Silver Grill Cafe, 1975

‘When I grew up here, Vancouver was a working port town, and all the streets downtown ended at the harbour. That working port was very much a part of the feel of the city…’ – Greg Girard

For almost 30 years, Canadian photographer Greg Girard has lived and worked in cities across Asia, witnessing the rapid transformation of a region that has changed almost beyond recognition within the span of a few decades.

Born and raised in a suburb of Vancouver, Girard began taking photographs as a high school student in the 1970s, spending days and nights in the downtown districts surrounding the port. In 1974, Girard first travelled to Hong Kong, where he later settled and found work first as a sound recordist for the BBC, and then as a freelance photographer. From 1987 until around 2005, Girard produced editorial work for publications such as Time, Newsweek, Fortune, Forbes, Elle, Paris-Match, Stern, and New York Times Magazine.

Girard’s first book, City of Darkness – an exploration of Kowloon Walled City, produced in collaboration with architectural photographer Ian Lambot – was published in 1993. Around 2000, Girard made a conscious shift away from commercial work, and began taking photographs ‘unburdened by the consideration of whether a magazine might be interested in the pictures or not.’ Since then, he has published four books ¬– Phantom Shanghai (2007), Hanoi Calling (2010), In the Near Distance (2010), and City of Darkness Revisited (2014). Girard continues to keep a foot in both worlds, producing editorial assignments for magazines like National Geographic alongside his personal projects. Kominek Books will soon be releasing a second volume of his previously unpublished early work.

Much of Girard’s work reflects on the social and physical transformation of Asia’s urban centers since the 1990s: ‘pictures that show what modernity looks like, especially in cities.’ His photographs also give a remarkably vivid sense of the way that globalisation itself – the complex processes and networks of economic and political power that animate Asia’s new megacities – is experienced by the inhabitants of these places. The mechanisms of globalisation are woven into the fabric of the city, localised in the practices of everyday life and reflected in the transformation of the built environment. Looking back with hindsight at Girard’s early photographs of Vancouver’s downtown port district, his images are a timely record of social and economic patterns that were set to vanish as the city was transformed from a working port town into a hub for global capital flows.

Returning to Vancouver in 2011, Girard was struck by the way that the city had changed. In November 2015, we spoke about his early work, about learning the craft of photography in 1970s Vancouver, and about the challenge of making pictures in complex environments.

ES: Some of your early work has already been published in In the Near Distance (2010), but I understand that there’s another book coming out.

GG: That’s right. Misha Kominek is doing a book about the early Vancouver work. Some of that work from that period, was included in In the Near Distance, but the pictures in the new book will all be pictures that haven’t been published before. The working title is Under Vancouver.

