“I will argue that the interviews with Francis Bacon are carefully constructed and not very reliable as a form of oral history. However, they are very interesting material from the point of view of the representation of the artist and his strong influence on the interpretation of his work.”

By Sandra Kisters, Nr. 1, 2012 (9 Seiten)

The first time that I saw British painter Francis Bacon (1909-1992) talking about his art, was when I was a student at the academy of arts in Arnhem (The Netherlands) in the 1990s. The documentary the teacher showed us was probably The Brutality of Fact by Michael Blackwood (1984). As an aspiring artist, I was deeply impressed by the ease and persuasiveness with which Bacon spoke about his unsettling paintings. Years later, when I had started to work on a PhD project about controlling the representation of modern artists at VU University in Amsterdam, I selected Bacon as a case study, in particular because he was interviewed repeatedly.

Bacon, who was notorious for his often as ‘violent’ characterised paintings of screaming popes and distorted bodies, as well as for his extravagant life style, was also known for the eloquence with which he talked about his art. He was easy to talk to, and was interviewed countless times by numerous critics. However, when studying Bacon’s paintings one soon comes across the published interviews with art historian, critic and curator David Sylvester (1924-2001). In fact, it was Sylvester who interviewed Bacon in the documentary that I had seen in the 1990s.

When he first interviewed Bacon in 1962, Sylvester was interviewing several contemporary artists, such as Willem de Kooning and Robert Motherwell. But as he kept interviewing Bacon he interviewed him as many as 18 times between 1962 and 1986 – the interviews received a status apart within his career as a critic, and Sylvester became interconnected with the painter. He was not able to really take his distance until after Bacon had died in 1992, or so he wrote in the book Looking Back at Francis Bacon (2000).1

In this paper I will argue that the interviews with Francis Bacon are carefully constructed and not very reliable as a form of oral history. However, they are very interesting material from the point of view of the representation of the artist and his strong influence on the interpretation of his work. In order to illustrate this, I will discuss several themes that reoccur within the interviews, such as the mythological beginning of his career as a painter with the triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), his working methods and the role of his studio. Further- more, I will discuss the interviews as a marketing tool, and Sylvester’s own reflection on the interviews, which he discussed with art historian Andrew Brighton at the London Tate in 2000. In the last few decades, artists’ interviews have become an important source and tool in art historical discourse and research, but their usefulness and reliability can differ significantly, as can be demonstrated with the Bacon interviews.

The Interviews

Sylvester’s first interview with Bacon was recorded in October 1962 and broadcasted on BBC radio on March 23, 1963.2 Although they had known each other since the 1950s, and Sylvester already had written about his work, the idea for the interview was not Sylvester’s.3 Instead, BBC radio had asked him to interview him following Bacon’s successful one-man show at the Tate Gallery in 1962. In the previous years, Sylvester had kept his distance towards Bacon because he found Bacon’s critical response to Jackson Pollock’s paintings childish and he did not like the paintings that Bacon himself was producing around 1957-1958.4

The first interview was structured around the term accident – one of Bacon’s favourite terms. With accident Bacon meant that he might have had a general idea about what he was going to paint, but that through the process of painting he came to different in- sights and solutions.5 In the interview Bacon and Sylvester discuss several themes that would reoccur in all Bacon interviews: next to the elements of accident and chance Bacon refers to his image depository– when Sylvester asks him about the influence of a Cimabue crucifixion (1272-4) – and says that: “Yes, they breed images for me. And of course one’s always hoping of renewing them.”6 But they also discuss his tendency to destroy his paintings, even the better ones, his lack of using preliminary sketches or drawings, and his wish to avoid story telling, or a narrative interpretation of his paintings. Lastly, they discuss Velázquez and the influence of photography on his work. Although the interviews were held over the course of more than twenty years, their tone and contents are very consistent and one hardly notices the passage of time.

The published interviews are often related to radio broadcasts or documentaries. For instance, the second interview is a compilation of material derived from three days of shooting for the BBC documentary Francis Bacon: Fragments of a Portrait by Michael Gill in 1966. The fifth interview was partially based on recordings for Weekend Television in 1975 and the eighth interview is correlated to the documentary The Brutality of Fact by Michael Blackwood that was mentioned earlier.

