“For me, almost every home is the image of a person”

“My boxes are life’s experiences, aesthetically expressed.” — Joseph Cornell

“The house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories, and dreams of mankind…. It is body and soul. It is the human being’s first world.”

— Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

“For me, almost every home is the image of a person.” — Zofia Rydet

It’s the multitude of images that strikes you first in Répertoire, 1978–1990, the Jeu de Paume’s recent exhibition of photographer Zofia Rydet’s Sociological Record: each rectangle dense with things, their human subjects—women, men, the old, the young, the unwell, the haves and have-nots—all swallowed by stuff. Some inhabitants gaze at us kindly, others look away. Some are pleased, others are skeptical, some simply patient.

But the image that stands out among them is the one of the aged photographer, the bubbe, in the too-big rain cape, her neat blouse and skirt beneath its clear plastic, her white shoes firmly planted on the farm yard’s tufts of grass and mud, intently focusing the Yashica-like medium-format camera she grasps before her bosom, the drop handle of her ladylike frame handbag looped over her left arm.

Zofia Rydet began her Sociological Record in 1978, at the age 67, when her country, Poland, was still a Soviet satellite state. She continued the project into 1990, shooting in homes across more than 100 villages and towns in the Polish countryside, later expanding to include Lithuania, France, Germany, Czech Republic, Bulgaria, and the apartments of Polish immigrants in the U.S. By the time she died, in 1997, Rydet had shot more than 20,000 mostly black-and-white images for the series, making her Sociological Record one of the largest-scale artworks of the 20th century, certainly by a single artist.

Sociological Record previously had only limited exhibition but for a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Warsaw and for an image here or there in a group show in Poland or abroad. Rydet had made some prints of the work, but there were tens of thousands of negatives to go. A Zofia Rydet archive, overseen by Karol Hordziej, of the Foundation of Visual Arts in Krakow, Poland, was established, along with the Zofia Rydet Foundation, and a strong presence built online. From November 2016 through May 2017, Paris’s Jeu de Paume, together with curators Hordziej and Sebastian Cichocki, from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Warsaw, organized and assembled roomfuls of Record’s prints at Jeu de Paume’s Château de Tours. Their exhibit, Répertoire, 1978–1990, included 300 images and, in the chateau’s tower room, Josef Robakowski’s 1990 documentary Interview with Zofia Rydet. Répertoire has closed, but Sociological Record’s negatives continue to be printed, and the already vast collection of Rydet’s work—which includes Sociological Record, her series The Infinity of Distant Roads, and her photo collages The World of Feelings and Imagination, among other projects—continues to grow. As the archive expands, it becomes clear that the vast Sociological Record is both distinct from Rydet’s other photo work and collages yet also very much intertwined.

The idea of Sociological Record came to Rydet when visiting a Polish car manufacturing plant, where she was fascinated by how the workers made personal their small, cookie-cutter cubicles, and how the items amassed within—family photos, rosaries, trophies, tchotchkes— revealed a unique story about the individual. “Each person,” said Rydet, “marked his space with his personality.” Rydet became interested in discovering how people distinguished themselves and “revealed their psychology” through their home and objects. She committed to making a picture of every house in Poland.

Rydet’s methodology in Sociological Record was simple and systematic. She would approach Poland’s modest country cottages, the chata, and knock on the door (“which I think is very important, because I’m asking to be let in,” Rydet said). She’d introduce herself and extend a firm handshake. (She believed this transmitted energy between the giver and the recipient.) “Beautiful! Beautiful!” the photographer would say, and she would walk inside. If the inhabitant hesitated? “She was a terrorist!” her friend Anna Bohdziewicz said. “When people didn’t want to let her in, she used to tell them that she took these pictures for the pope. It was the ultimate argument.” Occasionally, Rydet would take someone along with her, hoping to get them interested in the project, perhaps hoping, too, their interest would continue on when she no longer could.