Blank Sign, 1981 @ Greg Girard

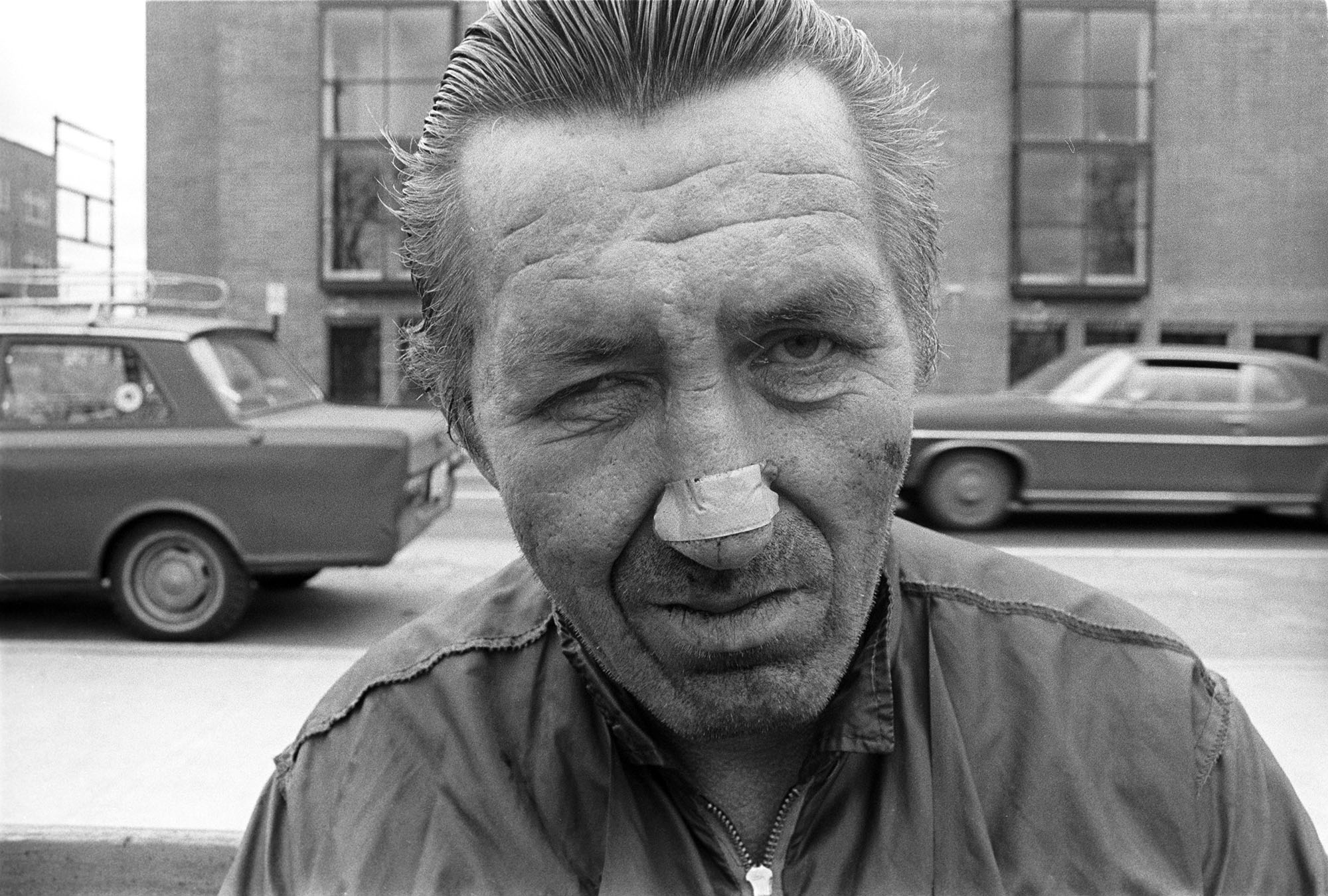

Band Aid, 1975 @ Greg Girard

“When you’re younger you think that the world is a certain way, and that it won’t ever get any different; eventually you become aware that things are constantly transforming.”

ES: Tell me about the decision to publish a new body of work from that period. Can you talk a bit about the two books, and about the distinction between them?

GG: I had emailed Misha some pictures, scans of vintage prints made in the mid-1970s. Some pictures I hadn’t looked at in a long while. He asked to see more and so we started looking at things and he suggested to do a book together, just on the Vancouver work.

Misha published In the Near Distance almost five years ago now. At that time I was still living in Shanghai, and moving back to Vancouver about three years ago, the city is a different place now. Vancouver was a working port town back in the 1970s, and it wasn’t on the international map, it wasn’t really connected in the way that things are today. In Vancouver’s case, the city has become better known than other cities of its size and importance, because of the access to Asia from here, and the way it’s become a popular destination for people and capital. That’s really changed the nature of the city. When I grew up here, it was a working port town, and all the streets downtown ended at the harbour. That working port was very much a part of the feel of the city, at least to my mind. One of the big changes for me, moving back here, was the way that the city is now cut off from the working port. But that’s probably true almost everywhere else as well, partly in response to 9/11, where every port now is like an air cargo terminal, it’s fenced in and monitored, and there’s no public access any more.

ES: It’s probably also got to do with the sheer volume that comes into most of these ports. Certainly in London, none of the cargo that comes in ever comes anywhere near London any more, because it simply couldn’t handle it. All of the old warehouse districts are now occupied by condos. The actual warehousing and cargo shipping takes place much further out along the Thames Estuary.

GG: That’s right, and the containers go on to rail cars, and you never see it any more, it all happens out of sight. Indeed, all of those cargo ships used to come right up the Thames. So I think partly it’s just the evolution of the industry. That separation was kind of finalised post 9/11, when everybody secured their ports, and if you had no business there, you weren’t allowed in.

ES: When that changed, obviously, the environments that you were shooting in – the hotels, the bars, the shabbier districts that the sailors would frequent – all of those went as well.

GG: Yes. The turnaround of ships became much shorter; crews didn’t have as much time to spend in port. So that integration of the port and the city started declining and, especially with containerisation, the nature of long shoring activity changed too, so you had less and less services and bars and other businesses that served people working at the port.

ES: In In the Near Distance, there are images from a lot of port cities – San Francisco, Vancouver, Hong Kong, Shanghai. Was it your early experiences of Vancouver that got you interested in port cities, and in that phenomenon?

GG: Not consciously. They were places, those parts of the cities, that looked a certain way. Those parts of the city always kind of lagged a bit. When I was photographing in the 1970s, I suppose things looked more or less the same as they did in the 50s – things didn’t get updated, and I guess, even now, there’s always that lag.

