31) However, on a more complex level, her photography demonstrates the influence of a challenge to oppositional distinctions between self and other, inside and outside, conscious and unconscious also found within Surrealism. Feminist criticism attempts to interpret whether Woodman’s references to Surrealism are that of inspiration or rather ironic critique. The ghosts and angels of Woodman’s compositions elude an understanding of female being as ‘to be looked at-ness’ through a feminist sense of vanishing and disappearance. Further, Woodman, like the female Surrealist artists before her, enacts the patriarchal Surrealist feminine imaginary, performing acts of self-objectification and implicating herself in the patriarchal projection of woman as other. This strategic implication serves a feminist artistic function by simultaneously revealing the way femininity dictates that a woman must ‘see herself’ to attain self-identification, as well as subverting the fetishised, objectified female form by injecting it with a lived experience of femininity. (32) Woodman altered the Lacanian formulation, ‘You never look at me from where I see you’ (33) when she commented, ‘You cannot see me from where I look at myself.’ (34) This statement hints at the empowerment of a female artist taking up the position of active looker, as well as the difficulty of distinguishing between different ‘looks’ within photography–the gaze of the camera, the artist, the model, the gaze of introspection and the gaze of the viewer.

In an untitled piece shot in New York in 1979, Woodman leans up against a decaying wall with her back to us, dressed in layers of thrift-shop dress material. The flesh of her back is revealed and she bends her hand back to hold a large fish bone along her spine. Her other arm is bent in front of her face and she leans into it, shielding her eyes. The fish bone is shiny and translucent, and the pattern it throws across Woodman’s smooth back forms an ‘L’ shape with the similar diagonal black markings that are exposed on the wall. The placement of the fishbone mimics the fetishism and fragmentation of the female form so often replaced or juxtaposed with bizarre objects in the work of the Surrealists. Yet Woodman’s pose offers a different mood from the typical presentation of female Surrealist object. The aestheticisation of her body through the holding of the bone and the connection to the pattern on the wall is an act of self-adornment or contemplation. The image of her head in the crook of her arm and her back to us disallows the ability of the viewer’s gaze to dominate her. Instead, engaged in a conscious artistic modification of her own body, Woodman seemingly closes her eyes in a reflective mood of introspection, entering the place where she imagines or looks at herself, a place that ‘we cannot see’.

This investigation attests that Woodman’s unique relationship to, and appropriation of, Surrealism furthers the interpretation of her style as strategically ‘in-between’, by understanding the dialogic nature of her work as suggested by Susan Rubin Suleiman. (35) The term ‘dialogue’ refers to discussion, conversation or exchange between people, and thus entails a figuration that is productively in-between and non-hierarchical. This section of analysis extends the critically in-between nature of Woodman’s images by recognising the way her works construct a sense of dialogue between patriarchal constructions of the feminine within the male-dominated Surrealist movement and her own constructions of self-determined femininity. The conversation between these inherited Surrealist fetishisations of femininity and Woodman’s own refigurations of such icons that one hears when viewing such images, discuss issues of ownership, agency, sexual empowerment, self-objectification and appropriation. These ideas, which are implied by a sense of visual exchange between Surrealism and Woodman, are dialogic rather than didactic, as they offer no clear conclusions or opinions. Suleiman suggests:

Dialogism … is … staged by the critic who juxtaposes works and

makes them speak to each other … To perform such staging, the

contemporary feminist critic must herself participate in a ‘double

allegiance’ … In this case, the only ‘good’ critical position is

one that shuttles between positions. No stasis. (36)

Instead, like the exploratory nature of art, the dialogic ideas in Woodman’s work that are of great importance to feminist art analysis are engaged with in a manner that asks questions, deconstructs, and imagines possibilities for traditional constructions of femininity as well as their reconstruction for agency and empowerment. Suleiman formulates that the way Woodman composes images of her own body that parallel earlier art works composed by male artists allows for the artist’s work to enter into a subversive dialogue with this movement in art history. Understanding Woodman’s relationship to Surrealism as actively dialogic avoids the tendency to legitimise women’s work, in reference to what Mira Schor has termed a ‘patrilineage’ of ‘mega fathers’ that was common to the New York art establishment of the 1970s and 1980s. (37) As Suleiman’s analysis demonstrates, dialogism has since become a trademark tool of feminist art and feminist art criticism, that ‘talks back’ to previous representations of femininity through referencing earlier images, modifying them and reclaiming them in a process of self-determination that defies original misogynist, romanticised constructions. Rather than merely destroying these previous works, a process of dialogue is both affirmative and critical, as it might share some of their aspirations while criticising them on other grounds. (38)

Whether Woodman’s engagement with Surrealism was a deliberate act of feminist dialogism or simply the result of a strong influence on her work is unclear, indicating the seemingly ambivalent nature of her engagement with the movement. However, it is evident that her appropriation of Surrealist images serves a feminist function of subversion that moves or shuttles in-between representations. Such compositions present signature fetishisations of femininity from the oeuvre of patriarchal Surrealism at the same time as the introspective transformative self-determination of Woodman’s own body. They enact a strategic double identification as photographer and model, subject and object. Stasis as one or the other of these positions is defied, creating a unique and powerful interrogation of femininity as representation.

A deliberate subjectivity of indeterminacy may be recognised in Woodman’s photography as creatively strategic, where haunting images of ghost-like angels and spectres as dislocated, transitory and transparent figures create a fleeting femininity that passes between states of subject/object, presence/absence, woman/environment, pain/hope and human/corpse. The ghost or angel haunts the site of representation by continually opening out the boundary between fixed states of being. Despite feminist critique of the dangers of dislocating notions of femininity beyond recognition, the flux of Woodman’s feminine form as phantom woman of transformation demonstrates the power of imagining new possibilities for female identity and existence.

Georgie Boucher

Theatre Studies, Creative Arts