Once inside the home, Rydet would remark on some object she found moving, a “pearl,” and photograph it. She’d then seat the inhabitant with the wall as a backdrop and shoot—always from the same distance, with the same horizontal frame and camera angle, with the same wide-angle lens and mounted flash and the subject facing forward. Sometimes she’d use her Yashica Exacta, most times a 35mm camera. Initially, Rydet shot the subject only against one wall; as the project progressed, she’d shoot against each of the cottages’ four walls. Her reward came after she made the picture, when she’d sit with the inhabitants and drink up their stories and simple wisdom. “My whole philosophy with regard to life was turned upside down,” she says in Robakowski’s documentary.

Yet despite her focus on the countryside and her uniform approach to each photo, Rydet’s Sociological Record goes beyond ethnography or mere cataloguing. It gives us a picture of Poland under communism that is not monolithic but instead striated by economic standing and religious belief, each inhabitant precisely captured amid their possessions (or lack thereof). Despite Rydet’s grandmotherly appearance, and her more or less self-taught approach, she was far from innocent in what she was attempting to say with her work. The fact that the pictures include both the very poorest of subjects along with the wealthiest and the religious made her homes transgressive: Her even-handed treatment of the subject was socialist, but what her images reveal is not.

“The house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories, and dreams of mankind…. It is body and soul. It is the human being’s first world.”

— Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

Like a hermit crab’s shell, each home reflects its inhabitants’ life journey. Each household in Sociological Record offers a unique story told by its stuff.

Rydet was born into a bourgeois family in Stanislawow (Stanislaw), Poland, in 1911. Her brother, Tadeusz, to whom she was close, was like her father a lawyer. In his free time, Tadeusz pursued photography. Rydet, creative and visual leaning (she loved painting), wanted to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krackow, Poland; instead, in 1930, she went to a girls Economic School in Snopkow. In 1934 she worked in her brother’s travel agency in Stanislawow, and was inspired and mentored by him to take up photography. She made a series of photos on the children from Poland’s Hutsul village. She graduated from school, returned to her brother’s travel agency, and then later worked with a photo agency. In 1938 she purchased her first camera, a box. The war came on; Rydet’s photo projects were put on hold. Stanislawow became annexed by the Soviets and Ukraine in 1939, then occupied by the Germans and the Hungarians. The family that year moved from occupied Stanislawow to Rabka, Poland. After the war, Rydet left for Bytom, Poland, to open a stationery and toy store.

At the age of 40, Rydet purchased the Exacta and photo books and set up a darkroom in her home. She became a member of the Gliwice branch of the Polish photographic association. In 1959, Rydet saw Steichen’s exhibit Family of Man. It was a pivotal moment that made her realize that photography possessed not only an aesthetic function but also a social purpose.

Rydet was driven. In the late 1950s and early ’60s, the photographer took part in exhibitions, in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Portugal, Japan, Australia, and India. The Polish government at the time was constrictive with its citizens yet more liberal with its artists, and encouraged them to travel outside the Eastern bloc.

In 1961, Rydet had her first solo exhibit, Little Man (Maly Czlowiek), which included more than 150 of her images of children. The show was a success and was seen in Poland and abroad. She was accepted as a member of the Association of Polish Art Photographers (ZPAF) and began a dummy of a never-published book on the countryside. In 1962, Rydet closed her shop and devoted herself completely to photography. She moved to Gliwice and became a photo teacher at the Silesian University of Technology. Her work was exhibited in several shows; another series, The Passing of Time (Czas Przemijania), black-and-white portraits of older persons, some more more formal and others a bit abstracted, was exhibited in 1964; and in 1965 the photos from Little Man were published in book form. In 1967, she laid out the preliminary idea for Sociological Record. In 1976, she won the highest distinction from the International Federation of Photographic Art. She started work on her series The World of Feelings and Imagination and The Infinity of Distant Roads. In 1978 she began Sociological Record, working continuously, through the crushing of Solidarnosc, in the early 1980s, through martial law, and the fall of communism in Poland, in 1989.

Rydet’s Sociological Record can be divided into several sub-categories. There are portraits with TV sets, portraits with religious iconography, portraits with pop-culture stars, and portraits with political figures. There are the professions, the families, the infirm, and the women in doorways. Some pictures are bleak; some are ordinary; some are revelations.