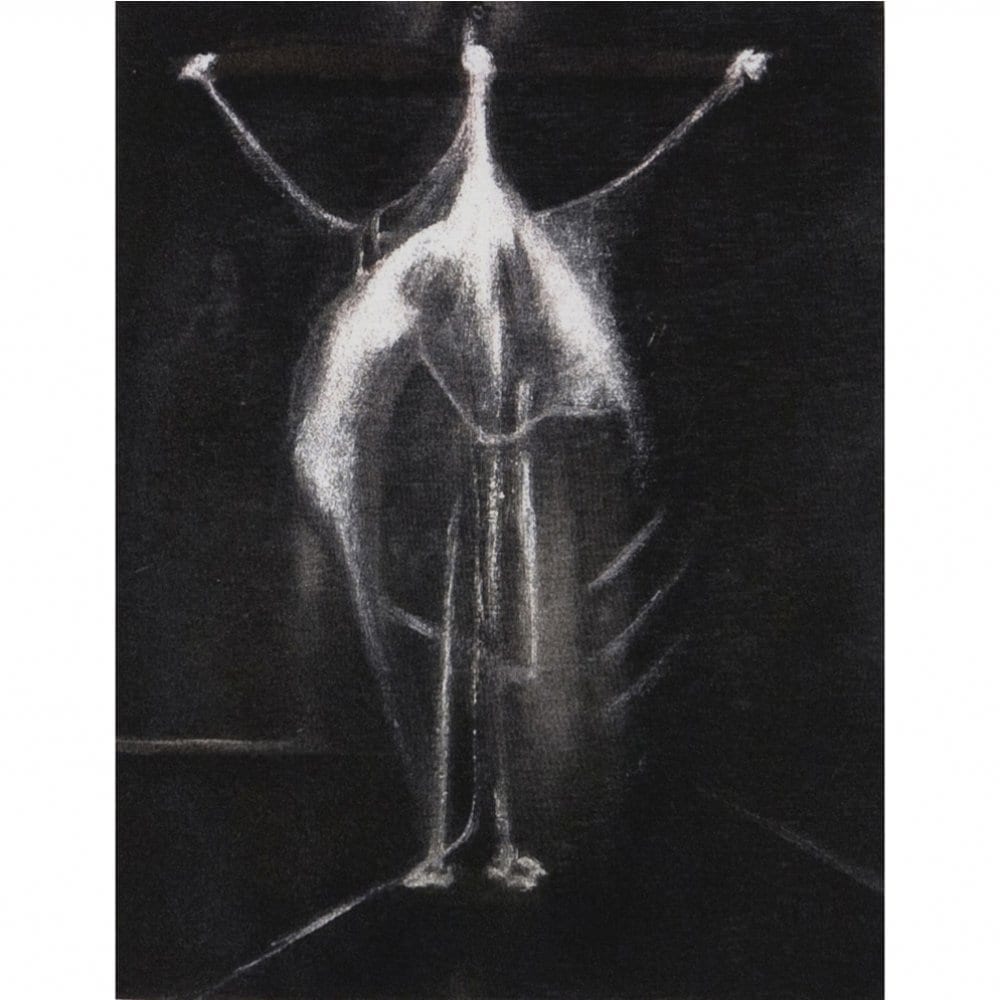

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944

Subsequently, Bacon always claimed that he did not paint between 1937-1944, but it is more likely that he did paint, but was not satisfied with the results and destroyed the paintings, as was his habit; being a severe critic of his own work.

The First Work

It is no coincidence that the first interview, both in the edited edition as in the radio broadcast, starts with a discussion of Three Studies of Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), the triptych that Bacon regarded as his first autonomous work of art.7 Bacon always claimed that his career as a painter began with this triptych. The only earlier work that he acknowledged was Crucifixion (1933). Bacon, who had initially worked as an interior designer and designer of modernist furniture and carpets, started painting seriously around 1933, although some paintings from the 1920s have survived.8 These early works were heavily influenced by artists like Pablo Picasso, Graham Sutherland and Roy de Maistre, something Bacon did not like to acknowledge, except for the influence of Picasso.9

To interviewers he always downplayed this period as a time in which he was drifting and drinking; but not working seriously as an artist. In the third interview Sylvester asks Bacon why he was such a late starter. He suggests that Bacon did exceptional work, both as a designer, and as a painter in the early 1930s, but that he did not do a lot of painting in the following years. Bacon answers: “No. I didn’t. I enjoyed myself.”10 Bacon also states that he did not consider painting as a serious profession until much later. But if this were right, why then would he consider participating in the group shows at the Mayor Gallery in 1933 and Agnew’s Gallery in 1937, both in London? He even organised a solo exhibition of his own work in the so-called Transition Gallery in 1934. As one of Bacon’s biographers, Michael Peppiatt, argued, Bacon was so disappointed about the harsh critiques that he received of his works at these exhibitions, that he destroyed all the unsold works.11

Subsequently, Bacon always claimed that he did not paint between 1937-1944, but it is more likely that he did paint, but was not satisfied with the results and destroyed the paintings, as was his habit; being a severe critic of his own work.12 Only when he was confident enough about his new work, supported by artist Graham Sutherland and his new lover Eric Hall, did he exhibit again; in a group show at the Lefevre Gallery in London in 1944, where his work was noticed by several art dealers and collectors such as Erica Brausen of Redfern Gallery (she later owned the influential Hanover Gallery) and Colin Anderson.13

From then on, Bacon kept pointing to Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion as the starting point of his career as an autonomous artist, and increasingly managed to influence both publications and exhibition displays into showing no works previous to the triptych.14 By focusing on the triptych as the start of his career, he presented himself as a radical post-war painter, and not as an artist who had been struggling to find his own style.15 By starting the edited interviews with Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Sylvester supported Bacon’s claim.

