It was not so very long ago that Detroit was among the most august of American cities.

By Vladimir Gintoff, ASX, September 2013

It was not so very long ago that Detroit was among the most august of American cities. Once the home of two million people and the country’s fourth largest metropolis, Detroit’s population has shrunk to 700,000 and given rise to 80,000 abandoned structures. The awe and melancholy beauty of the graying and hobbled industrial center has captivated photographers, and inspired projects like Andrew Moore’s Detroit Disassembled, Yves Marchand & Romain Meffre’s The Ruins of Detroit, and Julia Reyes Taubman’s Detroit: 138 Square Miles. Arianna Arcara and Luca Santese, both Italian photographers, also went to the Motor City to explore these blighted American landscapes, instead they found photographs and took a different, and remarkable approach.

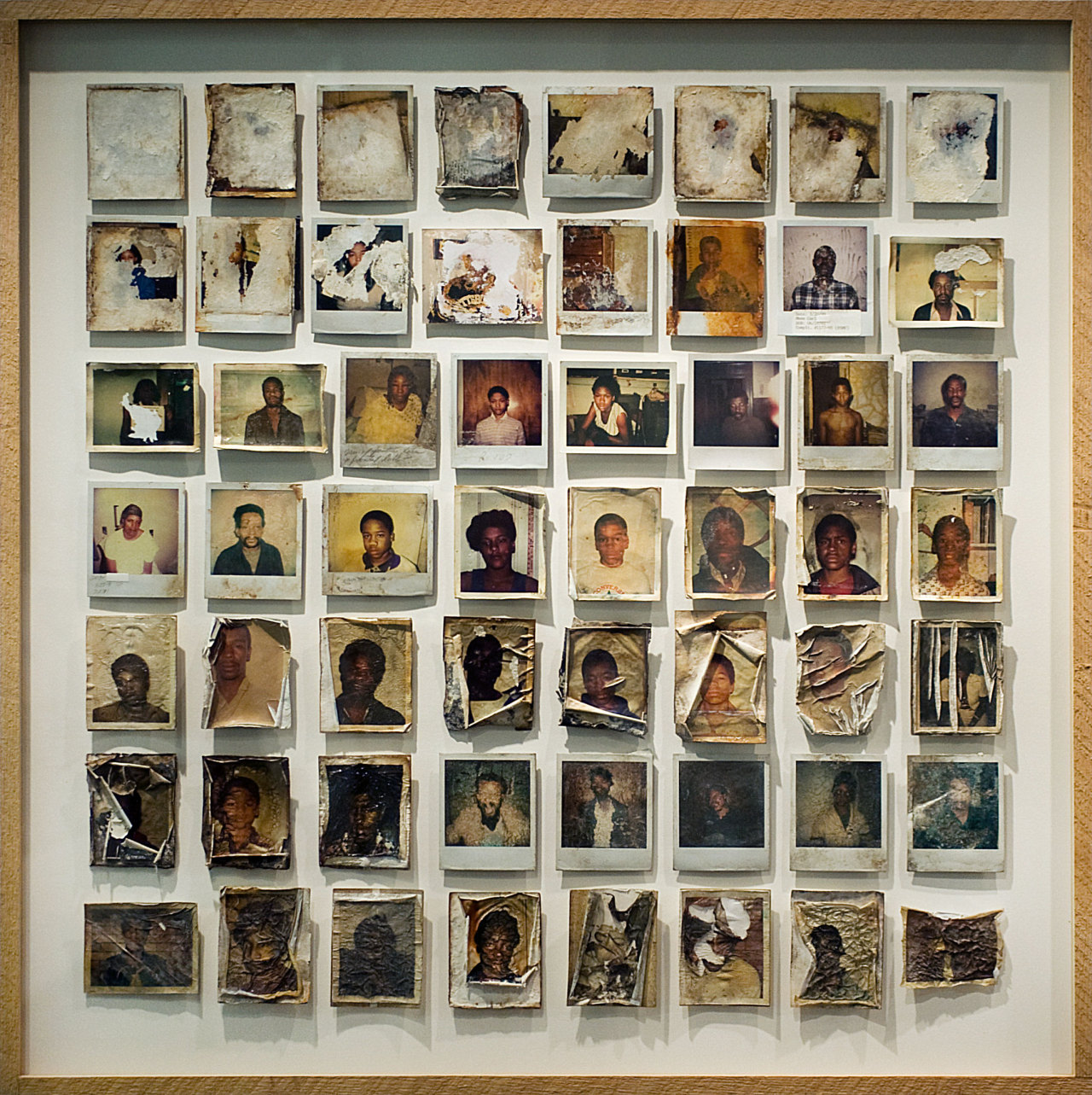

The result, Found Photos in Detroit, is an oversized hardcover with brown paper binding and no dust jacket. A small embossed area on the cover displays the title on a white adhesive label. It makes the book look somewhat like a filing-cabinet drawer, which is familiar and appropriate for an archive of images. Arcara and Santese’s compilation displays a selection of their favorite and most compelling discoveries. The photographs are printed to size on pristine white pages, in stark contrast to stains, ripples, cracks, and tears they have acquired through neglect. Made between the 1960s and 1990s and found in the vacant buildings themselves, the photographs are a natural documentation of Detroit’s racial inequality, anemic growth, ballooning crime, and crumbling infrastructure.

These moments of a ghostly yet normal life are juxtaposed with records of crimes and other misfortunes. Like location scouting for the crime show The First 48, a house is shown from various angles.

Detroit has had a black majority since the early 1980s, and the photographs attest to these demographics. The characters who populate Found Photos in Detroit appear to have been from all walks of life and a variety of circumstances: men standing in front of new cars, Sears portraits, group portraits, choir singers, men lined up in suits, Halloween costumes, families at the dinner tables, a shirtless boy flexing his arms to presumably be showing the marks of physical abuse, a women at her office cubicle, people sitting by the pool, etcetera. The first section of the book is devoted to grids of polaroids and rectangular color photographs. All faces and some shoulders, head-on, without explanation, and largely all are melting down, quite literally.

Like location scouting for the crime show The First 48, a house is shown from various angles.

These moments of a ghostly yet normal life are juxtaposed with records of crimes and other misfortunes. Like location scouting for the crime show The First 48, a house is shown from various angles. There are harsh, flash-lit photographs of the outside, windows, porches, and bricks covered in ivy, mixed with images of the abandoned interior, blood spattered on pink linoleum, a dark and waxy door made suspect by a broken lock and splintered frame, and several red shotgun cases, at the foot of stairs carpeted in a rich emerald shag. In other narratives there are small handguns, blood spattered sheets, a corpse seen through french doors, and another body outside the cab of a pickup truck, idling, the roadside covered with snow. The photographs appear as police evidence later left for Arcara and Santese to reuse after the police are long gone, evaporated by shrinking budgets and empty coffers.