The Jeu de Paume’s lovely, compact catalogue for Répertoire opens with a Diane Arbus–like shot: Two young boys, twins almost, with slicked hair, sit shoulder to shoulder against a single patterned curtain panel, which is bordered by patterned wallpaper and a window. A large, traditional Hummel-like figurine, its face the same shape as the boys’, is propped on a table and large doily, its head tilting toward the children. A modern model plane hovers overhead. To the boys’ right is an extra-large television set (especially by socialist standards), a porcelain dog seated on top, while to their left a curious, small dark-skinned girl doll is seated on a chair.

In another photo, a young girl sits in the kitchen, in front of the door frame, prim in her blouse and knee-highs, her hands folded in her lap. She’s also flanked by a big TV, on her right, while a large owl perches, wings spread as though taking flight from the top of the cupboard, to her left. A Persian rug lies on the floor, a modern lighting fixture on the ceiling. The doorway behind the girl extends beyond to a doily-and-plant-filled room. The plant theme echoes in the picture’s carpet, curtain, and tablecloths.

On the opposite page, a young blond man, perhaps a teenager, sits on a stool grasping his knee. He leans against the door that frames him, whiskey bottles aligned on the lintel above. He is clearly at home amid his motorcycle helmet and Osmonds poster, his small room papered in posters and signs, its parquet floor beneath his feet.