Studio Practice

Although Bacon loved to show his studio to interviewers and photographers – for instance, he seems to really enjoy Melvin Bragg’s shocked reaction to the absolute chaos in his studio when he shows it to him in the episode of The South Bank Show in 1985 – he was never very open about his studio practice. The information he gave, was the information he wanted to give, and no more. For example, Bacon openly talked about the influence of the photographs of Eadweard Muybridge and a book by K.C. Clark about Positioning in Radiography (1939); he discussed them with Sylvester in the second interview (1966), but he did not explain how exactly he used them. In the same interview they discuss the influence of Velázquez, whom he greatly admired, but supposedly only in reproduction, and the film The Battleship Potemkin (1925) by Sergei Eisenstein.

In the documentary by Michael Gill, whereupon this interview is based, we see Bacon and Sylvester on their knees in the studio, picking up re- productions, books, photographs (Bacon had his friend John Deakin make photographs of some of his friends in the 1960s), all crumpled and covered with paint. Bacon says:

“Well, my photographs are very damaged by people walking over them and crumpling them and everything else, and this does add other implications to an image of Rembrandt’s for instance, which are not Rembrandt’s.”16

He implies that others damage the materials and that he passively lets it happen; that it is not an active working method. However, since the relocation of the studio, a lot of research has been done into the way in which he used these sources, and in particular Bacon scholar Martin Harrison has made some remarkable discoveries.17 Harrison pointed out that Bacon folded his source material, using paper clips to hold a certain fold, thus creating distorted images of the human body.

Although Bacon kept emphasising the element of accident and chance in the interviews with Sylvester, scholars such as Harrison have demonstrated that this is only partially true. The stains and smudges on the photographs and reproductions are accidentally, but the way he used them was not. Also, the tidying of the studio – by sometimes throwing away materials and destroyed paintings – and the organisation of the materials throughout the studio turned out to be more systematic than Bacon led on to believe.18

Bacon always was very persistent in denying the making of preliminary sketches. Although he said to Sylvester in the first interview that:

“I often think I should, but I don’t. It’s not very helpful in my kind of painting. As the actual texture, colour, the whole way the paint moves, are so accidental, any sketches that I did before could only give a kind a skeleton, possibly, on the way the thing might happen.”19

He kept stating that he did not draw, although he said in the last interview (1984-1986): “Well, I sketch out very roughly on the canvas with a brush, just a vague outline of something, and then I go to work, generally using very large brushes, and I start painting immediately and then gradually it builds up.”20 The last unfinished painting that was found on the easel in his studio confirms this remark. Posthumously however, several collections of drawings surfaced, of which some have been studied by experts who have confirmed their authenticity.21

The studio itself is not discussed in the interviews until the last edited interview of 1984-1986. This interview is for a large part based on the recordings for the documentary by Michael Blackwood of 1984. It contains the most biographical information about his youth and artistic development, although Bacon again stresses: “And it was then, about 1943-44, that I really started to paint.”22 The period 1929-1943 is skipped altogether. It is the first time that his studios are being discussed, the different locations, the circumstances that Bacon needs to be able to work and the reason why they tend to become so very messy within days. Bacon says that he needs the (created) chaos because it breeds images for him. In the documentary his friend John Edwards jokes that Bacon loves a chaotic atmosphere as long as the dishes are clean, but this is left out in the published interview. Sylvester suggests:

“It’s probably easier to work in a space that’s chaotic. If painting or writing is an attempt to bring order to the chaos of life, and the room you’re working in is disordered, I think it may act unconsciously as a spur to create order. Whereas, if you try to do it in a very tidy room, there seems to be much less point in getting started.”23

Bacon ‘absolutely agrees’ with him, and goes on to describe how he bought a studio around the corner in Roland Gardens. He decorated the place beautifully, but made it ‘to grand’ to work in. He could not work without the chaos.24 Another apartment that Bacon bought with a studio overlooking the Thames was not used and later sold, because the reflection of the light on the water bothered Bacon, who had covered several windows in his studio at Reece Mews and liked working with the only light coming from a skylight. This interview is rather telling for the importance artists give to the atmosphere of the places where they are working, and how afraid or even superstitious they are of leaving a successful formula.

Crucifixion, 1933

Marlborough Fine Art had a reputation for presenting their artists’ works in a museum-like display, and publishing accompanying catalogues modeled after the catalogues of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.25 They also lobbied intensively to realise solo exhibitions of their artists in renowned museums.

