“And so many great books of history will be written about the same castle with different bleeding fingernails clawing at its porous surface and every ending will always be the same – you will not be defined by this edifice, you will not be defined at all”

Complications arise from the insistence that a façade of structure give value to meaning. What lies between the discipline of the frame and the hypothesis conducted as an after effect of its viewing leads the singular pattern of thought to various places fecund with possibility and intrepid with personal narrative. It is only when relativity and enforced and institutionalized meanings of the image coalesce that trouble begins. Cold smooth stone with rigid lines of deep cut marks carved deeper by the insistence of the sun’s unholy glare shuffle in the mind, their potential like a deck of cards in the hands of a one armed and tired magician, each singular potential card bearing the same weight and number of the one opposing it. The value shuffled in parts has no larger value than if combined and displayed to the intended viewer who, by no fault of her own, will read a completely different set of numbers and may inquisite as to whether the figure behind the hand holding them is the catalyst for their being or simply a debilitated oracle searching for suggestions or affirmations for himself in the repository for their enforcement of meaning. “Can we agree”? “Will you agree with me”? “Is this your card”?

Prague, Warsaw, Athens, Madrid-populaces swelling with the “classical” culture, which western peoples have taken as their own image in agreement. Their image is sadly without motion and is but a larger fiction to the stationary impediments or rudiments of cultures dispersed about such grand cities. The forlorn Jewish cemetery, the cargo doors of a not so ancient and now institutionalized concentration camp, the Temple of Olympia with its cylindrical ribs deteriorating under the exhaust of new and lesser gods-all stand stoic and static as the ants swirl about their great stillborn girth and bask resplendent in their small consolations of enforced unity. This impoverished idea was shaped by the potter’s hand during the Mycenaean period-it was an epic so grand that it had to be buried twice. It was also shaped in ghettos teaming with life and with energy, combustible in the face of an adversity so great that it could have been registered as the saddest chapter in a book of human thermodynamics. It is the chapter in which pages have been torn out by various keepers of various infirmed castles.

All castles will eventually come under siege. It is a simple equation really. A number of years brace themselves upon the packed stone walls of what can never be truly impenetrable until loose sediment rolls off the head of the dreaded other below who clamors upon it insistent, but whose weak face is drawn tight in a feeble attempt to gain victory over its magnitude and make it his or her own. And so many great books of history will be written about the same castle with different bleeding fingernails clawing at its porous surface and every ending will always be the same-‘you will not be defined by this edifice, you will not be defined at all’. And with that, the anguish between the perceptions of the static image towers so great that before long it wavers and plummets quickly into the quagmire of its possibility to be named and recognized by an errant history framed.

“The castle, which controls the populace, does so through an absolute production of its image. It is a tale in which plebian might is as disorganized as any contemporary parallel for leading a resistance against the juggernaut who rules by fear and an unethical chess game between the citizens and the tyranny of the castle’s own image ensues”

Federico Clavarino’s “The Castle” is but one icepick in the spine of existential image making, but it is colder than most. Fragments and facades of an ever changing and undulating realm of images are questioned for their sanctity as well as their heritage/cultural potential. Formalism weighs heavily on the photographs, but why should it not? Formalism is the basis for perceptive geometry and idolatry. There is also a loose quality about the edit due to the locations of the images and the push and pull between the books title, which would formerly have been indicative of Kafka and perhaps Prague. Having not read the Kafka novel itself, I had a quick look and was unsurprised to find that themes of existential dilemma, alienation, solitude, and some mild form of paranoiac response by way of government are listed as narrative devices in the book, which further was Kafka’s last and unfinished novel. It is a tale in which the protagonist enters a village along his journey that is governed, like an indentured servant on whole by the tyrannical seat of the castle perched above the town. The castle, which controls the populace, does so through an absolute production of its image. It is a tale in which plebian might is as disorganized as any contemporary parallel for leading a resistance against the juggernaut who rules by fear and an unethical chess game between the citizens and the tyranny of the castle’s own image ensues. It feels familiar. This makes sense in many ways when we examine Clavarino’s work, notably the images of statues, their imposed and recognized postures of European culture and their weathered facades culminate in what could be a clever metaphor for the democracy we are challenged with today. Shadow cabinets, shadowy men, shadow banking-all power lies in the hands of the shadow. We blindly follow its call because the undefined image of itself is greater than the will of our collective citizenry to thwart its hold and make it recognized with impunity.

