It’s estimated that there are about 150 million asteroids and small planets – near-earth objects or NEOs – in earth’s solar system. They are rich sources of so-called ‘strategic metals’ – platinum, gold, lithium and other rare earths used in the manufacture of electronics – as well as more common ores like nickel and iron. Mining these materials from asteroids would put an end to the costly and destructive business of digging them out of the earth’s crust.

But only a tiny fraction of the resources mined in space will be sent back here – most will be used to push further into space, in a recursive cycle of extraction, exploration and off-world development. It’s estimated that the main asteroid belt in our solar system contains hundreds of billions of dollars of mineral wealth. Exploiting these resources will make a few people unimaginably wealthy. As well as technological innovation, offworld initiatives like these require a new form of capitalisation: an economic infrastructure designed not only to support the development and deployment of physical assets, but to deal with the inevitable collapse of terrestrial markets as once-scarce resources suddenly become abundant.

“Asteroid mining might create a new Arcadia here on earth. But it might also bankroll the creation of gilded playgrounds in the sky, leaving behind a planet full of ruins and redundant humans.”

In August of 2017, Luxembourg became the first European country to pass legislation allowing private companies based there the right to exploit off-world resources. Along with the US, Luxembourg is transforming itself into a hub for what is set to become a multi-billion-dollar industry. Moving most of our mining industries into space – replacing the chaos of open-cast and deep mining with precision extraction performed by robots – would leave a cleaner, greener earth for us to enjoy, or so the literature tells us.

But innovation on this scale has a way of leaving a trail of obsolescence in its wake. Nothing decays in the oxygen-poor environment of deep space: fleshy bodies and earthbound industries are vulnerable and crude compared to the immortality of celestial machines. Asteroid mining might create a new Arcadia here on earth. But it might also bankroll the creation of gilded playgrounds in the sky, leaving behind a planet full of ruins and redundant humans.

