Often blurred and seeming to blend into interiors which fail to contain her, Woodman’s photographs evoke a haunting, haunted world wherein her own physical self appears to vanish—or emerge—before our eyes.

By Katharine Conley, Dartmouth College, excerpt from Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 2:2 (2008), 227-252

Throughout her photographic series from the 1970s, Francesca Woodman maps her interior space, revealing the physical dimension of the psychic. Often blurred and seeming to blend into interiors which fail to contain her, Woodman’s photographs evoke a haunting, haunted world wherein her own physical self appears to vanish—or emerge—before our eyes. These images suggest that within her own psyche her sense of self was permeable. Yet unlike her predecessor in surrealist photography, Claude Cahun, Woodman’s sense of a changeable self was not expressed through playful disguise. Instead, through the blurry images and the captured movements, she reveals an inner cartography that circles around variations on the same evasive persona. Her series are made up of sequences shot mostly in old houses and usually featuring herself, though she rarely shows her face. Their titles, Providence, House, Space2, and On Being an Angel, come from their locations and from her experiments with the body in space and the limits of everyday reality. Her work could be seen as a personal meditation on the opening question of André Breton’s Nadja—“Who am I?”—a book Woodman reportedly read attentively.1 It shows how effectively this young American’s practices intersect with Surrealism, simultaneously lending focus to Woodman’s work and showing how surrealist principles have persisted past World War Two, particularly in the work of women artists and writers like Woodman.2

Woodman’s early life was spent in Boulder, Colorado. Her artist-parents—her mother was a well-known potter and her father a painter—took her on regular trips to Italy, where she returned as a college student. After studying at the Rhode Island School of Design, she spent a summer at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire, the oldest artists’ colony in the United States, and moved to New York City, where she lived until her death by suicide in 1981 at age twenty-two. Most of her photographs were taken when she was an undergraduate. Over 800 remain archived, from her earliest self-portrait shot when she was thirteen in Boulder to photographs taken shortly before her death in New York. Many of these were created as homework assignments, what Rosalind Krauss calls her “problem sets,” explaining how Woodman “internalized the problem, subjectivized it, rendered it as personal as possible.”3 Chris Townsend has convincingly established Woodman’s credentials as an accomplished practitioner of photography within the post-surrealist and post-minimalist traditions, an artist who used technique effectively to disturb the typical parameters of space and time of her medium. Yet her images also tell stories, and it is their narrative function as much as her practice that links her directly to surrealist precedents in ways that extend the movement into the 1970s, despite its fifty-year distance from its development in Paris by a group including Breton, Robert Desnos, and Louis Aragon, together with such artists as the American photographer Man Ray and the German painter Max Ernst.

Fig. 1. Francesca Woodman, “then at one point i did not need to translate the notes; they went directly to my hands,”

Providence, Rhode Island, 1976. Courtesy of George and Betty Woodman

Three of the Providence series have captions linking photography with piano playing, establishing a correspondence between one medium and another and highlighting the way in which her series ought to be read linearly like music.

Narrative Pictures: The Stories In-Between

Woodman’s serial images encourage the viewer to link them together because of the way this technique, as Margaret Sundell notes, “pushes the limits of the photographic frame.”6 They do this both in series and as individual shots. The photographs in which Woodman shows her own body in movement challenge photography’s link to the real as a familiar, knowable entity, in the same way that Breton’s theories challenged the representational aspect of words. Just as Breton sought to tease out the uncanny quality of the unconscious through the automatic process, Woodman used her photographs to defamiliarize her own body within familiar spaces, to make it appear ghostly while still very much alive, since the emphasis tilts towards emergence and creation over disappearance. She used her photographs as a kind of writing, aware of photography’s indexical properties, its persistent and tangible reminder of the precise instant in the past when the shutter was depressed, as well as its elegiac quality and capacity to communicate ghostliness—of the possible psychic coincidence of past and future in an intensified present moment.7 Photography is inherently more like writing than like painting, particularly in the form known as the photogram—popularized by Man Ray as the “rayograph,” involving the placement of objects directly onto a light-sensitive surface. Literally “light writing,” the photogram comes close to the older term calligram which, Foucault argues, “aspires playfully to efface the oldest oppositions to our alphabetical civilization: to show and to name; to shape and to say; to reproduce and to articulate; to imitate and to signify; to look and to read.”8

