Blushes #28, 2000

“Ever since I started printing in 1990, I’ve been collecting things that went wrong in the darkroom.”

By Nathan Kernan, from “What They Are” originally published in Art On Paper, May-Jun 2001

Photographer Wolfgang Tillmans was born in 1968, in Remscheid, Germany, a small town not far from Dusseldorf. He moved to Hamburg after high school to do community service in lieu of being drafted into the army); and there he continued to make the Xerox art that he had begun to produce during his last year in school. He had his first show of this work at Cafe Gnosa in Hamburg in 1988. Needing pictures to use in the Xeroxes, he bought a camera and soon became more interested in his original photographs than in their “degradation” as photocopies. Tillmans first made a name for himself taking pictures of club kids, which he published in i-D and other magazines, but after deciding he was “too young to be a professional photographer;” he moved to England and enrolled in a two year photography program at the Brighton and Poole College of Art. Since 1992 he has lived mostly in London. In such books as For When I’m Weak I’m Strong (1996) and Burg (199 ), and in gallery and museum installations, he combines still-lifes, portraits, landscapes, scenes of communal celebration, and , recently abstractions, with a seeming casualness that is anything but casual. Tillmans was the winner of the 2000 Turner Prize and a large retrospective of his work will open at Hamberg’s Deichtorhallen this fall later traveling to the Castello di Rivoli in Turin. At the time of our conversation there was a show of his new work at Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York. – NK

Nathan Kernan: In your current show you include a lot of cameraless abstraction, in addition to, or sometimes as interventions upon, “straight” photographs. Can you tell me about how you started to make these abstractions?

Wolfgang Tillmans: Ever since I started printing in 1990, I’ve been collecting things that went wrong in the darkroom. I’ve always taken great pleasure in interesting accidents, and as I saw them happening I would then use that as a chance to experiment, shaping the accidental. But I never showed any until I was asked by Parkett in ’98 to do an edition, and I gave them 60 of those darkroom accidents. I don’t really like gratuitous editioning – all my work is editioned already – so usually when I do editions I try to play with the actual concept of multiples and uniqueness. So for Parkett, everybody got a completely unique picture.

But, in a way, abstraction is something that I have always done. I don’t know if I mentioned those black-and-white photocopies to you, which I was doing from ’87 till ’89, using found photographs, newspaper photographs, or my own holiday photography. I was enlarging them on a digital photocopier by Canon, which had this huge enlargement facility of 400 percent, and I would zoom into the image, and then enlarge that enlargement 400 percent, then that one, and so even after the first step the picture would be very grainy-pixilated and after three steps what was left was just a pure graphic design. And so this exploration of the image surface, of the very nature of what constitutes an image, has always been of great fascination to me, how in a way it’s all just a likeness and never the real thing, but also how something you mark on paper is transformed into something that you look at and see something else in. It’s the same today with the Blushes in the current show, for example, which are almost on the border between something and nothing; and when does “something” become “something… else”? So in a way I started being interested in photography through deconstructing or destroying photography.

NK: The new pictures of riders in the London Underground are also very abstract, very unspecific and formal.

WT: And that’s the interesting role that the abstract pictures play: they activate shapes in the other pictures. So the fact that they are abstract isn’t really that important. Because all the different abstract pictures look like they are pictures of something. And that’s important to me, that they are not necessarily just another exercise in abstraction, but also somehow in dialogue with photography and the illusion, or the assumption, that a photograph must be of something. And of course, every single one is an imprint and a trace of light that has happened to the paper.

NK: How do you make those Blush marks, those wire-thin lines and tiny particles?

“The initial question everybody asks when confronted with a photograph is who is it, when was it made, how is it made, and when you’re confronted with a painting you don’t ask that.”

WT: They are all done with different light sources, like flashlights, and the Super Colliders with a laser, and it’s quite an involved process which I don’t really want to go into because, again, I want them to be what they are, and not just how they’re made. The initial question everybody asks when confronted with a photograph is who is it, when was it made, how is it made, and when you’re confronted with a painting you don’t ask that. I mean, why can’t it be enough to look at the object in front of you?

Super Collider #2, 2001

NK: Yet to me the Blushes are very close to gestural abstract painting, which is not about the object only, but also about the gesture and the act of making it. Do you feel that plays a part in your work too?

