“The title Moksha is a Sanskrit word for liberation or emancipation and for me relates not only the freedom gained with independence from the colonial rule but alludes to a freedom of the mind, a spiritual freedom of unlinking oneself from the bind of oppressive states of existence.”

The postcolonial condition is one that is uprooted and transnational, spanning global geographies in a deterritorialized domain of interconnectedness. Where the once imperial powers enjoyed extended sovereignty after seizing overseas territories, establishing borders, accruing resources and wealth, exporting Western law and order, implementing governmental structures for administration, supplanting their cultural sensibilities and refinement, the postcolonial order was to largely keep modernity intact and replace the colonizer’s governance with democratic or autocratic indigenous regimes post-independence. Political struggle and civil unrest often ensued while attempts were made to establish a new social order. After the retreat of the colonizer, this can be seen the world over as the fight for power between local political oppositions, ruthless and violent, in many cases forced displacement, exile and global migration. The postcolonial subject is one that finds themselves either fortunate in the new regime or in a position of precarity having to survive and ultimately find security and stability elsewhere.

The legacy of colonialism complicates because while there is the imagined freedom of a new national identity, the remnants of pre-colonial ideologies together with the colonizer’s instilled ‘divide and rule’ tactic, reinforces inequalities and inherited binary moral positions: ‘us and them’, or ‘good people and bad people’. Despite efforts towards socialist or liberal politics, radical emancipatory and rights movements, much of this remains in place today. One oppressive order is replaced by another. Talk of finding liberation today is not the violent revolution that Frantz Fanon calls for in The Wretched of the Earth, but a contemporary version of decolonization: a promise of structural and narrative reform whilst some engage in discrete acts of resistance, agitation and antagonism that disrupt the power play of actors seeking to maintain their position in control. Plans to overthrow the existing structure (with a new “colonizer”) have shifted towards the formation of collective action against the poison of inherited beliefs and the ignorance of conscious and unconscious privilege.