Jacques Derrida, who has written on the photogram, poses a similar opposition between speech and words in “Force and Signification,” where he describes poetry as having “the power to arouse speech from its slumber as sign.”9 The implication is that poetry allows signs to say more than the words that contain them, partly through the animating quality of their juxtapositions—the in-between spaces that Foucault ascribes to Breton, and that I am ascribing to Woodman’s series. Krauss also underscores photography’s indexical quality by suggesting that photography shares in the immediacy of the “raw and naked act” of automatic writing because it presents “a photochemically processed trace causally connected to that thing in the world to which it refers in a manner parallel to that of fingerprints or footprints or the rings of water that cold glasses leave on tables.”10 Furthermore, Krauss argues that through framing, or through the positioning of the image in space, photography introduces the sign that can move from text to image to body.

The series that seems most like a repository for Woodman’s working ideas during her undergraduate years takes it name, Providence, from the city where she went to college. To the extent that this title also reflects a play on the word providence, defined as “being cared for by God,” Woodman shows her sense of humor, since most of the photographs are situated in a house in a state of utter dilapidation. Three of the Providence series have captions linking photography with piano playing, establishing a correspondence between one medium and another and highlighting the way in which her series ought to be read linearly like music. Each note, each phrase, interconnects with those surrounding it, the way Woodman’s bodies interact with their surroundings, at times almost animating the interiors where she situates them. Two of these captions state: “And I had forgotten how to read music”; and “I stopped playing the piano.” One shows a clothed woman with only the lower part of her face visible, holding a dried leaf in an outstretched hand. The other shows a chair beneath a mirror and a heart-shaped pincushion hanging on a peeling wall. These two images, which do not relate visually to music, sustain music nonetheless as the underlying reference in the third, most striking photograph of the three, which is annotated with the handwritten caption: “Then at one point i did not need to translate the notes; they went directly to my hands.” The notes here clearly refer to music yet also refer to written notes, the kind that pass through the body when writing automatically, a practice described by Foucault as “that raw and naked act, [when] the writers’ freedom is fully committed.”11

The passing directly to the hands in this third captioned Providence photograph devoted to music mimics the process of automatic writing, which Breton defined in the “Manifesto of Surrealism” as “[p]sychic automatism in its pure state, by which ones proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought.”12 What Breton leaves out is the body in between the thought and its expression—a body that in Surrealism was usually represented by a woman—as in the anonymous photograph L’Ecriture automatique which adorned the March 1927 cover of the journal La Révolution surréaliste—and to which women gave acknowledgement in their writings and art, as I have argued elsewhere.13 In Woodman’s image and caption “the actual functioning of thought” and the “psychic automatism in its pure state” are not limited to the mind but work primarily through a body that happens to be female, and specifically through the hands, the parts of the body that make writing, music, and pictures. She confirms a comment made by Breton in 1921 that automatic writing was “a veritable photograph of thought.”14

With her caption to this third Providence photograph about music Woodman enacts another aspect of surrealist automatism that is also inherent to experienced musicianship—the ability to produce music on an instrument with which one is so intimately familiar that no thought or premeditation needs to be involved. Desnos, in his automatic performances in the early “period of sleeps” that inaugurated surrealist automatism in the fall of 1922, was reportedly as fluent with his voice in his spoken, hypnotic trances as any player of the piano. Recalling those meetings in a series of radio interviews in 1952, Breton commented that “[e]veryone who witnessed Desnos’ daily plunges into what was truly the unknown was swept up into a kind of giddiness; we all hung on what he might say, what he might feverishly scribble on a scrap of paper.”15 Those who witnessed these public plunges into an altered state or a different world vouch for their authenticity, including Aragon and Man Ray.16 It is also the case that, like an experienced player of the piano, particularly someone adept at improvisation, Desnos’ lifetime of reading and writing and his urgent desire to make art must have informed his seemingly oracular speaking and drawing in Breton’s dark apartment that fall. The same was true for the automatic writings of Breton himself, including the automatic text he co-wrote with Paul Eluard in 1930. When they wrote The Immaculate Conception each session began with an idea out of which their untrammeled writing stemmed; it was prepared yet this preparation did not detract from the automatic flow of mysterious images that resulted from this practice.17