ES: I know what you mean, and I think about this a lot. When you’re younger you think that the world is a certain way, and that it won’t ever get any different; eventually you become aware that things are constantly transforming. But the 1970s were a period when globalisation started to take off, and when change became so rapid that the idea of things staying the same way forever became impossible to hold onto. I’m from Vancouver as well, and I have a lingering impression of the way that city looks. That was one of the reasons that I was so interested in the work, because I recognise these places, I know how these places feel, because I grew up there, or in places very like them.

GG: I grew up in Burnaby, which is a suburb of Vancouver. Going from Burnaby to Vancouver is a distance of about 8 miles, but when you’re young, it’s a bigger journey, everything looks different. That was one of the first things I did when I got my first camera, to start photographing downtown; it seemed the most interesting, the most different.

ES: You were pretty young when you started doing these nocturnal ramblings – 17, 18? How did you get started in photography?

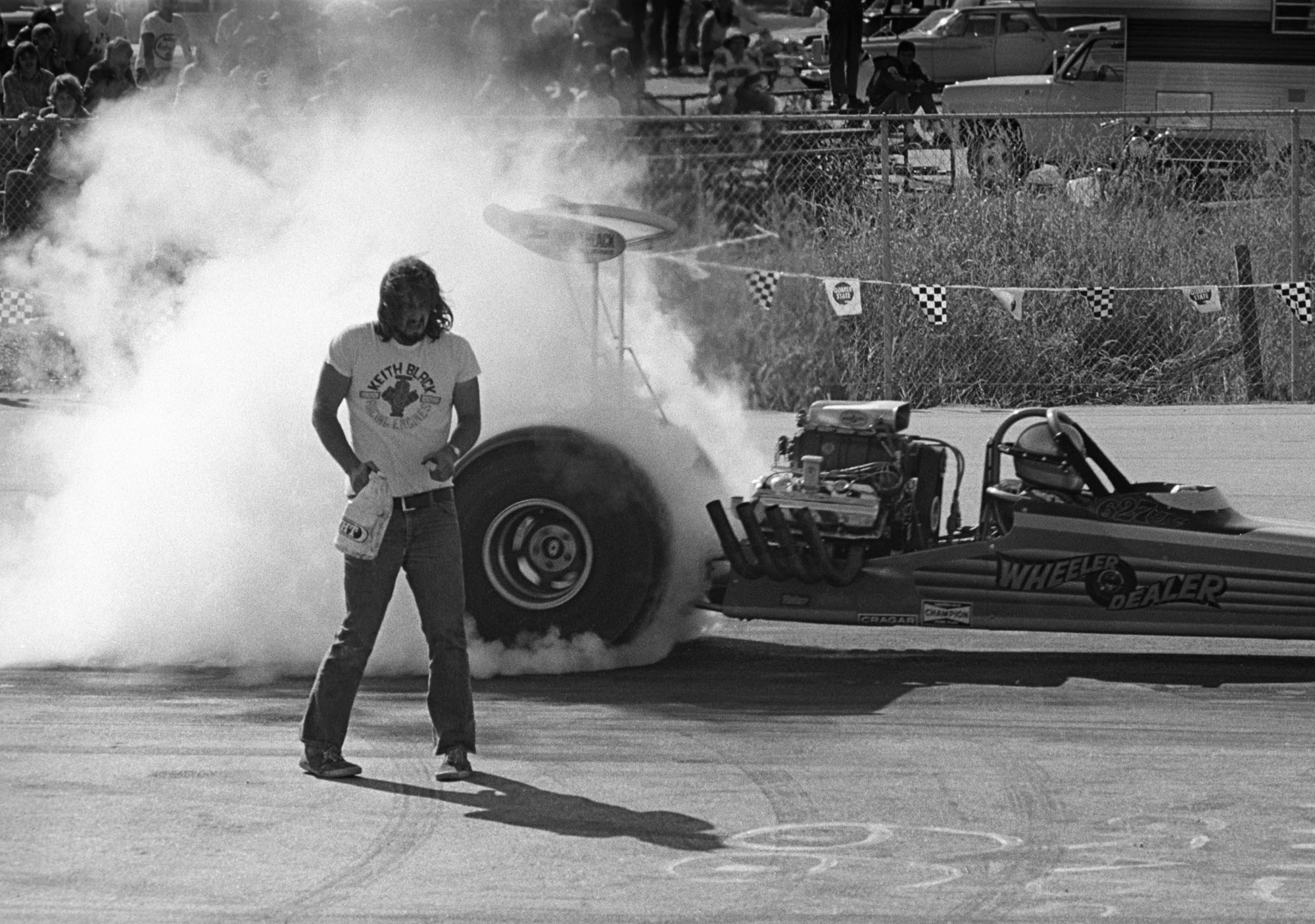

GG: Yes, Exactly. I had saved money and bought a Canon SLR – the most stripped-down model you could get – and started taking pictures, including pictures at night, and over time tried to refine it, the night pictures. It took a while, but that initial adventure, being in a new place, was something that propelled me. In those days I did a mix of black and white, never really having been told that you had to decide between black and white and colour.