Using Interviews as a Marketing Tool

Bacon’s first dealer was Erica Brausen of the Hanover Gallery in London. In 1958 he unexpectedly changed to the Marlborough Fine Art Gallery, a more commer- cial gallery that already represented artists such as Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Graham Sutherland. Marlborough Fine Art had a reputation for presenting their artists’ works in a museum-like display, and publishing accompanying catalogues modeled after the catalogues of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.25 They also lobbied intensively to realise solo exhibitions of their artists in renowned museums.

From 1960 onwards, Marlborough Fine Art started to promote Bacon more openly and commercially than Brausen had done. Catalogues contained more biographical information than before and, next to reproductions of his work and lists of museums that had works by Bacon in their collections; photographs of the painter himself were used. The first catalogue for Marlborough Fine Art, Francis Bacon: Paintings 1959-1960, contains a photograph that Cecil Beaton took of Bacon in his Battersea studio. The series Beaton took also contains photographs in which the messiness of the studio is visible. The one that was in- cluded in the catalogue shows Bacon who confidently looks into the camera and is positioned between several of his paintings that are for sale in the exhibition. In the following years Bacon the man and his studio became more present in catalogues that were meant to promote his work. In fact, combining private photos such as pictures of Bacon drinking and laughing on the Orient Express, made by John Deakin, combined with valuable paintings – intimacy and exclusiveness – seems to be an inventive marketing strategy.26

The Marlborough catalogues, nearly always, included texts by eminent writers such as Robert Melville, John Russell or Michel Leiris. Unsurprisingly, the gallery was quick to recognize the value of the interviews with Sylvester. Extracts of the first interview for BBC radio were included in their exhibition catalogue Francis Bacon: Recent Work (1963) and the second Bacon interview by Sylvester was published for the first time in the exhibition catalogue Francis Bacon: Recent Paintings (1967).27 This catalogue also includes film stills from Gill’s documentary in which Sylvester interviews Bacon. The inclusion of Bacon interviews in catalogues of Marlborough Fine Art or Galerie Maeght Lelong (Paris) continued up until the ninth interview, which was published in Francis Bacon: Paintings of the Eighties (1987) as ‘An unpublished interview by David Sylvester’.

Francis Bacon @ Cecil Beaton

Editing the Interviews

David Sylvester interviewed Francis Bacon as many as 18 times between 1962 and 1984-1986. The first four interviews were first published in 1975 as Interviews with Francis Bacon, followed by expanded editions in 1980 and 1987. These expanded editions of the interviews contained first seven and than nine interviews in total, so the material of the 18 interviews has eventually been condensed into nine texts. It is common knowledge that Sylvester edited the interviews, and he mentions it himself in the introduction the first edition of Interviews with Francis Bacon (1975).28 to Bacon and on which Bacon filled in some of the answers.37

One of the questions is about his decision to stop being a designer to become a painter. Bacon wrote on the questionnaire that he was never any good as a designer and became more interested in painting. Than Sylvester included the question:

Sylvester: “Why do you feel it useless to use drawings or oil-sketches?”

Bacon [hand-written]: “Directness of statement” [and crossed out] “fact emphasising not xxxxx”

Typed: “The brutality of fact”.38

In the preface of the first edition, Sylvester admits that the texts have been heavily edited, although he uses “Bacon’s turn of phrase”.29 Only a fifth of the material in the transcripts has been used in the edited collections. With the exception of the first interview, most of the other interviews are compilations of two or more interview sessions. “In order to prevent the montage from looking like a montage, many of the questions have been recast or simply fabricated”, Sylvester wrote.30 Sylvester used four types of ‘spoken material’ as sources for the written interviews: interviews for the radio of other forms of distributions recorded on tape, filmed interviews, private tapes made by Sylvester himself and notes he took while talking to Bacon, which Sylvester refers to as ‘unrecorded conversation’.31 He included the so-called leftover material in Looking Back at Francis Bacon (2000).32

Less known is the fact that Bacon himself was involved in the editing process.33 In a book review of the first edition of the interviews in 1975, Stephen Spender assumed that: “he has given an exact transition of Bacon’s words, with only ‘minimal modifications to clarify syntax’.”34 In 2000 however, Sylvester himself wrote that Bacon sometimes would call him at about eight in the morning to discuss a certain phrase or thought with him. “Such turns of phrase didn’t always come on the spur of the moment.”35 Even more tellingly, at the time of its relocation from London to Dublin, manuscripts of the eighth interview (1982-1984) where found in Bacon’s studio, edited by Bacon himself.36 In addition, the Francis Bacon studio database also contains a questionnaire that Sylvester sent.

The manuscripts are rough transcripts of the interviews, and they show how Bacon and Sylvester carefully were searching for the right phrases. Although it is understandable that Sylvester edited these passages in order to condense them into coherent paragraphs, the literal transcriptions show how the conversation actually takes place.

Sylvester: “But you say there is a subjective and an objective realism.”

Bacon: “No, I don’t say ….” Sylvester: “Sorry.”

Bacon: “…. I don’t think there are two different realisms.”

