”I go to places and I have the belief that if I can photograph well, the places will educate me to things I do not know about them.”

Sunil Shah with John Gossage, ASX, November 2015

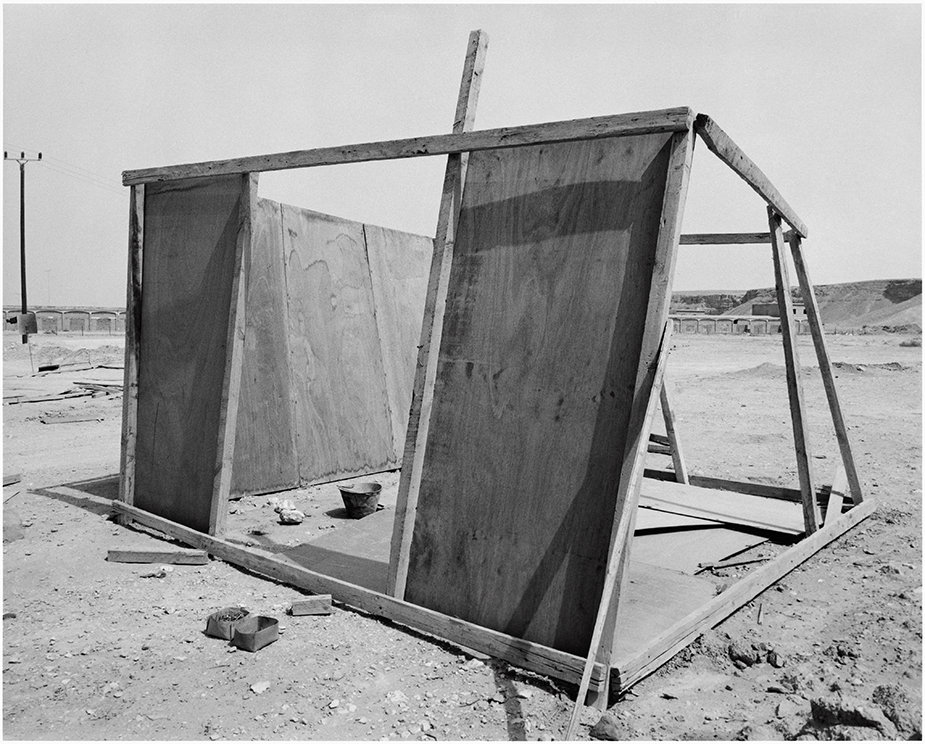

In light of recent conflicts in and around the Middle East, I find it hard not to read images of the region in the context of global politics and social struggle. One example is a set of photographs made by John Gossage in his book, ‘Nothing’. I imagine the featured desert terrain as a desolate, post-combat landscape. There were people here, evident through the remnants of ancient and recent civilizations, but now the land appears forlorn and deserted. Could this be Syria or Iraq? or a meditation on the aftereffects of war? My imagination replays a semi-fictional, socio-political scenario that steers my perception.

@ John Gossage

In 1985, John Gossage found himself in Saudi Arabia. A chance suggestion to a friend resulted in a personal invitation from Prince Abdullah bin Faisal bib Turki Al-Saud, to visit and take photographs.

As a guest of the state, his guides were instructed to respond to his every whim, he could go anywhere. However, Gossage is unconventional, his approach, apolitical and firmly based on the experiential. On his request to be taken out into the desert, he was told there was nothing there, to which Gossage had replied, “Yeah, that was sort of what I was looking for”.

@ John Gossage

The photographs from that trip lay dormant for almost 30 years, until last year, when Gossage looked at them again. As is central to his work, they became part of a photobook project and it was in this way he was able to resolve the work. Gossage’s photographs are about what he found on the edge of the desert looking out at nothing, and nothing more. I discovered this when I spoke to him about the book:

Sunil Shah: The title invokes wonder and ambiguity. Although a reference to the opening exchange between you and Prince Abdullah, it seems to relate to nothing and everything that fills the desert. The locations in the book appear to be on the periphery between urban life and the emptiness of the desert and I feel this is the territory you explored. How did you approach this work?

John Gossage: I go to places and I have the belief that if I can photograph well, the places will educate me to things I do not know about them. Going to Saudi Arabia, I just tried to photograph anything that seemed of importance to me. It was not based on fact, it was based on instinct and the whole thing was shot in around 3 weeks. I am almost at the whim of the place where I’ve decided to make the pictures. The intellectual part of it came in the contextualizing of the pictures. How the pictures relate to each other is the point at which I consider things, not in the shooting.

@ John Gossage

SS: Your approach to photography is unconventional, especially in terms of the documentary tradition, which you openly shun. I feel you deal more with the poetics of place than the politics of place. Now, I’m going out on a limb to suggest this… In light of how the middle east is represented in the media these days, in terms of Syria or the War of Terror, is there political interpretation that can be read into this book and was there ever a consideration of the ‘political’ in choosing to release this book now?