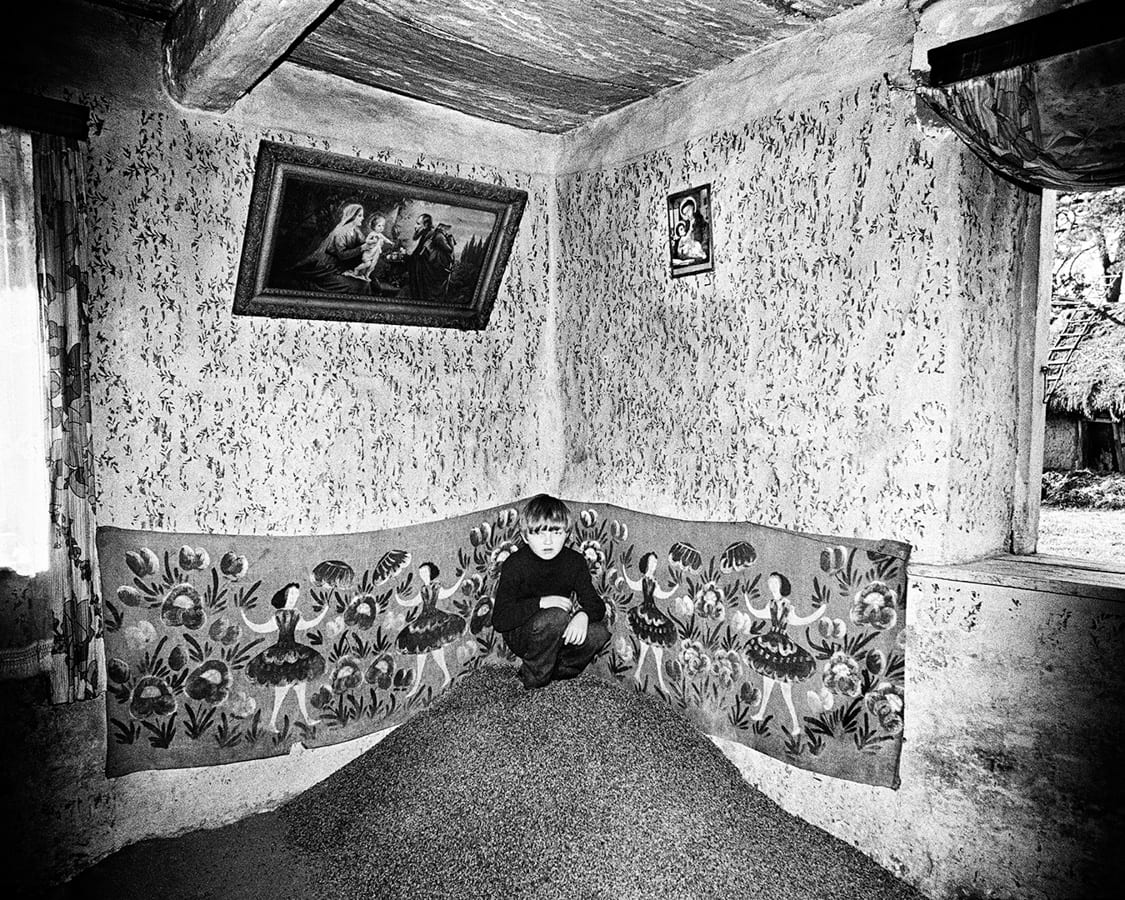

In contrast, a young boy crouches in a corner in a room without furniture, its ceiling bare but for the beams. He sits on what initially appears a pile of sand but is likely the carpet flooring, while folkloric fabric runs the length of the wall behind him and religious pictures hover above.

Elsewhere, a young woman is seated on the floor of her home, her arms wrapped around her knees. A bed abuts a plaster wall that separates it from the stove, its walls and ceiling crumbling. Her feet are bare, her big toes blackened, her cooking pots few and modest—yet she seems almost pleased to have her photo taken.

In a wonderful image, a sort of former soldier, sword in hand, stands straight against the wall in his uniform and laced boots. His cement-block stove adjacent mirrors the rigid uprightness of his back. From the ceiling, old photos and old furniture hang like stalactites; the wall is covered with iconic portraits—George Washington, John F. Kennedy, and Jesus.

Another picture features a couple seated in separate chairs, a smaller chair between them, against which a big blonde doll is propped, a large plant seeming to sprout from her head. A rug with a plant-like pattern extends beneath their feet, and a television on a TV cart sits frame right.

In some shots, grown men sit on too-small stools or chairs, lending a comic effect to their sometimes bleak surroundings. Plants and large birds, wings and tails fan over subjects seated beneath them.

Women stand in their doorframes, outside their homes, some constructed of large wood planks with thatched roofs, others cinder block, and yet others adorned with flowers and ornate wood carvings. There is a shot of Rydet seated center frame amid her many books.

Several of the subjects feel curiously isolated and alone. A young girl, her knees covered by her skirt, short puffy sleeves on her shoulders, seems to sink into her upholstered chair. A panel of fabric sluices the wall behind her, the carpet segments the floor beneath her. A telephone sits to her left. There is a small bureau of family photos, though the emptiness of the chair beside her and of the walls make her seem almost an orphan.

The title Sociological Record was bestowed by Urzula Czartoryska, but Rydet always found it too academic. It is also a bit misleading—perhaps even purposely so, considering Rydet’s images challenged the all-prevailing myth that all were equal under Soviet-style communism. Perhaps the title itself was an umbrella whose radius circumscribed the project’s breadth and focus, while also affording Rydet some shade from authorities, who might deem the diversity depicted in her pictures a bit dangerous.

Rydet’s approach in Sociological Record, walking into random chata, worked because of the Polish countryside’s tradition of “Cyzm chata bogata, tym rada”: its humble, open-door hospitality. (The phrase roughly translates to: “All we have is at your disposal.”) The state glorified the simple working man embodied by the country folk. Yet it preferred not to focus attention on the distinct values, pride, and individuality of the Polish countryside—which was also a bastion of Catholicism when religion was seen as resistance under communism and worship an almost revolutionary act. Compared with the idiosyncratic country cottages, Rydet saw the cities’ standard “modern” housing, the ones to which Poland relocated a good number of its population in an attempt to redistribute money and possessions under the Soviets, as “boxes with flat roofs.” In contrast to her merely walking into country homes, Rydet was only able to enter city homes by invitation; once inside, she described the people and their possessions as “dull.”

Rydet’s photographs for Sociological Record were singular. They strayed from the state-sanctioned socialist realism, with its idealized socialist content and forced optimism. In addition, the Polish photo association was mostly male and their work largely conceptual. Rydet stood apart as a woman, a humanist, and as a maker of documentary images.