Sylvester: “Ah, right. Sorry.” Bacon: “I think realism incorporates the subjective and the objective.”

Sylvester: “Yes.”

Bacon: “No, I don’t for a moment think there are two realities.”39

The end result of the written interviews gives the impression of two amiably talking art professionals, who both appear to be very eloquent and articulate. This is a great accomplishment of Sylvester (and co- editor Shena Mckay) and not unimportant for his own image of an insightful art critic.

It is interesting though, that Bacon apparently got to see several draft versions of the eighth interview before it was published and got a chance to comment on it. The corrections in the manuscript seem to focus in particular on how Bacon wants his work to be described, such as his vision on realism, which in the published interview is connected to the work of Picasso and Van Gogh. 40

In addition, it is obvious that Bacon felt very strongly about phraseology. He erased words like ‘very, very’, or ‘well’, and ‘you see’, but added words like ‘accident’ and ‘artificial’.41 Bacon was controlling biographical information in the sense that he avoided answers to questions – like in the questionnaire – about his training as an artists or the shift from interior design to painting. However, this manuscript does not contain a lot of biographical data. The most biographical interview is the last (ninth) interview. Part of the answers to the questionnaire however, return in this last interview.

David Sylvester’s personal archive probably contains tape recordings of numerous artists’ interviews, including the ones with Bacon and other manuscripts of the Bacon interviews. The archive was purchased by the Tate Archive from Sylvester’s Estate in 2008, and is located in the Hyman Kreitman research Centre at Tate Britain.42 Once these papers become catalogued and available for researchers, research into this matter can be conducted and may provide further interesting insights into their collaboration and Sylvester’s approach to interviews with other artists.

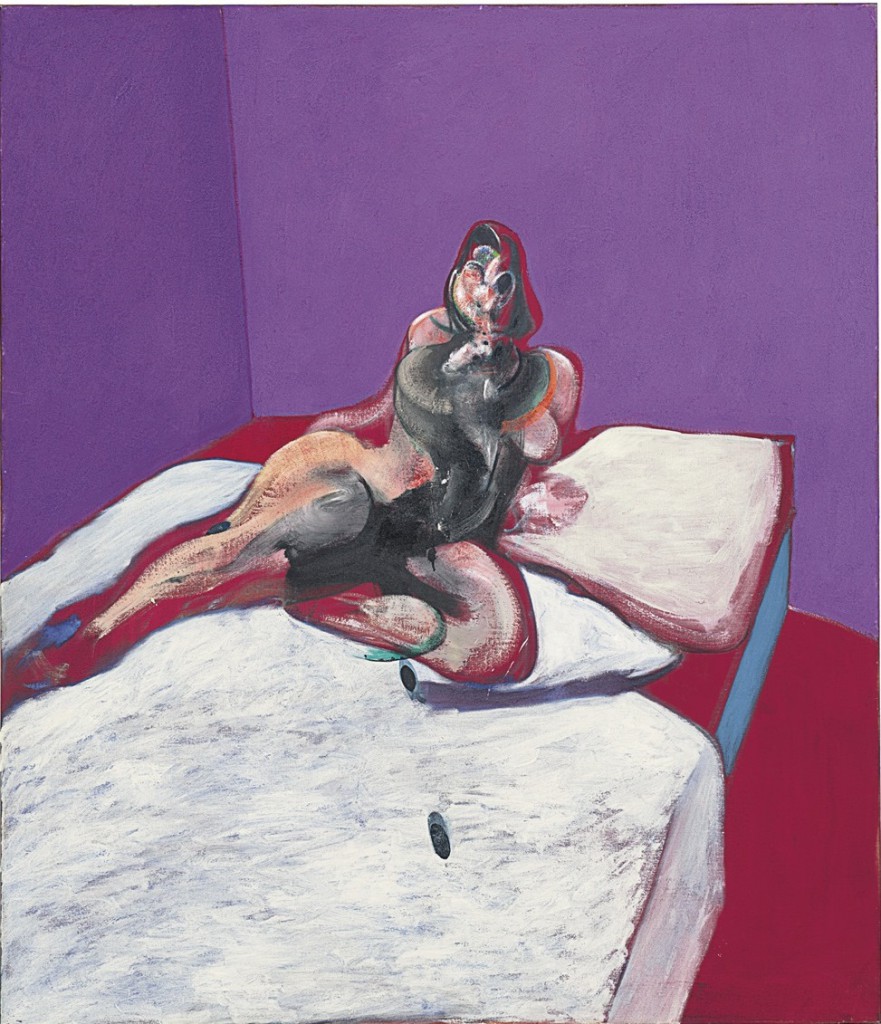

Portrait of Henrietta Moraes, 1963

He felt that for artists it is essential not to expose everything to the public. Nonetheless, the drawings, over-painted photographs, and the hand-written notes, are of great importance.

