“That process of walking every day for long periods of time, you slow down, you start to really observe how your mind’s working, get a different sense of the connection between mind and body and your surroundings. It was a very physical process, and the pace was quite meditative, so I wanted to make a series which just used landscape images in book form to suggest this sense of an internal journey.”

In the West, our understanding of landscape is based around strategies of spatial organisation, such as linear perspective, that date back to the Renaissance. Our experience of landscape is heavily conditioned by these strategies – we tend to think of a landscape as something that is seen rather than felt. For those working with conventional lens-based technologies, this bias is difficult to avoid. For the past several years, Irish photographer Paul Gaffney has been investigating different ways of experiencing and representing landscape. We spoke in London in November 2015.

ES: Lets begin by looking at some of your earlier work – can you talk a bit about We Make the Path by Walking?

PG: We Make the Path by Walking was made over the course of a year, in 2012. I was interested in the idea of long distance walking as a form of meditation, and immersion in the landscape. I’ve been into hiking for quite a while, and I’d started doing some meditation courses while travelling in 2008, which were in themselves a really intense personal journey. Shortly after that I went to Spain to walk 800km of the for the first time. That process of walking every day for long periods of time, you slow down, you start to really observe how your mind’s working, get a different sense of the connection between mind and body and your surroundings. It was a very physical process, and the pace was quite meditative, so I wanted to make a series which just used landscape images in book form to suggest this sense of an internal journey. Over the course of the year, I spent about five months walking every day. In total it was about three and a half, four thousand kilometres. I put that out the following year as a self-published book and an exhibition.

ES: You’ve remarked that in some ways the act of stopping to take a photograph felt like an interruption.

PG: Yeah. That became apparent early on in making the project. At the start I was making a lot more images, stopping more often, trying to find my approach. As I went on I was stopping less often, making fewer images; it became a bit more intuitive, more a reaction to the space rather than trying to conform to some preconceived idea of what an individual work, or the series, should be. I felt a lot of the time that the act of taking the photo would take you out of that sense of connection that you can have with your surroundings.

The Western approach to landscape typically has been very much tied up in thinking from around the Enlightenment era, the sense of distance and separation. In comparison, around the same time, the Eastern approach was more about trying to get across the essence of space, rather than a straight representation of a place, or a particular point of view. I was particularly interested in reading about the way that Chinese landscape painters in ancient times would see themselves as more of a conduit through which the universe expresses itself.