ES: You processed all of your film yourself?

GG: Yes, and some colour transparency developing as well.

ES: Cibachrome?

GG: That’s right.

ES: So you didn’t have any formal instruction in photography? What got you interested in it?

GG: The first pictures were made when I was about 14, borrowing my father’s camera. In high school I took a graphics course, and part of the graphics course was learning to process film. The teacher there was a pretty keen photographer, in an interesting way, more expressive rather than camera-club kind of stuff. He was more of an artist – he was a good technician but also encouraged the expressive part of it. That was the first time I had conversations about pictures, looking at them and talking about them, in high school. That was formal in the sense that it was in school, but after that no further formal education.

Waterfront, 1981 @Greg Girard

Mission Drag Strip, 1973 @ Greg Girard

Hong Kong Harbor, 1962 @ Eliot Elisofon

“I don’t know. How do you explain the reasons why you’re interested and what you’re interested in? Where did it come from? I don’t know. You can chart the evolution of it, but that initial thing, I don’t really know.”

ES: Do you remember what sort of work you were looking at very early on?

GG: You know, there wasn’t much in those days. The photography magazines were mostly technical magazines, and places to advertise products. You’d have reviews of the latest cameras or lenses, and then you’d have a portfolio by Diane Arbus or Lee Friedlander, or Garry Winogrand. That was the only place you would really see photography. Photography galleries hadn’t arrived yet – I think the first one in Vancouver was Novus, which opened in the late ‘70s. You didn’t really see it.

ES: Things were very similar in the UK – limited availability of magazines, and no galleries until the 1970s. And taking urban and suburban landscapes, as you were, certainly wouldn’t have been seen as ‘camera club’ photography. Being in British Columbia, you’re surrounded by the most incredibly camera-clubby landscapes, aren’t you? So the decision not to engage with that, that’s quite a mature one for somebody who’s just starting out.

GG: I don’t know. How do you explain the reasons why you’re interested and what you’re interested in? Where did it come from? I don’t know. You can chart the evolution of it, but that initial thing, I don’t really know. I went to Asia in 1974, and that was the first trip outside of North America, and it was a big photographic adventure, as well as a personal one. I think it was all part of trying to get deeper into the place you’re at, in a way that shows what’s there. You asked about influences – there was a series of Time-Life books on photography, with these silver-grey covers and a black spine, I’m not sure if you know the ones I’m talking about?

“I went to Asia in 1974, and that was the first trip outside of North America, and it was a big photographic adventure, as well as a personal one. I think it was all part of trying to get deeper into the place you’re at, in a way that shows what’s there.”

ES: I do. I think my Dad had a few of them.

GG: I’d borrow those from the library. They came out in the early 1970s, and there was The Camera, and there was one on travel – I’ve still got them here somewhere. I started buying them some years ago on Amazon for a dollar, next to nothing. I was actually looking for an early photograph I’d seen, that I thought at the time was really powerful and interesting. I eventually did track it down from the travel edition of that series – it’s called Travel Photography, and it’s all about how to take good pictures in foreign places. You’ve got framed things with arches, and a lot of very conventional techniques for doing conventional pictures. I’d gotten interested in Asia at this time, reading different things, and in this book, there was one picture of Hong Kong harbour, taken in 1962, I think, by Elliot Elisofon – he’s largely forgotten now, but he was photographing for Life magazine in the 60s. The photograph shows these cargo junks in the middle foreground, and behind them you’ve got the 1962 Hong Kong skyline, with illuminated signs for Sony and Pepsi-Cola, and things in Chinese. I thought it was really great, this way of including everything in the picture, instead of, for example, just focussing on the exotic Chinese junks and leaving out the Westernised skyline. It’s perhaps difficult to imagine how this could have been an adventurous picture back then, but to me it was. I’d never seen a photograph that seemed to balance so many things, things that weren’t conventionally photogenic, including the muted colours and the approaching darkness on an overcast day. The tension in the picture seemed created by what he carefully chose to include, and it was so clearly a visual statement. I thought it was a pretty radical picture at the time. It made me want to do something like that.