Further to this, Clavarino’s images remind me of high Modernist and Surrealist images from central Europe in between the wars. There are elements of Man Ray, Brassai (some images bordering on renditions of involuntary sculptures) Kertesz and a nod toward a few other masterful artists-Dora Maar perhaps.

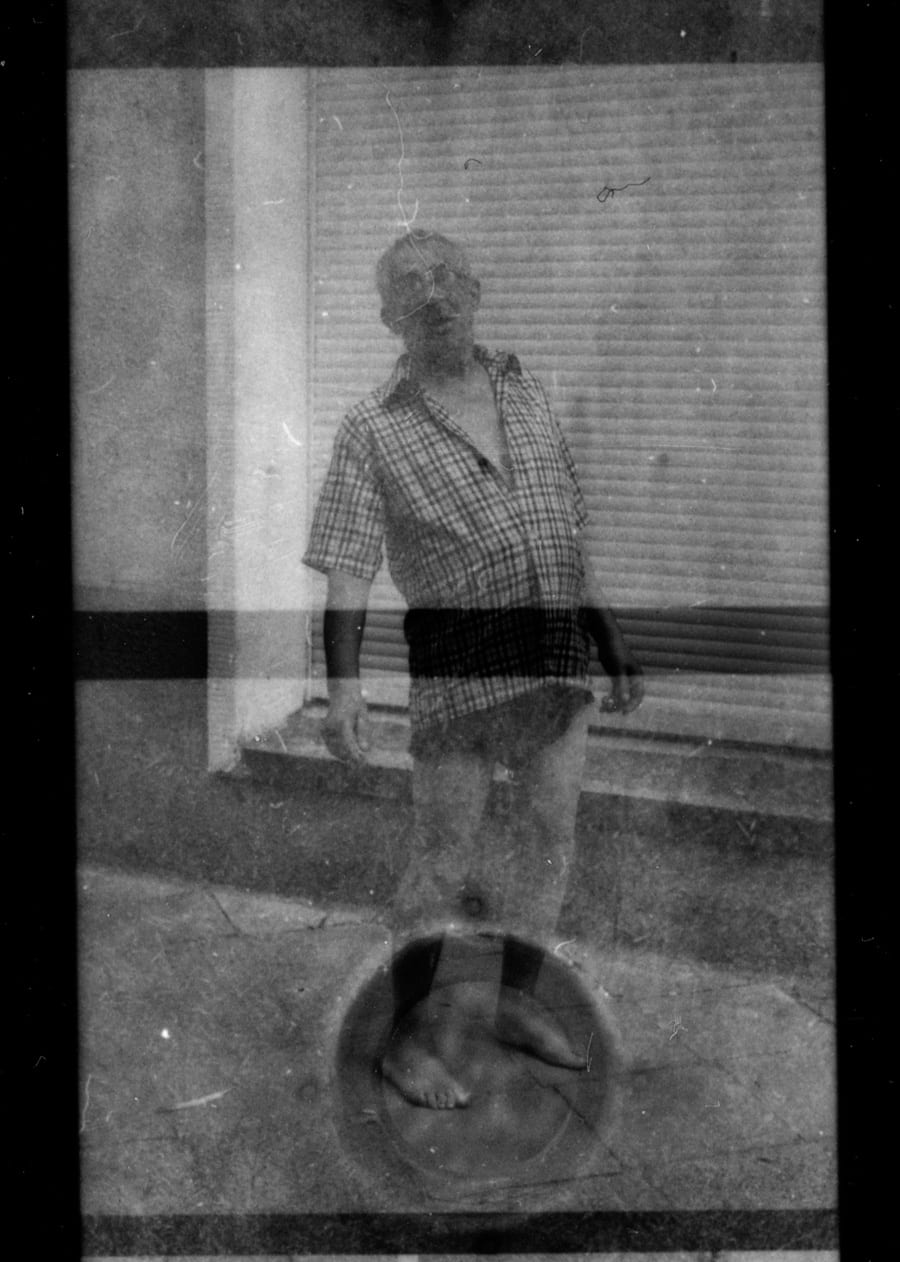

The book begins also with a series of film ends and double exposures that depict a man walking through the streets of Warsaw to which Clavarino in the end of the book employs a gesture of empathy towards the subject, though after the film was developed, in which he recants…