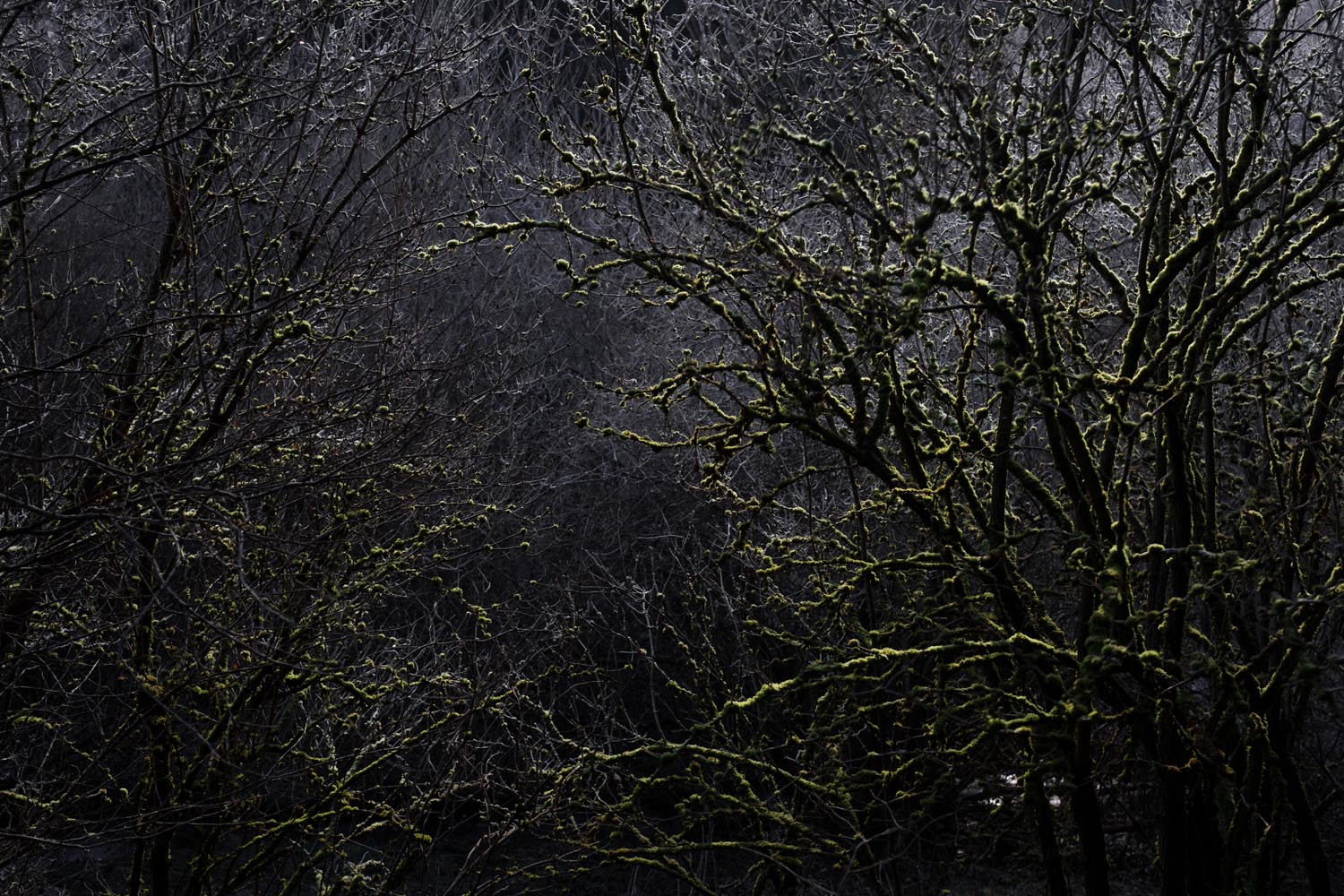

Stray had its beginnings at a two-month residency in Ireland, at a place called Cow House Studios, which is situated on a working farm at the base of a mountain, with a forest right behind. I started making video pieces at night. One night I was coming off this mountain just behind where I was staying, I came through the forest, and I’d misjudged how dark it was getting, and quite quickly got lost in this space. I had this camera which I had set to a very high ISO sensitivity. It was quite a dense pine forest and I had to rely on my limited knowledge of where streams were, and try to orient myself a little bit, but I was really relying more on my sense of touch and hearing. I took some images at the time, and looked at them that evening, and they were super grainy. I left it for a week and when I came back I looked at them again and changed them to black and white, something really started to come up. The camera was picking up much more than my eye could. I felt like I really wanted to explore that further, to be in the space, and allow myself to be immersed, and to rely on my other senses when my vision had been really reduced.

This summer I was talking to a psychologist and academic in Berlin, who explained how the eye works differently under different luminosities. At a certain point, you don’t see colour any more, you just see shade. Little things like that, retrospectively, started to make sense when I was looking at this work. So it was a case of going out there a couple of times a day, just after dusk, and just before dawn. I started to just wander in the forest and trust that I was going to find my way back out. In a similar way to We Make the Path by Walking, I wanted to create a sense of a space through a very loose narrative, to make you feel like you may be moving through the space. But it was not as much about the individual images for me as the previous project, where I had wanted each image to be successful in its own way.

from We Make the Path by Walking @ Paul Gaffney

from We Make the Path by Walking @ Paul Gaffney

Stray install

“I was very conscious of that – of using paths to lead the viewer into the scene in a particular way, or to get across this sense of movement, and other images which try to use it to suggest the heightened sense of awareness of a particular space.”