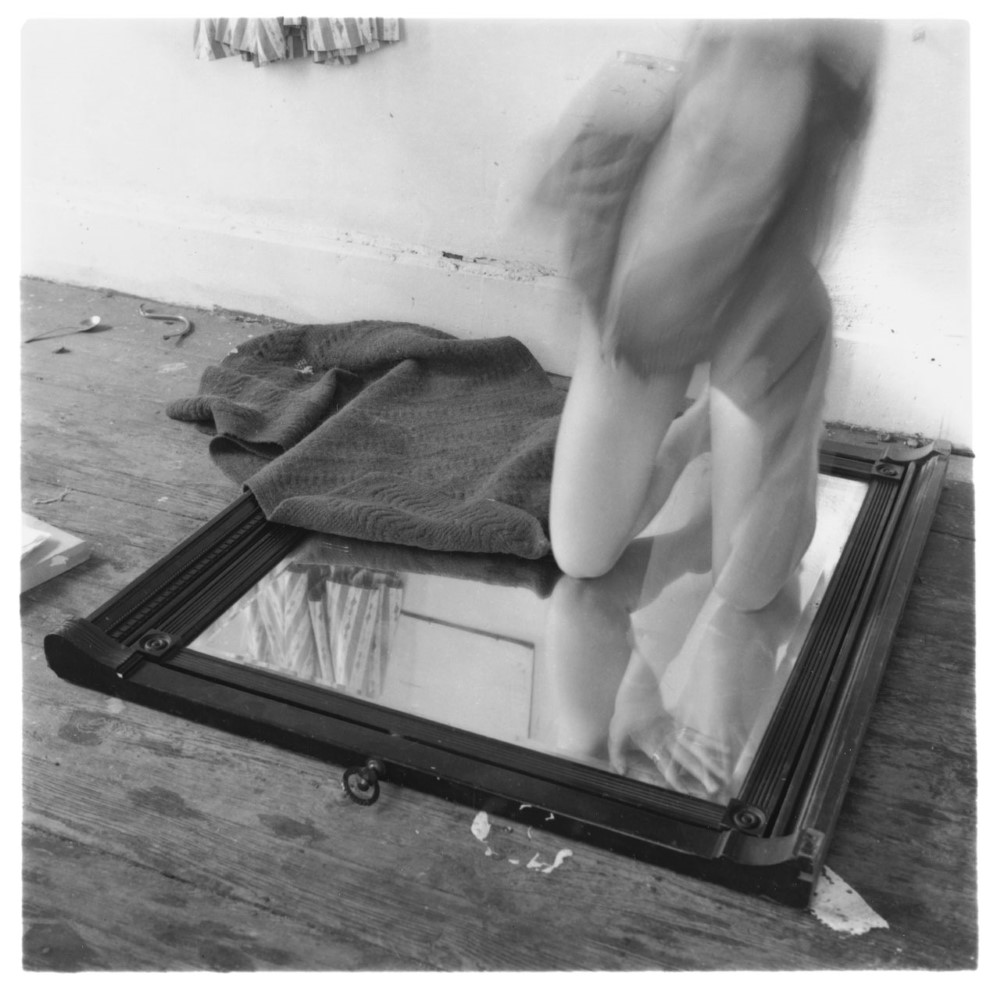

Fig. 2. Francesca Woodman, from Space2, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976.