ES: I recognise some of Elisoson’s work – my parents were very fond of the Time-Life series, so a lot of these images and that style are very familiar to me. I was thinking as I looked through your early work that they are very complex pictures – they’re visually very detailed, there’s a lot going on. For someone who has allegedly not had a lot of training in photography, it takes a lot of skill to put that much in a picture and have it all still hold together. I was struck by that when I first started looking through the work – the sophistication of some of the pictures, particularly those taken in Hong Kong. It’s such a visually complex environment anyway – I’ve been there five or six times now, and the overwhelming feeling is of simply not knowing where to look. I found it a very difficult environment to photograph in. Your early work also seems to mix what I guess we’d now separate into a couple of different genres – a black-and-white ‘street photography’ aesthetic, which is quite raw, and also a ‘night photography’ aesthetic, where you’re working with very sculptural shapes and colours and shadows that are cast by the light.

GG: Hong Kong is really stimulating. It was the first foreign place I went to. I travelled by ship from San Francisco. Even in those days it was hard to get passage on a freighter, they’d stopped carrying passengers, but I really wanted to travel by ship, so I found a Philippine freighter company that still took passengers, they had about six cabins. I sailed from San Francisco to Hong Kong.

ES: How long did that take?

GG: Eighteen days. Seeing the Hong Kong skyline for the first time is exciting, just as it is today -that much density, that much height on a skyline. Today it’s magnified by ten times, but it still registered that way back then. As for making pictures, especially once I started living in that part of the world, the guiding thing was that the pictures would have to be interesting to people who knew the place and lived there, rather than interesting to the folks back home, as it were. If you’re living there, then you’ve got to try and be equal to what everybody already knows about the place.

ES: Avoiding the temptation to exoticize.

GG: I think so, yeah, even though you’re living within something you don’t fully understand.

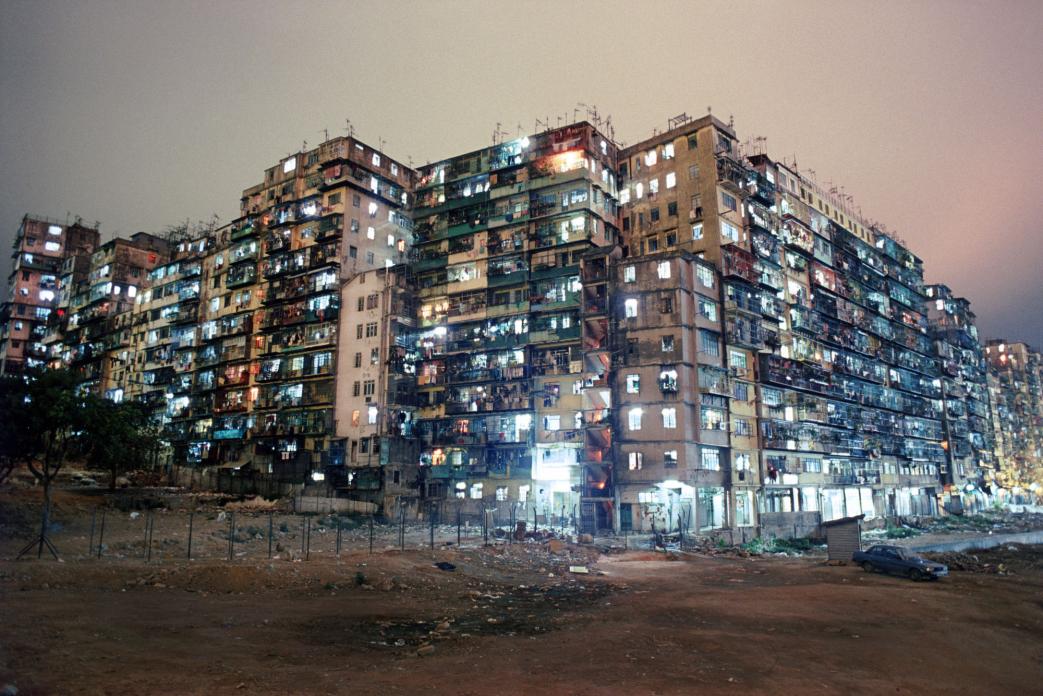

Watching aircraft land at Kai Tak Airport from Kowloon Walled City rooftop, 1990 @ Greg Girard

Kowloon Walled City Night View from SW Corner, 1987 @ Greg Girard

“Eighteen days. Seeing the Hong Kong skyline for the first time is exciting, just as it is today -that much density, that much height on a skyline. Today it’s magnified by ten times, but it still registered that way back then.”

ES: Your work on Kowloon Walled City is remarkable.