ES: The language that you were working with in We Make the Path by Walking is very much the language of the document or the topographic image – a description of space that’s wedded to linear perspective. When you’re photographing in full daylight, that Enlightenment paradigm is inescapable – it’s very difficult to avoid making a perspectival image that positions you, and by extension the viewer, in a particular way.

PG: I was very conscious of that – of using paths to lead the viewer into the scene in a particular way, or to get across this sense of movement, and other images which try to use it to suggest the heightened sense of awareness of a particular space. With the new work, I want the process to be less of a cerebral act, and more a case of acting on intelligent instincts. Those intelligent instincts come from a cultural background of anything we’ve ever seen, every conversation we’ve had, all the photographers, paintings or movies we’ve looked at, and how we’ve learned to take photos. As much as possible, I’d like to move towards working in a way that you can have a project in mind but when you’re out there, you try and forget about that. And then when you go back and edit it, it’s a case of trying to translate that experience into something which is meaningful for the viewer. So there’s both sides of the process – there’s a lot of thought going into it, but it’s trying as much as possible to feel like you’re not running away too much in your head when you’re actually in that space where you’re making work, which is a challenge for me. The advantage of We Make the Path by Walking was that I’d been walking for up to a month at a time, that’s all I was doing, and after a week or so I really began to feel very much in that space, or in that mode. I think it’s quite different when you’re in one place and revisiting it, and your day-to-day life is much closer.

For Stray, I could go and walk outdoors and in two minutes I was in the forest. I didn’t start with the idea that I was going to have a completed project at the end of this two month period by any means. It took me the first month just to get into the process, having been doing other things for so long. I set myself a challenge that before I left I was going to make a book, and that’s when the work really started in earnest. There was a printer there, and some basic tools for bookmaking. And the day before I left, I’d made the first dummy of Stray, just full bleed prints folded over and stuck on top of each other with a black card cover. I laid it aside for a few months and then gave some thought as to whether or not to publish it, and I’ve actually gone back to the idea of just making the best prints that I can, and making a handmade book. It’s the first project I’ve done where so much depends on the printing. If the printing’s off, it doesn’t look right.

ES: This is as different as it could possibly be from We Make the Path by Walking, where there’s very much a sense of narrative progress, in the sense of the landscape changing from one image to the next. That work is all about visual descriptions of particular places. Stray is an incredibly tactile object that’s really quite heavy in relation to its size. It’s so dark that it seems to absorb light, and it’s only in a limited sense that it’s about vision – there’s not much information in these images. They’re graphic rather than topographic – the scale of the space, and its location, are quite obscure. Is there meant to be a sense of narrative?

PG: I guess the narrative is not quite as obvious as it was in We Make the Path by Walking, where the individual images were so different from each other and were taken in very different places, so the sense of journey and time passing was more apparent. Whereas with Stray there are no clues given as to the location, or time spent… there’s much more variation in the distance, and it’s perhaps more cinematic. I find that if a series is well sequenced you don’t see the editing, just as they say you shouldn’t notice good design, but if you move things around a little bit out of this sequence, images start to jar, and some of it doesn’t work. It’s not important to me that people see these little decisions, it’s actually preferable that they’re invisible. With both books it was important for me that there would be space for the viewer to read their own stories into the images, and I think a sense of flow certainly helps that. However, it was key that it could somehow convey this sense of being disoriented, at the edge of your comfort zone, though trusting in your senses that you’ll find your way.

The same goes for the design, and the decisions on the size and paper weight were all closely considered. The book looks and feels substantial, and people have been surprised when I’ve told them that there are just 18 images in there (which was cut down from about 27 originally) as the pages are quite thick and have the feel of a children’s fairy tale book. I exhibited Stray at Belfast Exposed in October 2015, and we decided that it would be more of an experimental exhibition where the process would be visible and evolving. Trying out different ideas, figuring out how to show the work in different stages. We chose to use the first three weeks to experiment with different approaches to printing and sequencing, and then to try projections for the second half of the run.

ES: So the installation was a way of working out what the final presentation would be?

PG: Yeah, exactly. I’d had the idea that I wanted to try and project the images as well as using the prints. I had spent a lot of time over the summer experimenting with scale, and printing on different papers. We opened the show with quite a linear sequence, but I felt that it fell somewhat short of being the immersive experience which I had been intending to create.