Yet Rydet’s work was not without precedent. Parallels can be drawn between Sociological Record and Yugoslavia’s Black Wave film movement of the 1960s and ’70s, and in particular in the work of filmmaker Zelimir Zilnik, with its focus on people from the fringes; similarities are seen between her work and Joseph Cornell’s, and with Arbus’s off-kilteredness. And though Rydet was self-taught and mentored by her brother, Tadeuz, she was not a naif. She traveled and shot internationally, during which she was likely exposed to other artists and movements—if she didn’t purposely seek them out. Her bookshelves reveal a woman who was well-read. She took photo courses, read photo books, and printed her own work.

That is, the images for Sociological Record were not haphazard or a hobbyist’s but highly informed and thought-out. Like the self-taught assemblage artist Cornell (who, similar to Rydet, had no immediate family of his own and had a preference for the working class), the photographer was intent on capturing life’s experience within a strict frame. Like Cornell, Rydet had a strong hand in creating her human tableaux, arranging the elements in the “mise-en-scène,” as she referred to it. (That Rydet even used the term mise-en-scène is evidence of her sophistication and exposure, both to other cultures and mediums.) Her unpublished negatives reveal that objects were moved and rearranged—the religious icons, stuffed birds, makatka (decorative tapestries), television sets…all purposely placed to make a statement. In the 1989 documentary film The Infinity of Distant Roads: Zofia Rydet, the photographer meticulously directs the elements in her camera frame, making sure to capture the sign SOLIDARNOSC behind her human subject, exacting in the placement of his hands, which are deformed.

“My boxes are life’s experiences, aesthetically expressed.” — Joseph Cornell

Rydet describes making her images like writing, its elements like letters she would arrange into a whole. (Rydet was influenced by literature and said Steinbeck’s Pasture of Heaven was a “must-read,” and Steinbeck’s plain-spoken description of the diverse lives and dashed dreams in the book’s Monterey, California, valley setting resonates in Sociological Record.)

Rydet’s framing and placement (and even editing out) of objects and inhabitants—who in their almost-uniform looking into the lens, and who under Rydet’s direction became objects themselves—were both artistry and commentary, as they were for Cornell. Her photos were documentary, but they were clearly not pure documentation, nor were they simply reflexive responses to capturing history. The photographer’s mise-en-scène was a setting of the stage, an act of investing the image with narrative and the inhabitants’ history, hopes, memories, disappointments, and contradictions—all embodied in their individual and collective things.

Rydet was not only exacting in her placement of her subjects’ possessions but also in her frame-within-a-frame positioning of the homes’ inhabitants: in a door frame, in front of a window frame, against a panel of fabric or patterned curtain, or between two windows, themselves framed by pulled-back curtains. Her frame-within-a-frame aesthetic extended even to family photos, which Rydet shot, the object minus the subject, simply propped against a sofa or hanging on the wall.

These mise-en-scène interior assemblages were also an extension of Rydet’s photo collages in The World of Feelings and Imagination, on which she worked for five years (it was published as a book in 1979), their spiritualism, sexuality, emotion, obsessions, and tension a counterpoint to any “sociology” of Sociological Record. (During the later and last years of her life, too weak to travel and roam the country to make photos for Sociological Record, Rydet again turned to making photo collages.) Like Sociological Record, World of Feelings also included subcategories, or chapters: Love, Maternity, Waiting (with its placid, masklike faces), Mannequins, Sentimental Ballad, Solitude, Phantoms, Menace, Sadness, Transformation, Hope…. These densely packed photo collages present an otherworldly and out-of-context mix of wild beasts and sleeping cherubic babies with lush vegetation, burning candles, angels, mountains of breasts (literally), ancient monuments, strange creatures, foreboding landscapes, headless uniformed figures (similar headless figures are also prominent in the renown Polish sculptor Magdalena Abakanowicz’s work), a bride in a doorway, her face obscured by her veil, and Dali-esque draping gloves. (The influence of surrealism on Rydet’s work is something else she shares with Cornell.) Sometimes erotic, other times kabbalistic, the work shows “a world that threatens us from all sides,” Rydet said, “and the only thing that saves us is love.”