GG: Thank you for saying that. But, I mean, how could you mess it up, a place like that? Though, in a way, I feel almost did. I had just started working as a photographer for a magazine, and I was extremely happy about that, to be able to start making a living as a photographer. But what it meant was that, in a way, I stopped doing my own pictures when I started making pictures for the magazines.

So by “mess it up” I mean by stylistically having done it in a conventional photojournalistic approach – that kind of wide-angle, fly on the wall view of life. Nowadays, I almost prefer my co-author Ian Lambot’s pictures to mine from that series – his are a more traditionally architectural examination of the place, cooler, more objective. My pictures dealt a lot more with the activities within the place, and certainly more with the people. But I was starting down this new road that I was very happy to be on, making a living in photography. I have no regrets about it. But it was different than what I did before, and different from what I would end up doing later.

Having said that, photographing for magazines also meant that I had to learn how to use some basic lighting techniques, and the Walled City pictures benefitted from that: for example, using portable strobes with an umbrella or soft box to light the interiors and make pictures of people.

ES: What magazines were you working for during that period?

GG: I started off with something called Asiaweek, and was employed by the magazine for a year, and then quit and went freelance, and started working for everybody – Time, Newsweek, Fortune, Forbes, and The Guardian, and Paris Match – you know, pretty much everybody.

ES: The early work is incredible work, historically as well as photographically. There’s so much interest in the 70s at the moment, retrospectively, and I think it’s not just about the way that the photographs look. It’s also about that particular period in human history where, as you were suggesting earlier, things start to shift from being local to being global, and the stasis in the way things look and the way places are, and the way they feel, that all starts to change very rapidly. Were those things on your mind when you thought about republishing some of the earlier work?

GG: It was unsettling coming back here. The city had changed a lot, and people here find some kind of pride in knowing that Vancouver is a globally connected and attractive place, and better known than it used to be. I find it all a bit disappointing though – the glass towers that Vancouver now seems to be known for, I don’t see anything particularly interesting about them. I don’t mean that in a kind of retrograde way, or missing the old Vancouver, I just mean that these are everywhere, so why would they be interesting? For me, the biggest change was, as I was saying earlier, this whole disconnection from what Vancouver used to be, especially on the waterfront. Also, most working class neighbourhoods have almost disappeared. The working class can’t afford it any more. That hollowing out has certainly happened in other attractive cities as well. The places that used to be working class, they’ve mostly gentrified, or, in one particular area, completely gone through a hole in the ground, have become dysfunctional almost. Vancouver is a little bit unusual perhaps, in the way that there’s a place for people who are really struggling and can’t join the working parade. You’ve got a few blocks here that are really quite surprising.

ES: The last time I was in Vancouver, I guess it must have been about five years ago, in the core of downtown, there is a ropey little district that feels completely out of context.

GG: That’s right. It’s another world, really, about six square blocks, most people simply avoid it. But now gentrification is happening there as well. Vancouver, and Canada, has a lot of tolerance for things that might not exist elsewhere, they just wouldn’t happen. There’s a lot of drug use, mental illness, and social problems that are kind of contained in this area. There are a lot of social services to look after people, but the human cost of some of this hollowing out is very evident here. But back in the ‘70s, this neighbourhood was working class, and tough, and full of restaurants and shops, pool halls and pawnbrokers, very much alive. It was a part of the city that Fred Herzog has put Vancouver on the map for. Part of what’s unusual about Fred’s work was the fact that he was using colour at that period, and the technical demands of shooting Kodachrome meant that you really had to know what you were doing. And he has a great eye. My pictures, obviously, are a little rougher, you could say. I was photographing maybe a bit of a darker side of town. And Fred’s pictures are from the ‘60s.