WT: It is an act, I mean it is a time-based process which I have to get into. I don’t want to over romanticize it, either, but it is kind of an intuitive process, and I need to kind of bond with the material that I’m using, and then over time I develop a sense of, for example, how to filter to get the color I want, or time the exposure exactly, or make a movement quick enough so that the paper doesn’t get too dark-and all that is, of course, very much like what a painter does. So it is a very physical thing; and I love this sheet of paper itself, this lush, crisp thing. A piece of photographic paper has its own elegance, how it bows when you have it hang ing in one hand or in two, and manipulate it, expose it to light – I guess it is quite a gestural thing. And now l have set up a new darkroom where I can be more involved with that.

“I don’t want to mimic painting, and I think it’s actually crucial that they are photographs.”

NK: “Painting with light.”

WT: Well, you know, it’s an obvious term that comes to mind, but, on the ocher hand, I think it’s been used in the past in an apologetic way, in the past decades, trying to sort of bring photography to some level of perceived higher – well, to painting’s status. But I don’t want to mimic painting, and I think it’s actually crucial that they are pho tographs. In a way, they are not doing anything that photography doesn’t do anyway, because they arc recording light. They’re inherently photographic, and they are not like painting. I mean they are not abusing the photographic process to do something else and so in that way they are as truthful as any photo can be. I think that it goes back to just letting them be what they are in front of you.

Another thing that is important about them and which ties them into all the rest of my work is the simplicity of how they are done. And even though I don’t want to explain the exact technical process, the fact is that they are made very simply, and, as with all my other pictures, I am interested in how I can transform something simple, or even something complicated into something else.

NK: After you started taking pictures in clubs, you took pictures with your friends that were not spontaneous, but were collaborations with the subjects.

WT: Yes, in ’89, or shortly after, I started to use people as actors of ideas or actors of their own ideas, like a kind of collaboration, or a way for me to see what I would like to see. I soon realized that photography is a good way to see situations with your own eyes that you would like to see, like scenes of togetherness, for example, and you can’t – it’s kind of strange to ask people. “Could you hold each other because I want to see what it looks like?” But with a camera everybody instantly agrees, they understand that that is a good enough reason. And this is actually one thing that I really enjoy about photography and have used ever since I noticed it is possible: a camera gives a good reason to be allowed to look at things.

NK: Were the Lutz & Alex photographs structured as fashion in some way? They were done for i-D weren’t they?

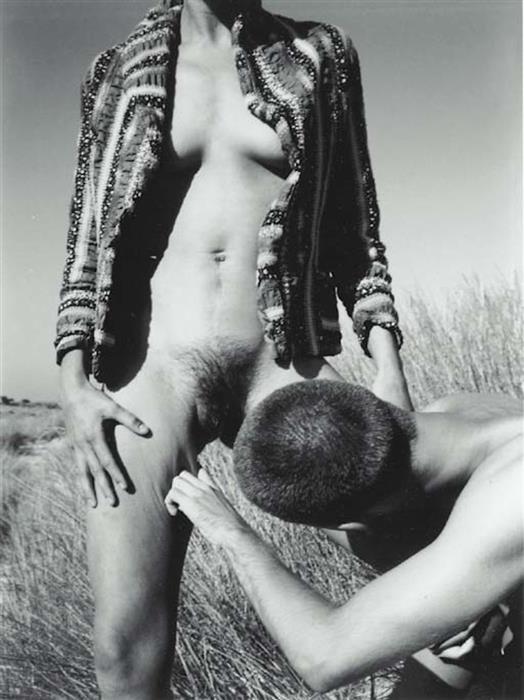

WT: They were in i-D, yes. I realized that the fashion pages were actually the only pages in a magazine where you could think about these things and publish pictures without having to tell a story or be documentary or report something. It’s the only space in a magazine where you can just show pictures for what they are. And they were using a magazine as a reason to enact something I wanted to see. I really wanted to bring my ideas of sexuality into this context of i-D, to represent a man and a woman as partners, rather than the woman as the sexploited one and the man in control. The man is, in a way, as exposed as the woman, since toplessness isn’t equal in the genders, it’s only equal when (as in these pictures) it’s topless for the woman and bottomless for the man. So there were a lot of ideas which I had gathered over the years which in this weekend all crystallized. And so the pretext was, yes, it is a fashion story for i-D,but what was going on there were things that I wanted to do and the clothes idea I had, and so it’s just been my work . Saying it’s fashion but meaning that it’s not really work is wrong; that it said what it did in a fashion context was totally intentional.