Instead there is loss on a human scale and a price paid in wreckage, decay and human blood.

There are also several letters, both typed and hand-written, and filled with profanity. These are the book’s only words and do little to contextualize the pictures with which they are paired, yet they offer jarring emotional and violent subtext. We must reach our own conclusions about these photographs and the city they were found in yet Arcara and Santese lead us down a path, one that could not have been created with their own photographs. While dates can be approximated, it is difficult to fit Detroit’s troubles into a larger American narrative. It’s trajectory is one where the automobile, that which brought Detroit to the pinnacle of American opulence, is unavoidably tied to the city’s misfortune. For it was the car and prosperity of the 1950s that birthed the idea of suburban life and the US Highway System. As the icon of American Freedom, the automobile enabled people to leave the toil and grit of crumbling urban centers for a future of manicured lawns and pool clubs.

Arcara and Santese provide an unexpected portrait of Detroit, eschewing the obvious for something more cerebral. The majestic decay of lavish theaters, incomprehensibly large car plants, and skyscrapers of former luxury are not to be found here. Instead there is loss on a human scale and a price paid in wreckage, decay and human blood. The beauty of this collection is in the physical degradation of images, which act as companions to and reflections of the city’s precipitous decline, and the assaults on the quality of life possible in such an environment. It seems that Arcara and Santese realized that their own photographs, no matter how strong, could never equal the beauty and power in these remnants of lives lived and impacted by a city that is imploding. Often working like a primer or an incomplete narrative, we are allowed to infer and generate our own interpretations and reflections through the stories of these nameless figures. Now we are left to wait, watch, act or wonder if the recent signs of a turnaround in the city will be the start of a new beginning or if the can will only getting kicked farther down the road and left to rust. Time will tell.

Found Photos in Detroit

Edition of 1000

Collected, edited and designed by Arianna Arcara & Luca Santese

Printed in Italy by Fontegrafica

Hardbound, 16.5 x 11.7 in / 42 x 29,7 cm

80 pages, 167 photos, color offset

Vladimir Gintoff graduated from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts in 2012 with degrees in Photography and Art History. He writes for ASX and works as a gallery assistant in New York.

(All rights reserved. Text @ ASX and Vladimir Gintoff, Images @ Arianna Arcara & Luca Santese)