Courtesy of George and Betty Woodman

The woman stands against the wall facing the viewer and holds the wallpaper over her lower and upper torso in place of Botticelli’s Venus’s hand and hair.

Surrealist automatism could be spontaneous, heightened by the experience of giving oneself free reign to create, while at the same time the resultant work tended to reflect the writer’s or artist’s skill. The beauty of many of Man Ray’s early eponymous “rayographs” no doubt had something to do with his artistic skill. Yet while the practice was premeditated, chance played an important part in the images that emerged from this photographic automatism, just as chance was a key element in Ernst’s early collages and in his creation of the technique of frottage, which involved rubbing objects like floorboards that happened to be at hand. For a young artist like Woodman, who took her training seriously, setting up the work definitely played a part in its success; and yet the set-up involved a practice that promoted a similar receptivity to chance, as in the textual automatic productions of Surrealists like Desnos and Breton, and the visual automatic practices of Man Ray and Ernst. Woodman might not have known the work of Desnos, since translations of his writings have only recently become available, but she definitely knew Breton and she arguably knew the work of photographers linked to Surrealism, such as Man Ray.18 As this particular caption indicates, “then at one point i did not need to translate the notes; they went directly to my hands,” Woodman meant the practice to dictate its own process and to roll out with the fluency of Desnos’ tongue-twisting automatic poems created during the “period of sleeps.”19

The scribbled words at the bottom of this third captioned Providence photograph emphasize the hands and what they do. They also identify the nude figure as a maker, someone whose body acts as a vehicle for expression, who gives her body free rein while retaining observant consciousness of the body’s process, not unlike Desnos’ practices in 1922: “No longer playing by instinct, her body has become an automatic producer of images,” comments David Levi Strauss.20 She embraced the tie of the body in the automatic process to a woman’s body—in other words, while claiming the right to psychic creativity and production predominantly exercised by men in Surrealism’s early years.

As a movement Surrealism emphasized collaborative activity, beginning with the co-writing of the first surrealist automatic text in 1918, The Magnetic Fields, by Breton and Philippe Soupault, and continuing with the early experiments of the group in Breton’s Paris apartment. This emphasis on collaboration also involved the reader-viewer, as Breton’s recipe for how to create automatic writing in the “Manifesto” indicates, since it calls on readers to participate in this new activity. Others besides Breton wrote their own versions of the “Manifesto,” presenting personalized definitions of the movement’s terms, including automatism, from Louis Aragon’s Une vague de rêves and Challenge to Painting to Max Ernst’s “What is Surrealism.” Desnos, through his automatic performances, arguably contributed the most to the understanding we have of the movement founded on a practice involving mind and body making or speaking and thinking; this helped to establish the group’s work as open and inclusive, according to what I have called the “surrealist conversation.” 21

Woodman enters the surrealist conversation through her implicit redefinitions of automatic exploration as occurring in photography as well as inmusical or textual improvisation; she takes a turn examining the prominent surrealist metaphor of the two-way mirror or windowpane, introduced first by Breton and Soupault as the title of the first section of The Magnetic Fields, “The Unsilvered Glass,” and then consolidated in the “Manifesto” with the first automatic sentence ever to occur to Breton as he was falling asleep, “a phrase, if I may be so bold,” he writes, “which was knocking at the window.”22 The phrase itself, “There is a man cut in two by the window,” clearly emblematizes the double awareness of the waking and dreaming mind that the Surrealists sought to capture at its liminal moment, poised between consciousness and the unconscious.23 For Woodman, photographs could function like windows onto the psychic process, expressed in a corporeal language linked to the speaker who, in this case, performed both in front of the camera and behind it. The “notes” of this musical body-ballet “went directly,” as though via automatism—both prepared and free, in the style of her surrealist predecessors—into her hands.