NK: I loved it when you said once that you don’t believe in snapshots, because it made me wonder whether maybe we’re all too visually aware to even be able to take a snapshots anymore.

WT The big misunderstanding of the ’90s was people thinking it’s all about “anything goes,” people snapping snapshots. The notion that you can take anything has been around a long time; in terms of art it’s not a very interesting idea. But, on the other hand, I am always interested in how I can make photography do for me what I want it to by any means possible, including carrying a small camera around with me at times. So there are moments when l just try and see, well, can I take a picture of this at two o’clock in the morning somewhere? It is possible that a great picture can come from that.

NK: AA Breakfast.

WT Yes, for example. Exactly in that moment it was the appropriate camera. No other camera would have given me that picture. In a way, that is a good example of when a very of-the-moment, in-the-moment readiness of the camera is the only way for the camera to be. But that’s not my dogma. That it does happen now, here, this second, doesn’t make it any better or any more authentic. I think that’s what I’ve wanted to say. I don’t want people to assume that my pictures are any more or less real than anyone else’s – they are all real because they all happened in front of the camera. But then at the same time they are all constructions, they are not real, they are photographs, and they are my way of making the camera do what I want it to do, or trying to. And it’s always more like an attempt. And it’s a lifelong process to get better at it.

“They are my way of making the camera do what I want it to do, or trying to.”

NK: Some of your new works, such as the inkjet prints of the Conquistador series, are editioned re-photographs from one-of-a-kind originals. Is that how you edition your non-abstract work as well?

WT: No. Normally I have a negative and I print from that. But conceptually the uniqueness of the abstract ones is not important to me, and so I only keep them unique when it’s technically necessary, that is, when they can’t be re-photographed in a good enough quality.

NK Would that apply to the Blushes?

WT Yes. To be exact, they stay unique because the shifts in color are so faint that I can’t really photograph that again. But in general, whenever I can, I edition them because I do believe in that image, and I want to use it at least a few times, rather than it just being done once and then gone. But because I either do all the prints myself, or they are done in my studio, l can only do a small number, and that is why my editions are always small, either one or three or ten.

NK: What about the inkjet prints? I remember you referred to them as “manifestations” of the image, and that if one deteriorated out in the world ten years from now that you would replace it, is that right? You seemed to acknowledge their inherent impermanence.

Lutz & Alex, 1992

WT: Yes, with those it is actually part of the work. I know that they will deteriorate, but there is nothing I can do about it, and the qualities that I get from the inkjet are definitely worth it for me since they offer something that no other technique can offer. And, to be honest, I think they are probably the most archival conceptually, because you can just store the original master print that was used to print the inkjet from, in whatever safe, dark, cool conditions you need to, and then you can reprint the picture as many rimes as is necessary – as long as you destroy the previous one – and also given that inkjet printing will always become better, it’s actually a very safe medium. In a way this fragility of the inkjet is kind of an image of paradox – this sort of fragile and perishable quality which is also its beauty.

I guess I could have an easier life if I didn’t care so much about all those different manifestations of an image, you know, didn’t care about making the prints myself or in my studio, but somehow that is my work also, and the time spent dealing with a print is also time spent with the work. And I do understand my work better through that. I can judge it better, because if I have spent many hours making it I do have a closer eye on it than if it just arrived from the lab at the gallery ready-mounted, ready-framed.

NK: You mentioned that you would be going back to – not that you ever left – taking more portraits of people again, like the portrait Cliff in this show.

WT: Yes, the whole last year I’ve been taking more portraits again and it’s something I guess I won’t ever really tire of – sometimes I don’t feel l have anything to add to that, and then suddenly after a year or two I find there’s a renewed, a refreshed interest in people, because in a way being tired of people as a whole would be a dangerous thing to happen, for me. The act of taking a portrait is just such a fundamental human act – it’s a fundamental artistic act – and the process of it is a very direct human exchange, and that is what I find interesting about it. The dynamics of it never change, no matter how successful you are or how successful the sitter is or how famous anybody involved is, the actual dynamics of vulnerability and exposure and embarrassment and honesty do not change, ever. And so I found that portraiture is a good leveling instrument for me. It always just sends me back to square one. I’m not saying it’s something you can’t get better at: of course, it develops. But it requires me as a person to be sort of intact and fluid.

[nggallery id=593]

ASX CHANNEL: WOLFGANG TILLMANS

(All rights reserved. Text @ Nathan Kernan, Images @ Wolfgang Tillmans)