“One day I was walking around Warsaw, my camera in my hand, when I saw an old man coming towards me. He looked somewhat lost, and walked with a limp. I stopped as he slowly went past me. I could hear him breathing very heavily. Shortly after I felt really bad for taking those pictures. The following say I travelled to Krakow and then on Auschwitz-Birkenau…..”

“It was only when I came back and developed the film that I noticed that while changing it in Auschwitz, I had inadvertently loaded the Warsaw roll into the camera, thus exposing the pictures I had taken inside the camp on top of the ones I had taken around the city (Warsaw).”

There is something interesting to speak about here, perhaps in the nod to post-war Europe, but also about how images attach themselves to each other through error, serendipity or editing. The language of empathy abounds. Clavarino is somehow embarrassed of himself for photographing the man in his sad and disheveled condition. Perhaps he feels he is a voyeur. Yet in the same instance, Auschwitz, as the most powerful specter of WWII, has become a grand macabre spectacle for which he and other photographers flock by the dozen to bear witness to the atrocities of WWII and yet, though I am sure Clavarino understands the implications, the power of the Auschwitz image here is controlled by history and the spectacle that it has become post-event or post-real time. As a subject, it exerts certain autonomy over its monumental structure. It has been codified by politics, history and genocide to do so. Whereas the old man on the streets of Warsaw, the plebe as he is has no control over his image and is instead now governed by Clavarino and his camera, even if by chance. He is now circulated with a new meaning by the accident of Clavarino’s image and is being applied to Auschwitz and as the result is thus absorbed into a new meaning within the structure of the paradigms mentioned above-politics, history and genocide. These categorical assertions now govern his image, making Clavarino’s card trick all that much more potent, if unintended.

Further to the conversation of ownership of an image or its “weight” is what Boris Groys might have considered as the possibilities of images that exist in the “realm of the profane”. Groys has put forward that culture and its products become sacred when they are institutionalized. They become recognizable. He describes their characteristics as being valorized by these archives and institutions in his book “On the New”. To cross an image of a concentration camp, which has in a very strange way has become valorized by the academies of history with an image of a man that seems unimportant to the cultural place within institutions is to search for the new between both realms of the institutionalized sacred and the mundane previously un-documented or un-valorized realm of the profane. In no way am I promoting this as a reach into the new, but I am questioning by way of Groys what it means to conflate both realms as Clavarino has done. It’s a small point and perhaps reaching, but within the book other examples play between the quotidian image and the image that has been previously valorized-the sculptures in particular.

The book is loaded with possibilities as great photography should be. It is monochrome and therefore limits the distracting factor of a “nowness” of color images. Color photographs, though rarely spoken about, have the possibility of defining epochs, ages, and even decades. When it is muted for monochrome, it does two things. 1) It harkens nostalgia 2) Contrarily, it opens the box of ageless possibility. In using black and white, Clavarino with his modernist and surrealist tendencies, does not simply ape an aesthetic of the past, but employs a contemporary drive to assert pressure over the images to perform in a certain manner without ascribing them value as mere aesthetic exercise. The images are restrained from becoming comic emulations of the categories of modernism and surrealism and feel unashamedly his own, but they have been contextualized by the title to offer the possibility of reference, though not absolute as to where his audience may meander through an invented photographic history to find an existential narrative for his contemporary images. This is an investigation that we can only achieve through our own eyes with our own histories and our relationships to them. The absolute of one as it were. Though references are aplenty, it would be the aim of this work to reflect inward and draw conclusions and projections from the stringy fibers of one’s own being and persona and take on history and current political climate in which one finds themselves. Highly Recommended.

Dalpine

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Brad Feuerhelm. Images @ Federico Clavarino.)