ES: I sometimes find that a book presentation works better with very dark prints, because it puts you closer to them and provides an additional element of sensory input.

PG: I know what you mean. I wanted to reduce those barriers wherever possible, so we mounted the images directly on the wall, which got around some of the issues you can sometimes have with exhibiting dark prints behind glass. It somehow had the effect of making the images appear less photographic, and some viewers remarked that they looked more like chalk drawings. In hindsight, all of these print experiments, were preparation for finding the best way to produce the book, which is actually printed with the same ink, same printer, same paper, same weight of paper, as the exhibition. The sequence on the wall came from editing for the book. It’s actually how I usually seem to work, I’m thinking about how it will work as a book sequence, then trying to find a way from there to work on the wall.

ES: The experience that you had when you made the images for Stray was one of really losing a sense of distance. When your vision shuts down, when you’re not able to see anything more than lights or tones a few meters ahead of you, everything else ramps up – you hear everything, the ground that’s under your feet starts to become significant, your world becomes much smaller.

PG: In that sense, I think the projections were so much more successful than the prints. The whole space was blacked out. We had eight projectors, each on slightly different timings, so the images were coming on and off independently throughout the space. When you walked in at first, you could barely see anything, it took a minute or so to be able to see the images properly, because they’re so dim. Eventually you got more of a sense of the space, and with the images coming on and off, it encouraged you to move around the room. With regards to creating a sense of being immersed in the space and involving the viewer in a participatory way, it worked quite well. The prints on the wall felt like an interim stage. People liked them, but for me the presentation felt too static, too linear.

ES: The tendency often seems to be that if it doesn’t feel immersive at A3, let’s just make it bigger.

PG: I somehow knew that this wouldn’t be the way to go, though I tried different things. I tried it in different sizes, at different heights, and although I was happy with the way that strategy had worked for We Make the Path by Walking, I knew fairly early on that it was not going to work for this. I considered experimenting with large A1 sized prints, and I scanned A4 sized prints at a very high resolution with the aim of printing from these files as they have a very different look, and appear less noisy. The images are taken at 25000 ISO, hand-held at a very slow shutter speed, so it’s all very shaky, and I had very limited control over the focus. In the end these ‘imperfections’ became an important part of the aesthetic of the book, and also carried across well to the projections.

ES: How conscious were you of actually taking photographs at the time? Or were you more aware of simply being in the space with the camera?

PG: What would happen is that when you get in a space which feels totally black, you end up being drawn to these little pools of light. But then the camera sees a lot more than I do. A lot of the detail that I couldn’t see appears in the print, and even though my vision was restricted, I was still holding the camera up to my eye.

from Perigee @ Paul Gaffney

from Perigee Polaroids @ Paul Gaffney

from Three Days in Tharoul @ Paul Gaffney

“The Western approach to landscape typically has been very much tied up in thinking from around the Enlightenment era, the sense of distance and separation. In comparison, around the same time, the Eastern approach was more about trying to get across the essence of space, rather than a straight representation of a place, or a particular point of view.”

ES: That’s interesting. Is that important?

PG: I think it was, because to a degree I still felt like I was in ‘image-making mode,’ though for the next project I did a couple of weeks later, Three Days in Tharoul, I tried a different approach. Fabrice Wagner, a photographer and publisher from France, who is based in Brussels, has a very interesting project where once or twice a year he invites a photographer, a writer and a bookmaker to come to his friend Philippe’s c18th farmhouse in the middle of nowhere in Belgium and asks you to make a book in three days. You have a day to shoot, a day to edit and print the work, and a day to put the book together. Colin Pantall was the writer, and Pierre Liebaert, a Belgian photographer, made the book itself. Jacky LeCouturier did the printing and Fabrice and Philippe were also very much involved in the process (Philippe even created a stamp to emboss the cover at his forge on the farm).