In one image in World of Feelings, a disturbed-looking man in a nightshirt with a dachshund seated in his lap looks upward and askance, his lips parted; behind him is a cuckoo clock and the miniature figurine of a deer is aligned with others on a radiator. The man, his expression and the contorted angle of his head unchanged (was he caught in shock or in mid-speech?), appears in several others pictures in this series. Elsewhere, detached mannequin heads lie against a board, with long sharpened knives lined up below. The field surrounding them is fallow and strewn with straw. Another shot, in Solitude, reveals ominous, oddly shaped hooks, while an older man (with a Hitler-like mustache) peers through a rectangle in the upper right of the frame. In a shot from Menace, naked, hairless female bodies cross a harsh landscape. In other pictures, the mannequins have clearly visible numbers and letters across their ribcages, while in others they are missing arms.

Rydet is no longer here to comment, but given all that the photographer lived through—World War I as a very young child and World War II as an adult; that her country and hometown, Stanislawow, were occupied and attacked by both the Germans and the Soviets, under which Polish lives were upended and many eradicated; and that in 1941, Stanislawow was the site of an infamous Jewish ghetto and the Bloody Sunday massacre, when some 10,000 to 12,000 Jews were shot dead, it’s no surprise that one chapter of World of Feelings is titled Extermination and the images within it more macabre. Rydet’s Little Man, with its complex (rather than innocent) images of childhood was itself inspired by the writing of Janusz Korczak, a Polish doctor and children’s author who was a victim of the extermination camps. That is, perhaps her urgency to memorialize the living was due to Rydet’s intimate familiarity with how fast and irrationally worlds and people could vanish.

In the film of World of Feelings, compiled by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Extermination opens with a somewhat grotesque figure in a black coat (a figure that appears in other Rydet images, as well), his sleeves tattered, his face surrounded by black birds, his hands over his eyes. It’s with this head, Rydet said, that she was finally able to say what she was searching to express with her photos. She said arriving at this image was one of the happiest moments of her life.

Rydet described her compulsion to photograph to a friend: “I keep getting new ideas. I need to take photos immediately. It’s like an addiction, like vodka for an alcoholic.” She was said to work in the darkroom through the day, coming out only briefly for lunch, claiming that making prints was like opium: “I breathe it in, and I forget about everything else. It works like opium for me. I feel so rich being able to stop and save all parts of life that move me.”

“Death’s doors” as she referred to them, were a pervasive presence in Rydet’s mind, a reminder of all that she needed to complete before she passed through them. Photography became her way to fight mortality. As she tells a subject she’s shooting in Distant Roads, “I won’t be here, you won’t be here, but your pictures will be.” Later in the film, she says, “I want to say why I began to do this…. I extended their lives!” “I still have so many plans,” Rydet said, “and not quite enough living left to do…. A day when I don’t photograph seems wasted to me.” Rydet was propelled not only by her intoxication with photography, but also by a demanding inner force not unlike Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable’s: “I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

Yet despite Rydet’s all-consuming awareness that time, and her time in particular, was finite, and that loss and death were constant companions, the photographer was far from morose; she was in fact quite innervated and animated, even as the film Distant Roads captures her close to the end of her life. Making pictures was clearly Rydet’s means of preservation—of herself, of disappearing worlds.

Rydet was determined that her images, and the people and worlds they encapsulated, would survive, going so far as to safeguard her work by sending some of it abroad. “I will leave something behind, assuming the world doesn’t cease to exist,” Rydet said. “Just to be safe, I will send my work to various places—here I do not scrimp. If the bomb falls here, maybe it won’t in Moscow or in Rome.”

With special thanks to the Jeu de Paume, Annabelle Floriant, Karol Hordziej, Fabienne Ayina, Magdalena Santos, and Zofia Augustynska-Martyniak.

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Marlaine Glicksman. Images @ Zofia Rydet.)