Interviewing David Sylvester

In 2000, Andrew Brighton, an art historian and at the time senior curator of public programmes at Tate Gallery, held a public conversation with Sylvester to celebrate the publication of his book Looking back at Francis Bacon (2000).43 Sylvester had just gotten out of the hospital, and was still very fragile – he would die a year after –, but he was very candid and willing to talk about the process of interviewing Bacon. Brighton was curious to know whether he felt that Bacon had learned how to formulate his ideas about art through Sylvester, but he denied this forcefully. Looking back, he regarded the first interview with Bacon as the best one. Bacon’s personal language was already there. According to Sylvester one could argue that Bacon did not really develop his ideas after the first two inter- views, since he kept on drawing from them. One should also note, that in 1962, at the time of the first interview, Bacon already was in his early fifties and had formulated a strong vision about his own art.

At the time of the first publication of the collected Interviews in 1975 Sylvester had been criticized for not being objective. Willem Feaver mentions in The Listener that Sylvester: “becomes the impresario and director, controlling the flow pattern, presenting his star at his best.”44 It took Sylvester five exhibitions and a book to leave Bacon behind. These exhibitions would not have been possible while Bacon was alive, Sylvester told Brighton, since Bacon would have definitely interfered.45 For the same reason he felt the need to write Looking back at Francis Bacon:

“It seemed to me that, while the interviews were in progress and I was serving as a sort of henchman to the artist, I couldn’t trust myself to perform with detachment as a critic or historian of his work. Shortly after he died, the floodgates opened and this book is the consequence.”46

Brighton started the public discussion by asking if Sylvester ever felt that Bacon was misleading him, for instance regarding the existence of preliminary sketches. Sylvester answered that he did see drawings on the last page of a paperback edition of poems by T.S. Eliot, but that he regrettably did not confront Bacon about it.47 “I had been gullible enough to not have realised that these were the tip of an iceberg.’48 However, Sylvester did not regard this as a deliberate conceit. He felt that for artists it is essential not to expose everything to the public. Nonetheless, the drawings, over-painted photographs, and the hand-written notes, are of great importance. They give insight into the process of transformation that Bacon applied: [on] “how he could superimpose the images”, as Sylvester put it.49

Today, these sources are an important focus of new research on Bacon, and one could say that they lead attention away from the work itself; something Bacon was very keen on preventing. As Sylvester pointed out, he was a modernist art historian, mainly interested in formalistic aspects and therefore did not pay a lot of attention to a psychoanalytical approach to Bacon’s work or the identification of all of Bacon’s source materials. Brighton on the other hand was interested in autobiographical elements, in particular regarding Bacon’s youth, in his paintings and discussed these later on in the publication Francis Bacon (2001).

In the public interview Brighton confronted Sylvester with the question that he had been a part of Bacon’s construction and manipulation of his own reception. Sylvester was very frank in his response and admitted that the more he learned about Bacon, the more he became aware that he was very influenced by his image.

In the public interview Brighton confronted Sylvester with the question that he had been a part of Bacon’s construction and manipulation of his own reception.50 Sylvester was very frank in his response and admitted that the more he learned about Bacon, the more he became aware that he was very influenced by his image. But, as Sylvester rightfully argued: in order to interview an artist, one has to go along with his vision to a certain degree, or the interview will not go very smoothly or even come to an end. Sylvester continued to say that as an interviewer, one should not interfere too much. One should let the artist talk, like a psychoanalyst let’s his patient talk. He said that if he would have mentioned for instance that he saw influences of Rothko in Bacon’s paintings, while Bacon denied such interpretations, the interview would have stopped. At the end of the interview Brighton asked Sylvester how he had gotten Bacon’s trust, upon which Sylvester answered that he did now know if he ever had it.

Conclusion

The influence of Sylvester’s published interviews with Francis Bacon is still significant. Almost every text about Bacon contains quotations from them. Bacon used the interviews to formulate and refine standard answers to recurring questions from the press, such as an explanation for the ‘horrific’ character of his work, the motif of the crucifixion, or the placement of his paintings behind glass. His explanation for the use of the crucifixion theme in the second interview from 1966 is well-known: “Perhaps it is only because so many people have worked on this particular theme that it has created this armature – I can think of no better way of saying it – on which one can operate all types of feeling.”51 Another famous remark is about the connection that according to Bacon exists between meat and the crucifixion: “Well, of course, we are meat, we are potential carcasses. If I go in a butcher’s shop I always think it’s surprising that I wasn’t there instead of the animal.”52 Questions about the use of religious iconography, autobiographical interpretations or the narrative aspects in his work were cleverly evaded.53 Bacon only hinted at his working methods, such as the use of dust or the throwing of paint. He discouraged a thorough analysis of his work and always referred to the same inspirational sources: Picasso, Velázquez or Van Gogh, photographers like Muybridge or books on radiology and diseases of the mouth, and films by Eisenstein.