I felt the pressure of having to produce a series in such a short time, and for most of the day it seemed like I was making B-sides to We Make the Path. At a certain point I decided to just let go and start working more loosely, shooting with the camera held to my chest and keeping direct eye contact with my surroundings. I then found this quite small space just shortly before sunset. The combination of the wet ground, the light, the leaves at that time of year, I thought it was amazing. The images were all made in about 45 minutes at dusk, and about 20 minutes before dawn the next day. Then we had a chance to go back, do a quick edit, and make some colour photocopies, which I used to make a quick dummy. The printing stage was tricky enough because it was all double-sided and we needed to be quite exact – and then on the third day, it was Pierre who put the book together. We had this amazing dinner, and a few people were invited over. It was just this one-off book that stays on the farm. Over time there will be a library of unique books recording different people’s interpretations of this place.

ES: You seem increasingly to be working at the very edges of vision. With We Make the Path by Walking, you already felt that stopping to make the image constituted an interference. The more recent projects are far more focused on being in the space. Stray, for instance, is about an immersive experience where the technology can see more than you can, and you are experiencing and moving through space on a much more basic sensory level.

PG: I was recently speaking to another artist who mainly works at night, and we were discussing how, in a very primitive way, your senses prick up, every little sound is perceived as a potential danger. Even if you’re comfortable in a place, in the winter in the dark, you do feel slightly different. For a recent project I did for the Centre National de l’Audiovisuel in Luxembourg I made images by full moon in the Ardennes forest. It’s called Perigee, which means ‘close to earth’. I also shot Polaroids in the intervening weeks between full moons. It was almost like note-taking, finding routes that I’d later re-visit in the limited time around the full moon rather than finding individual images that I re-shot as such. In the end I quite liked the Polaroids too. I like their ambiguity, and the fact that with both sets of images, you’re not quite sure whether it’s day or night.

ES: They’re quite Pictorialist, the Polaroids.

PG: Yes, they’re quite different to the colour images which I made at night. It’s also a looser way of working and more playful, and there’s more of an element of chance involved. The aesthetic of black and white Polaroids perhaps lends itself to that Pictorialist feeling too.

ES: The Ardennes forest is heavily managed; it’s very groomed in a lot of places.

PG: You’re totally right, and I wasn’t expecting that. And the thing about the Luxembourgish Ardennes as well is you have these steep valleys. So a lot of time I was shooting across these valleys, or down into river beds, where things are less managed. Around Luxembourg, the forests tend to look very similar all over. Trying to find a meditative approach to making work – in some ways I don’t want to impose this preconceived idea of how a project might work; I want to react to what’s in front of me, but it took me a while to figure out how to interact with this particular place. I think once I picked this approach that I enjoyed, I was much more into it. But even though it’s made at night, it felt very different to Stray.

ES: In what sense? Because of the environment?

PG: In some ways I felt less immersed in the Ardennes than the last two projects I showed you. It’s a much more wide-open forest, so if you walk under a full moon you can see quite a lot. Also, because it’s not a very wild place, I’m almost trying to actively create a wilderness in the compositions, and I’ve become very attracted to the reveal of what you haven’t seen in the act of photographing. The process is a bit more technical too, as I use a tripod at night for example, and the environment’s much easier to navigate, and for the first time I’m relying on a particular quality of light, which can be a little frustrating at times.

I’m also much more aware of sounds, as I’m hearing noises that I’ve never heard before, wildlife I’m not familiar with. At one point I had a conversation with someone about wolves slowly moving across that part of Europe. So the next time I was out at night and heard strange noises, I thought for the first time ‘could that be a wolf?’ It’s just this kind of thing where all these little influences come in, and that primal fight or flight thing I mentioned earlier is going on, a natural heightening of the senses. So it’s interesting how these little things that happen play a part in how you feel when you’re out in that space.

ES: Do you think you’ll ever work in daylight again?

PG: I’d say so. At the moment I still feel this draw to work at night, it somehow seems that I’m just getting started with it, so I guess we’ll see where it takes me.

Dr Eugenie Shinkle is a Reader in Photography at the University of Westminster

(All rights reserved. Text @ Eugenie Shinkle. Images @ Paul Gaffney.)