Of Woodman’s three captioned Providence shots connecting the creative processes to one another—music, writing, photography—the last one tells the most coherent story. “Then at one point i did not need to translate the notes; they went directly to my hands” fills in the loss evoked in the notes on the preceding photographs—the forgetting (of reading music) and the stopping (of piano playing)—and substitutes the direct transmission of creativity for loss. Despite the forgetting and stopping, music can still transfuse this body because she has maintained its surrealistic receptivity, its openness to the music of what Breton called the surrealist voice in the “Manifesto,” comparing the first Surrealists to so many “modest recording instruments” attuned to the capture of automatic sounds, words, and images.24 Woodman’s phrase transposes the written note into a visual image that figures a kind of birth—as though she had been born whole and adult into this abandoned space. The photograph portrays the artist as a reversed Botticelli Venus protected by her shell, except that her back is to the viewer and only the beauty of her hands shows. Woodman overwrites the viewer’s knowledge of art to show how she has revised past figurations of woman in a work of art, transforming her from passive model to active creator. One way in which she does this consistently in her work is through the hiding of the model’s face, thus connecting the viewer more directly with the body and with that body’s experience, with its acts.

The central figure crouches in front of a decaying wall, her hands outstretched, her naked back covered by a piece of fallen wallpaper. This Venus is not a perfect blonde, she is a disheveled brunette; she has emerged not from the sea but from a moldy old house situated not on the Mediterranean but in New England, and her shell is manmade, not natural. The Italy that inspired Botticelli also gave Francesca her name; she spent time there as a child and again a year after this photograph was taken, during a junior year abroad, where it became another setting for her work. Botticelli’s Renaissance Italy serves as a recognizable cultural geography that Woodman overwrites with her vision of Venus as a figure defined by culture rather than nature; she portrays Venus as a modern artist whose birth is self-generated even if, like Botticelli’s modest beauty, she remains self-protective.

Despite the decay, the architectural features that anchor the image—the baseboard, an old telephone outlet and the edge of a window frame—suggest that this neglected house is surviving and remains capable of containing this human creature, head bent, hair tousled, and whose shadow shows she is real, even if the setting lends her a mythological air. If we read this image as we would a map, the location we attempt to reach lies in the indentation between the figure’s shoulder blades—at the site of a circular tear in the wallpaper shell—which draws the eye upwards to the head, a rhyming dark space but one that is full, sharing only with the torn paper the implication of receptivity. Then, from the lowered head the eye travels upwards to the hands, spread outwards, supporting the body against the stained wall. The wall’s ridges, gouges made to hold wallpaper glue, rhyme with the fingers because, like this body within its shell, they were intended to remain hidden, as underpinnings holding up the façade.

The companion piece to this third Providence image comes from a different series, Space2. It dates from 1977 yet seems to belong together with the third captioned Providence photograph from 1976 because it appears to have been shot in the same room and again features a nude woman and wallpaper. This time, however, the woman stands against the wall facing the viewer and holds the wallpaper over her lower and upper torso in place of Botticelli’s Venus’s hand and hair. Two windows symmetrically flank the figure; uneven floorboards lead the eye to her bare feet; the baseboard buttresses the crumbling wall. Even though the wallpaper appears to be attached to the wall at first, it becomes evident upon closer examination that it just looks that way, it just seems that the woman is emerging from the wall like a ghostly figure from ancient myths about transformation or from seventeenth-century fairy tales or the eighteenth-century gothic. The house’s decrepit state reminds the viewer of gothic precedents in which the supernatural was normalized and houses seemed alive; at the same time this house has been stripped of the patriarchal menace sometimes linked to the gothic—the body that blends into and emerges from it at will is far from its prisoner-victim.25 The viewer is invited to consider the inner geography that this house-body reveals: what is it like to inhabit such a body, capable of emerging fully formed into this ruin? These questions stem from the narrative function of her images in series, which tell stories: of young girls at play in ramshackle houses, for example, laying claim to spaces from which, paradoxically, all signs of domesticity have vanished, leaving them free.

Read the rest of the essay HERE

(All rights reserved. Text © Katharine Conley. Images @ the Estate of Francesca Woodman.)