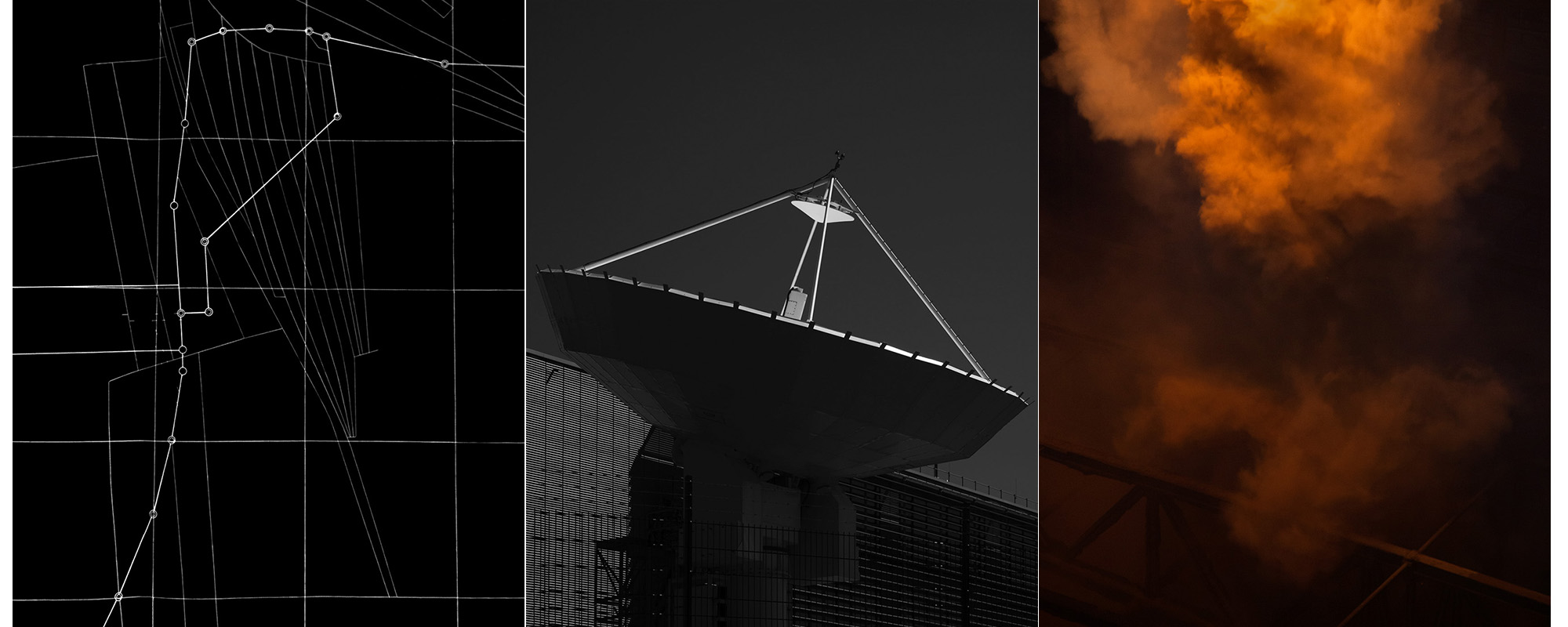

Ezio D’Agostino’s NEOs is a reflection on the distance between the subterranean and the celestial, and the complex instruments we’re building in order to bridge it – a speculation on the relationship between recent pasts and possible futures. The first image in the book looks like a flock of stars scattered across a deep black galactic void. But they’re not stars, they’re the residue of calcium carbide combustion, produced by the open flame of the carbide lamps long used to illuminate the darkness of iron mines. It’s an equivocal image, captivating but also dark and duplicitous. In NEOs, things are rarely what they seem – the heavens are made of ash, maps of underground mines resemble star charts; the slagged remnants of earthbound industry look like alien spacecraft dropped from the sky. Other images are almost algorithmically precise: clean-cut hypermodern architecture, the repetitive geometry of its surface hiding … what? Bars of gold or covert research facilities or agile financial instruments writing our future in machine language. D’Agostino’s photographs borrow the alloy/silica sheen of these structures, their silvered surfaces as estranging as frozen metal.

“NEOS is a book of strange prophecies, portents of a future where there’s a price on the stars and the skies are heavy with space junk.”

An unidentified hand holds up a heartbeat sensor used to detect the presence of invaders in the Freeport – an ultra-secure storage facility housing works of art and other valuables. It’s the only image of a human body in the book – a fleshy anachronism. Elsewhere, human presence is signalled only by the markers of its fragility: boots, gloves, and helmets worn to shield frail flesh from the extreme heat and toxicity of smelters and blast furnaces. Pitted steel surfaces, fractured ground and slabs of obsolete machinery are relics of an industrial past in monumental meltdown, and an outmoded form of capitalism based in human labour.

Endless expansion is contradictory and impossible. But we persist in thinking that it can work, that new economic instruments might somehow escape the logic of terrestrial capital in the same way that machines can evade the effects of time and gravity on the body itself. The distance between past and future, human and machine is parsed here along the stark lines of the archaic and the anticipatory – the middle ground between the two burned to ash in the scorching heat of rocket exhaust.

NEOs is a book of strange prophecies, portents of a future where there’s a price on the stars and the skies are heavy with space junk. It’s unsettling to think that we might be building a future without monuments – divinely invisible instruments and fantastic machines that won’t leave a trace of their cultural legacy here on earth. D’Agostino’s photographs – elegant and meticulous, but also obscure and cryptic – are allegories for the speculative character of this whole enterprise. It’s crystalline and elegant and terrifying: machinarum in deos – machines become gods. It looks like science fiction and maybe it is. Beautifully designed by Nicolas Polli, with a smart essay by Andrea Lorena Soto Caldéron. Get this one before it sells out.

Ezio D’Agostino

NEOs

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Eugenie Shinkle. Images @ Ezio D’Agostino.)