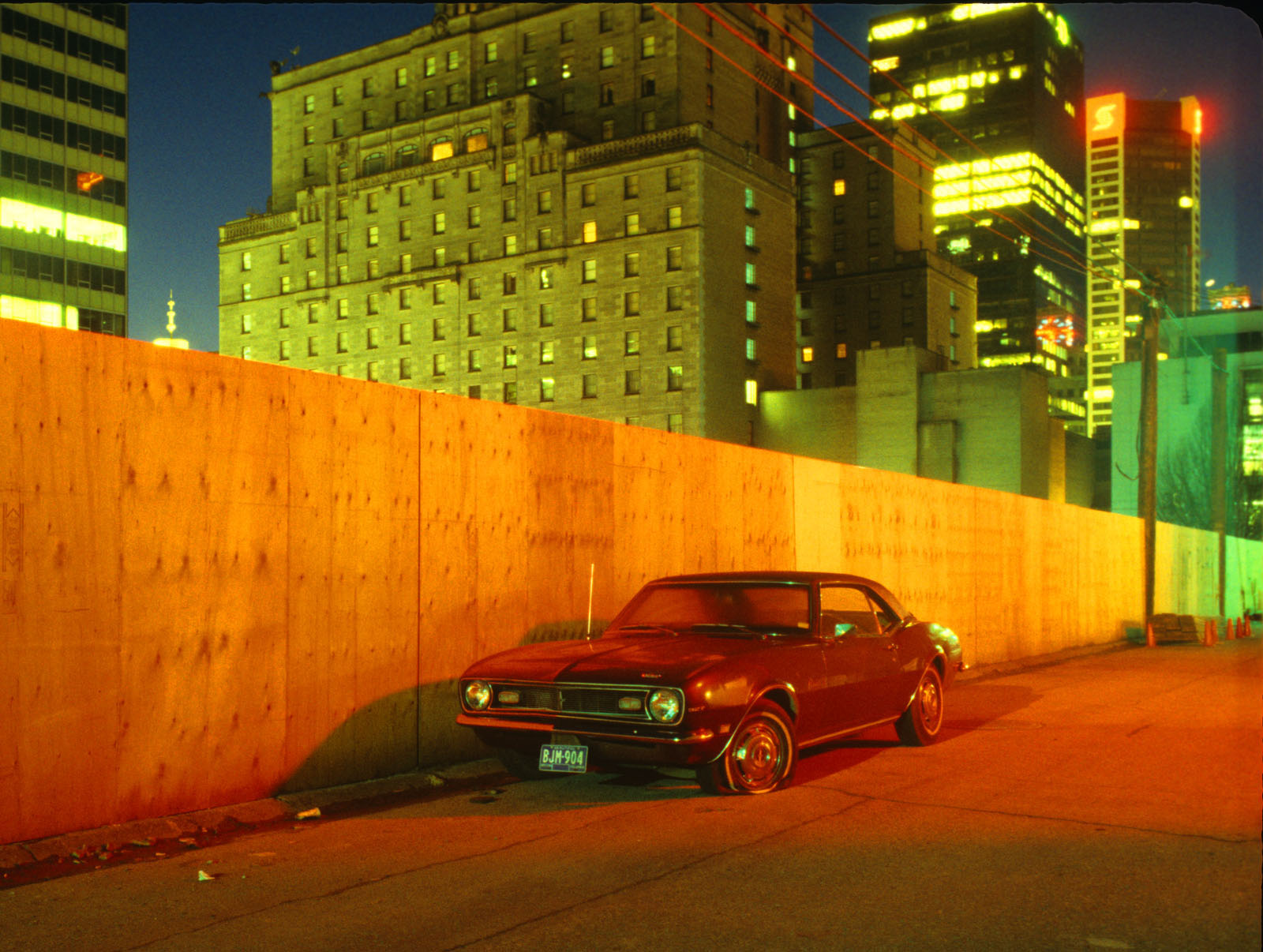

Red Camaro, 1982 @ Greg Girard

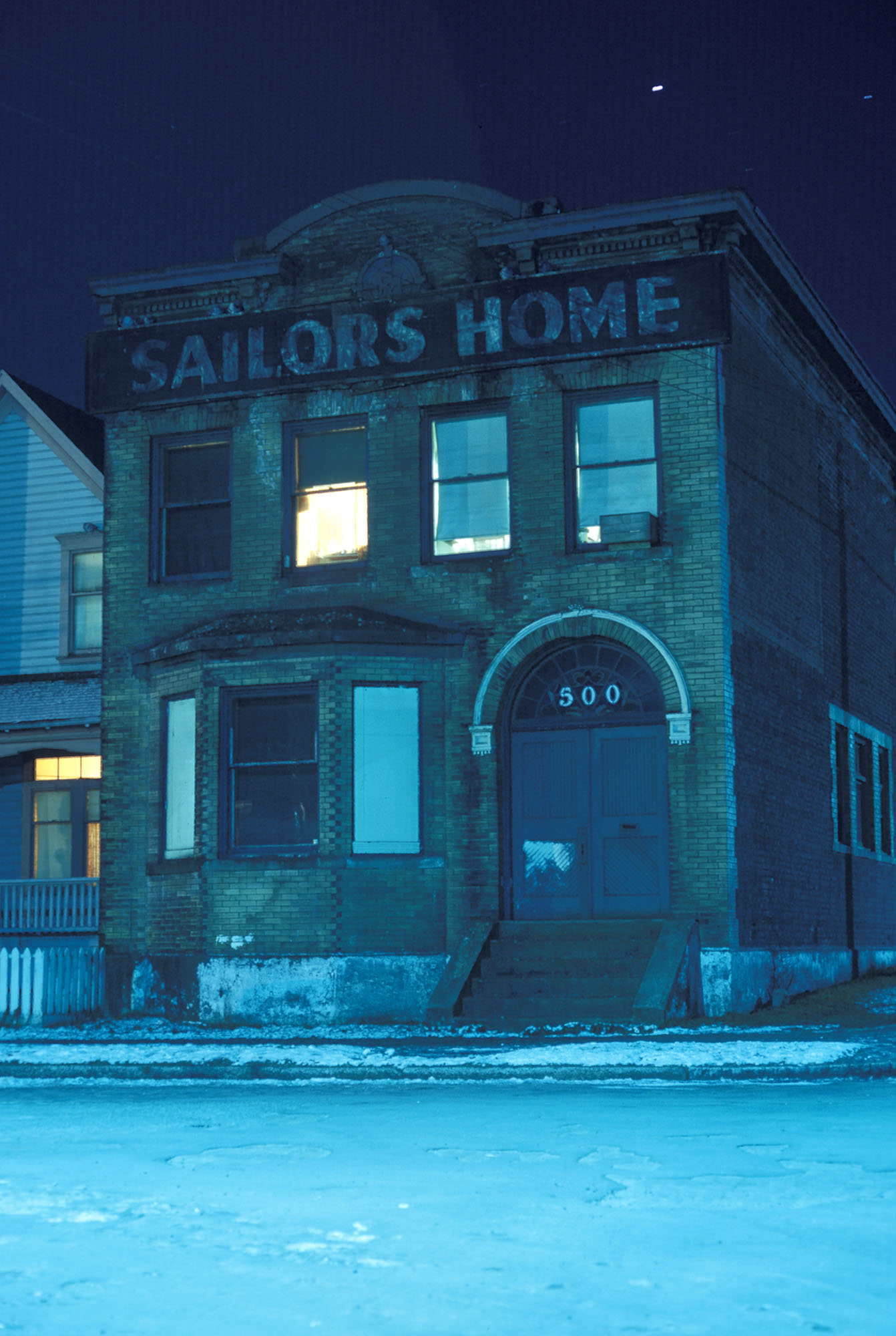

Sailors Home, 1973 @ Greg Girard

“The evolution of one’s craft involves the tweaking of it, looking at what artificial light does on different kinds of film. There’s that kind of adventure with the material.”

ES: I find his pictures much more formal. You could tell that you were looking at people like Friedlander – pictures that were just that bit more complex, dense, packed from corner to corner with information. But mixed in with that kind of work are these incredibly spare, almost colour blocked images taken at night – I’m thinking of images like ‘Camaro in Alley’. What was it about the night? Was it knowing how those colours were going to be rendered on the film that interested you? Shooting at night, the temptation obviously is to treat things in a more formal way. You can’t get that clarity of detail when you’re working with limited light.

GG: I’m sure a lot of it has to do with not knowing exactly what you’re going to get. The evolution of one’s craft involves the tweaking of it, looking at what artificial light does on different kinds of film. There’s that kind of adventure with the material. There were a lot more film choices available then, and they all did slightly different things, or very different things. That was part of the adventure.