In recent years, artists’ interviews have become an important source for museums for the documentation of the way in which art works are to be installed and preserved, but they also continue to be an important source for historical research.54 As I have argued, Sylvester’s interviews with Francis Bacon are carefully constructed and therefore not very reliable as a form of oral history, but they are extremely interesting from the point of view of representation and of the controlling of the interpretation of the work.

As Sylvester rightfully mentions, the interviewer has a difficult position. In hindsight it is easy to criticise the interviewer for not being critical enough or for missing certain things, such as the existence of hand-written notes and sketches by Bacon. Moreover, he can be accused, as Sylvester was, for being used as a henchman. But in order to gain an artist’s trust and to be able to talk in depth about his art, one perhaps has to except that certain topics are difficult to address.

Endnotes

1. David Sylvester, Looking back at Francis Bacon, London 2000, p.8.

2. David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon, (1987) New York 2004, ‘Editorial Note’, p. 202-203. The original interview can be listened to on the BBC archive website – Francis Bacon at the BBC – http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/bacon/5412.shtml.

3. Sylvester 2000, Looking back at Francis Bacon, p. 8. They met in 1950.

4. ‘David Sylvester on Francis Bacon in conversation with Andrew Brighton’, Tate Modern June 6, 2000, TAV 2217 A. Tate Audiovisual Archive, Hyman Kreitman Research Centre, Tate Gallery, London, hereafter referred to as TAV.

5. A similar analysis of the painting process, not as a static form of intention, but as a “numberless sequence of developing moments of intention”, is given by Michael Baxandall in Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures, (1985), New Haven and London 1986, p. 63.

6. Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, p. 14.

7. See for a discussion of the Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion as ‘primary work’, Sandra Kisters, ‘Orchestrating the beginning – Francis Bacon’, in Véronique Meyer and Vincent Cotro [eds.], Le Première Oeuvre, Universities of Tours and Poitiers, forthcoming 2013.

For image see: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/ba- con-three-studies-for-figures-at-the-base-of-a-crucifixion-n06171

8. See Martin Harrison, In Camera: Francis Bacon, Photography, Film and the Practice of Painting, New York 2005, p. 38. Harrison refers to Roy de Maistre, Bacon’s mentor and lover in the 1930s, who painted Bacon’s studio at Royal Hospital Road in 1934. In the painting Bacon’s studio is clearly filled with semi-abstract paintings.

9. As Martin Hammer, Andrew Brighton, Anne Baldassari and Martin Harrison already have shown, Bacon was influenced by Roy de Maistre, Pablo Picasso and Graham Sutherland, amongst others. See Martin Hammer, Bacon and Sutherland, New Haven and London 2005, Andrew Brighton, Francis Bacon, London 2001, Anne Baldassari, Bacon-Picasso: The Life of Images, Paris 2005, Martin Harrison, In Camera: Francis Bacon, Photography, Film and the Practice of Painting, New York 2005.

10. Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, p. 70.

11. Michael Peppiatt, Francis Bacon: The Anatomy of an Enigma, New York 1996, p. 67-68.

12. He for instance told this to John Rothenstein, the director of Tate Gallery at the time of Bacon’s first retrospective exhibition at the Tate. See John Rothenstein ‘Introduction’, in John Rothenstein and Ronald Alley (eds.), Francis Bacon, London 1962, exh. cat. Tate Gallery.

13. The importance of the friendship with Graham Sutherland for the development of his career as a painter has been described thoroughly by Martin Hammer, Bacon and Sutherland, New Haven and London 2005. See for instance, p. 14 and 30.

14. In the catalogue of the 1962 retrospective at Tate Gallery, four works from before 1944 were included, while in later catalogues, such as the catalogues for retrospectives in respectively 1971 Grand Palais in Paris and 1985 at the Tate all start with the Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion as the first (colour) plate. A more detailed discussion of the growing influence of Bacon on his retrospective exhibitions at Tate Gallery in 1962, 1985 and even the posthumous exhibition in 2009 can be found in Kisters, ‘Orchestrating the beginning – Francis Bacon’, in Meyer and Cotro (eds.), Le premiere Oeuvre (forthcoming 2013).

15. Op. cit 9.

16. Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, p. 38.

17. See Harrison 2005, In Camera, Barbara Dawson and Martin Harrison [eds.], Martin Harrison, Francis Bacon: Incunabula London 2008 and Francis Bacon: A Terrible Beauty, exh. cat. Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane, Dublin 2009.

18. See the analysis of Bacon’s studio contents in Margarita Cappock, Francis Bacon’s Studio, London 2005.

19. Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, p. 21.

20. Ibid., p. 194-195.

21. Matthew Gale researched and described the collections of poet Stephen Spender and Bacons friends Peter Pollock and Paul Danquah in Francis Bacon: Working on Paper, London 1999. Other collections, such as Barry Joule’s, are still the topic of debate.