JG: There was no consideration of the political or any reason to release the book now particularly. It was really the sense that I might be able to find my way through these pictures – in a way that made sense to the original experience. Obviously, I knew about all the conflict and contextualization of what has occurred since. Actually, I never consider any political beliefs as an artist to be effective, after living here (Washington DC) for so many years, I see how tough it is to get things to work. It is almost like we make political photographic books speaking to the already committed. It doesn’t seem to move the needle much towards making a better world, so I have a really dubious sense of that kind of importance, that wouldn’t motivate me in general.

@ John Gossage

@ John Gossage

“There was no consideration of the political or any reason to release the book now particularly. It was really the sense that I might be able to find my way through these pictures – in a way that made sense to the original experience”.

SS: The book is separated in 3 parts, which are numbered to guide the viewer. Yet holding the book out it is possible to simultaneously thumb through the first two outer parts simultaneously and disrupt the conventional sequence by being able to open up different spreads together. Therefore, the book can be leafed through a prescribed sequence or be open to multiple layouts. What narrative exists, if any, and what does this format mean to you?

JG: There is no numbering as such, they are separated by one, two and three dots which is trying to be less emphatic about a narrative one should follow. I’ve seen people use the book which is always fascinating for me and people use it differently. It is a book that does not have any implied narrative as such. What I try to do is make objects of fascination. A photobook, as I understand it is, if you get the prescribed message in the first one or two viewings, it is not an interesting book. If you get it right though, they keep having this lure that you’ve never quite gotten the whole story and you want to continue to return to them.

@ John Gossage

SS: The inclusion of the passport page is an image that stands out and gives us further context for your visit in Saudi Arabia. With the grey cover, I think it also adds to an archival, document feel to the book. It takes us back to your visit from the present, a reminder that this was a brief visit a long time ago. How does that time relate to you now? Or is the book fully rooted in the present?

JG: I remember being there and it was a fairly memorable trip. The world was the world in the pictures, so it was a book of that idea. If I was to think about it, it was a book I did last year, because I was living in the world of the images. It is long enough ago that the memory is somewhat faded. I remember where I was when I shot some of the pictures and some, I only generally remember – Riyadh, Jeddah,Tabuk. If the pictures still didn’t have life in them for me, I wouldn’t have done the book. However, it was a life that was present and immediate and this informed editing of the pictures.

Gossage_15, 6/27/14, 12:00 PM, 16G, 4556×5083 (1068+1602), 75%, Custom, 1/40 s, R48.6, G32.5, B56.1

SS: At the book’s centre, the double-sided panoramic images open out. It takes us back to the idea of Nothing. In a recent interview you mentioned how photography is limited to the frame and how a single image is not able to tell us what is to the right or left of it, what is behind it and when it does it often shows very little that is remarkable. Is this image of the desert an extension of the idea that photography is incomplete, yet a desert is the ultimate physical incarnation of both everything and nothing?

JG: It was a simpler thing for me. If you get to a certain point in the desert where there is no feature on the horizon or the horizon is without anything in the distance, you have the illusion you can see the curvature of the earth. We were driving somewhere in the desert and I asked the driver to stop, and I stood there for a while. I then just decided, with a normal lens, I would document 360 degrees. It was not a particularly adept panorama. So, now I’ve got everything in and I haven’t left anything out and there is still nothing there. That was a strange place to be in the world. I work off experiential stimuli more than concepts and it was an experience that was important to me.

“I never consider any political beliefs as an artist to be effective, after living here (Washington DC) for so many years, I see how tough it is to get things to work.”

SS: I wanted to ask about the ‘unconscious’ or the way in which the act of photographing or the act of viewing photographs can be completely intuitive and at some stage in that process, something resonates and makes sense, even fleetingly. I feel your work very much deals with this concept. Is this an inherent part of the human psyche that you identify with yourself and could this be how audiences engage with your work too?

@ John Gossage

@ John Gossage

JG: My pictures are obviously what they are, in other words, they are clearly rendered places, things and people, there’s no masking of them, no obvious attempt to make them into metaphor. They are what they are. Given that grounding, which I believe photography’s strong suit is, the fact that we can still convince people that these are pictures of actual things in the real world, that’s all we have. We don’t move, we don’t sing, we are not objects in the room like a great painting is, so the only thing we have is a little portal into another time and another place. So what I try to do is make the pictures understandable that way. It just works, I know how to make John Gossage pictures.

JG: I just go out and things fascinate me in the world that I haven’t even thought about before I get there.

JG: I keep learning things.

John Gossage

Waltz Books

Sunil Shah (b.1969) is an artist and curator based in Oxford, UK. He is interested in the politics of photographic representation and conceptual post-documentary practices with relation to history, memory and identity.

(All rights reserved. Text @ Sunil Shah and ASX. Images @ John Gossage and courtesy Waltz Books.)