ES: Was it also the environment itself? Obviously for someone from Burnaby, coming in from suburban areas like that, downtown always feels a bit dangerous, and wandering around at night has this sense of something that’s dangerous, and tempting in that sense. I wouldn’t go so far as to call it thrill seeking, but certainly seeking out a different kind of experience.

GG: Absolutely. Even in high school I would occasionally, on weekends, check into a hotel downtown and photograph people. The last year of high school, and then later as well. I ended up, in the late ‘70s, living in a hotel downtown, on the edge of Chinatown. Those days, in Vancouver anyways, there were so many of those cheap hotels, single room occupancy hotels that have now become part of the government housing program, so you actually can’t stay in them, you can’t in walk off the street – you would need to be on social assistance to be a tenant there. That whole world of cheap hotels has mostly gone.

ES: Is there any element of nostalgia in looking back over this work? I don’t mean that in a sentimental way.

GG: There probably is. I think a lot of people have heard about that period in Vancouver, and there is maybe an interest in seeing more of that. I think every city is interested in itself, and its own history, and that’s certainly true here as well. For myself I don’t feel nostalgic looking at the photographs. Every picture that’s dated in that way has, or could have nostalgia attached to it, but for me, I don’t look at them and wish things were the way they used to be.

Dr Eugenie Shinkle is a Reader in Photography at the University of Westminster

(All rights reserved. Text @ ASX and Eugenie Shinkle. Images @ Greg Girard.)