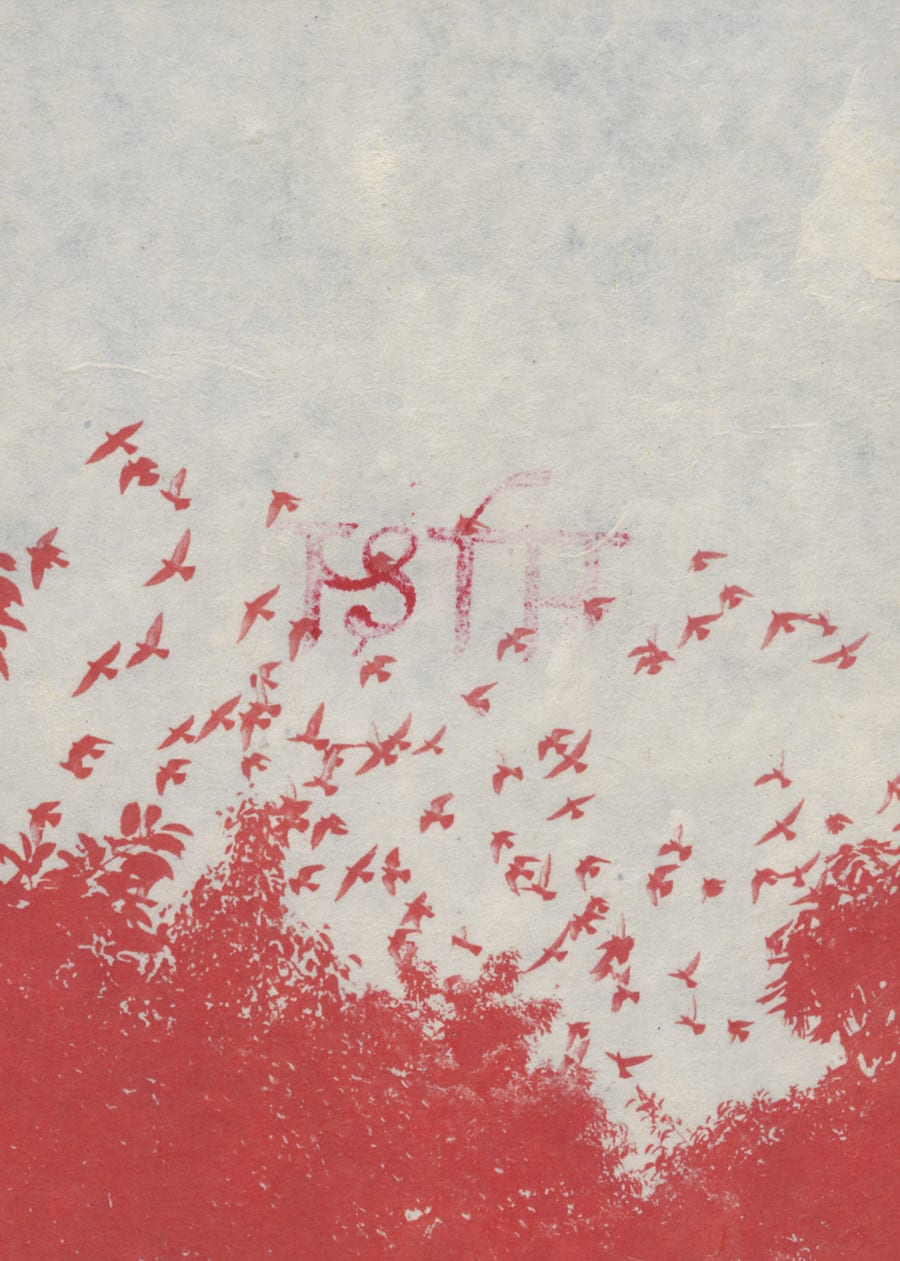

It was Rohan Thapa’s Moksha which prompted some of these thoughts as I wondered if its image economy could provide a backdrop in which this conversation could begin to emerge and unfold. Thapa’s self-published ‘zine’ consists of a package in which 66 loose printed pages are placed in what is like an old, paper envelope passed down from a South Asian grandparent who might have been around to witness the effects of post-independence first-hand. The title Moksha is a Sanskrit word for liberation or emancipation and for me relates not only to the freedom gained with independence from colonial rule but alludes to a freedom of the mind, a spiritual freedom of unlinking oneself from the bind of oppressive states of existence.

“Plans to overthrow the existing structure (with a new “colonizer”) have shifted towards the formation of collective action against the poison of inherited beliefs and the ignorance of conscious and unconscious privilege.”

In the context of this zine, Thapa is open to its interpretation; evaluate, re-sequence and re-distribute these pages how you see fit. That the artist has foregrounded the text as Sanskrit and not English or in the language of his current national residence, Spain (although translations are present) proposes an attitude to the subject matter that is not Western or European but of the Indian subcontinent. The pages syncretically depict images taken from various sources and places. The index tells us Nepal, India and even Spain feature as geographical sites and yet these are here collated, caption-less into a set of symbols, perhaps standing in for states of both freedom and oppression. Without a fixed narrative, what I picked up is a relationship to a colonial past and a troubled present, there are depictions of labor, protest and violence, figures conveying a sense of inner turmoil. Could these images be a reference to the wounds and trauma of the postcolonial struggle?

The pages printed in red ink with the Sanskrit stamp of Moksha, written as: मोक्ष, evokes the blood shed through conflict. The blood here is rich and bright, it stains and soaks the pages, just like real blood but when it is fresh. There is an immediacy about this, although there are scenes from the past, there is a rawness. Thapa reopens the past as a wound or a scab that has not healed but is the cause of an underlying inner pain or malaise, ignored with the hope that it will pass – but it does not. Yet, this blood that emerges is a familiar unifying symbol, the fluid of life that we all share, a visceral reminder of what holds us all together as beings on this earth. It courses through us and out. Thapa’s Moksha is both blood spilt and the blood that flows, the realisation of inner conflict and the biological transport by which all humans relate as one. As these images show, to reveal these wounds is necessary, if at least to make visible, scars that should no longer be ignored.

This postcolonial affliction is one that still grasps many (myself included) with its latent and insidious grip on the individual and collective consciousness. Thapa’s Moksha for me is a decolonial aesthetic that creates an imaginary space of struggle. It is a struggle for freedom against the colonizer’s cancerous mindset that continues to abuse and reinforce its power. I think it is within this imagined space that we can either be kept under or find forms of resistance and catharsis.

Self-published

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Sunil Shah. Images @ Rohan Thapa.)