For image see: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/bacon-fig- ure-bending-forwards-t07358

22. Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, p. 189.

23. Ibid, p. 191.

24. Ibid, p. 189,

25. Brighton 2001, Francis Bacon, p. 75

26. See for instance the catalogue Francis Bacon. Recent Paintings, London 1965.

27. The Marlborough Fine Art Gallery did all kinds of other promotional activities, such as initiating retrospective exhibitions, like the one in Tate Gallery in 1962. This is discussed in my dissertation Leven als een kunstenaar. Invloeden op de beeldvorming van beeldend kunstenaars. Auguste Rodin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Francis Bacon, VU University Amsterdam 2010, p. 321-326.

28. He edited the interviews together with Shena Mackay, see Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, p. 203. In an ‘Editorial Note’ at the end of the edition of 2004 he gives additional information about the sources for each edited interview.

29. Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, p 6-7.

30. Ibid.

31. Ibid, p. 7.

32. Sylvester 2000, Looking back at Francis Bacon, p. 8. In part 3 ‘Fragments of Talk’ Sylvester included leftover material of the 18 recordings, which is grouped in themes.

33. I would like to thank Margarita Cappock, Head of Collection at Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane, for bringing the manuscripts of the interviews that were found in the studio to my attention.

34. Stephen Spender, ‘Armature and alchemy’, Times Literary Supplement, March 21, 1975, p. 290-291.

35. Sylvester 2000, Looking Back at Francis Bacon, p. 191.

36. They were found during the relocation of the studio from London to the Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane, and can be consulted through the database of the Francis Bacon Studio Project, Dublin under the numbers F1A:122A, F1A:122F, F1A:122G, F1A:122J, F1A:122K and F1A:122M. 36. I would like to thank the Francis Bacon Estate for their permission to include a few quotations from these manuscripts.

37. Francis Bacon Studio Project, F1A: 122A. The answers are partly typed, partly handwritten and partly crossed out.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid. p. 5.

40. Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, in particular p.170-71.

41. Francis Bacon Studio Project, F1A: 122G. Typed manuscript of an edited interview of Sylvester with Bacon entitled ON REALISM: Interview with Francis Bacon by David Sylvester recorded in 1982, 15 pag.

42. ‘The personal and professional papers of the curator, writer and art historian, David Sylvester, 1940s–2001’, purchased from the Sylvester’s Estate, 2008. Tate Gallery Archive, Hyman Kreitman Research Centre, Tate Gallery, TGA 200816. The Sylvester papers are currently uncatalogued and are therefore difficult to consult.

43. TAV 2217 A.

44. William Feaver, ‘All flesh is meat’, The Listener, May 15 1975, p.

652-653.

45. TAV 2217 A.

46. Sylvester 2000, Looking back at Francis Bacon, p. 8.

47. The Francis Bacon Studio Project has a large amount of books covered with drawings or paintings in their archive: see http://www.hughlane.ie/history-of-studio-relocation and Cappock 2005, Francis Bacon’s Studio.

48. Sylvester in Matthew Gale, Francis Bacon: Working on Paper, London 1999, p. 9.

49. TAV 2217 A. This superimposing of images; the combination of several inspirational sources within one work has been analysed in depth by Martin Harrison. Op. cit. 17.

50. TAV 2217 A.

51. Sylvester 2004, Interviews with Francis Bacon, Interview 2, p.

30-67, p. 44.

52. Ibid, p. 46.

53. Recently, a new study has appeared discussing this very theme: Rina Arya, Francis Bacon: Painting in a Godless World, London 2012.

54. For instance, the ‘Artist Interview Project’ of the International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art. See: http://www.incca.org/projects/64-current-projects/980-artist-interview-project-incca-na (June 30, 2012).

EXPLORE ALL FRANCIS BACON ON ASX

Sandra Kisters is assistant professor in modern art at Utrecht University, The Netherlands. She defended her unpublished thesis Leven als een kunstenaar (Living the life of an artist. Influences on the image making of modern artists. Auguste Rodin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Francis Bacon) at the VU University Amsterdam in 2010. Recent publications include: R. Esner, S. Kisters and A.-S. Lehmann (eds.), Hiding Making – Showing Cre- ation. The Studio from Turner to Tacita Dean, Amsterdam University Press (forthcoming 2013),’Francis Bacon. Orchestrating the beginning’, in V. Meyer and V. Cotro (eds.), Le premiere oeuvre, (forthcoming 2013), ‘Georgia O’Keeffe’s Häuser in New Mexico: Das Haus als Image-In- strument’, in G.A. Mina and S. Wuhrmann (eds.), Casa d’ Artisti, Museo Vincenzo Vela, Ligornetto 2011, pp. 283-299, and ‘Musée Rodin: Thorvald- sen as a role model’, in Van Gogh Studies III, Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam 2010, pp. 112-133.

(All rights reserved. Text @ Sandra Kisters. Images @ the Estate of Francis Bacon.)