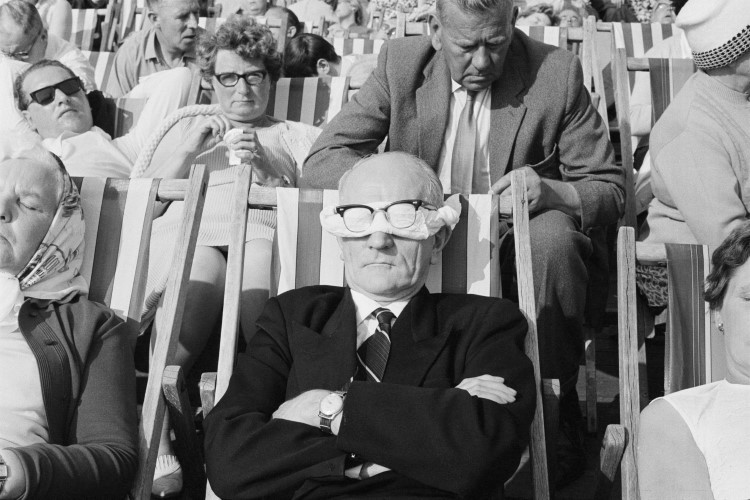

Blackpool, Lancashire,1968

‘I want my pictures to bite like the images in Bunuel’s films which disturb you while making you think. I want them to have poignancy and sharpness but with humour on top.’ – Tony Ray-Jones

By Ainslie Ellis, originally published as the introduction in A Day Off, and English Journal, 1974.

In San Francisco on 18 February 1972 Tony Ray-Jones was told that he had an acute and rare form of leukaemia. He died in London at the Royal Marsden Hospital less than a month later. He was thirty years old. The pictures that he took, and what he had to say about photography, these are of singular importance.

It is difficult to think of any other British photographer but Tony Ray-Jones whose pictures have that rare blend of humour and sadness which is born of both compassion and irony. This is something that springs from the depths of character and it is something that cannot be copied or faked. The imitation, the phoney baloney version of the mixture, as Tony would say, is a blend of sentiment and sarcasm, and is totally alien to his work and to his nature. To find the key to Tony Ray-Jones’s photography one must look first to the cinema, to the films which he loved. A friend of his, a student of the same period at the London College of Printing, David Burch says:

‘I have seen him quoted as being influenced by Vigo, Bunuel and Fellini but it should also be remembered that he loved the films of the Marx Brothers and Jacques Tati. I went with him to see Mon Oncle and he was in hysterics in some parts of it. The scene on board ship in A Night at the Opera where the small cabin is bursting at the seams with people and Groucho invites yet another character to come on in and walk around was one of his favourite sequences. Chaplin, too, interested him very much. When he was sharing a flat near Baker Street he had a very erratic projector but used to run a Chaplin film just to point out the composition of the shots.’

Anna, his wife, says that of all the many films which he loved none compared in his mind with Jean Vigo’s ‘L’Atalante’. This film about life on a barge, the marriage of the skipper to his girl, with Michel Simon’s incomparable portrait of the monstrous old seaman in his crabbed cabin, is shot through and through with bucolic humour and the poignant irony that Tony was to make his own with other subjects and in still photography.

There is, too, a surreal quality about the humour that he loved. For instance Buster Keaton, another of his heroes, has a sequence which particularly amused him. Keaton goes into a bar, takes off his jacket, picks up a piece of chalk, draws a coat hook, and hangs his coat up on it. Surrealism creeps into many of his best photographs. Now Surrealism is basically a curious extension of the ordinary, the bump of surprise that jolts us awake. He had visited the Magritte exhibition at the Tate Gallery but took the trouble to enquire carefully what one of the attendants thought about it. He found out that the things he said were, in fact, deliciously obscure and in a curious way highlighted Magritte’s pictures. Writing in Creative Camera in October 1968 he makes an important statement about his attitude to his photographs of the English, a recurring theme:

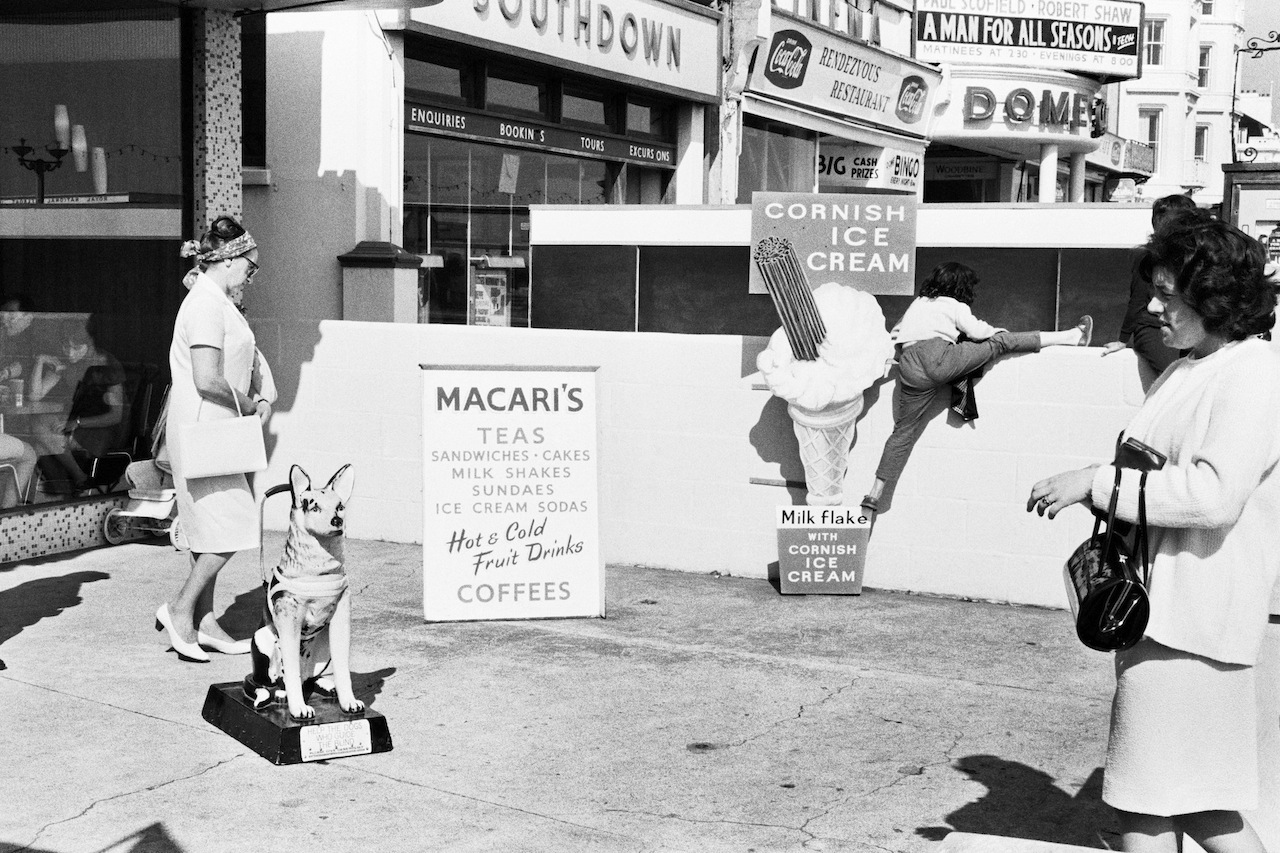

‘My aim is to communicate something of the spirit and the mentality of the English, their habits and their way of life, the ironies that exist in the way they do things, partly through tradition and daily anachronisms in an honest and descriptive manner, the visual aspect being directed by the content. For me there is something very special and rather humorous about the “English way of life” and I wish to record it from my particular point of view before it becomes more Americanized. We are at an important stage in our history, having in a sense just been reduced to an island or defrocked and, as De Gaulle remarked, left naked. Nudity is perhaps more revealing of personality than a heavily clothed figure.’

Tony sensed the natural eccentricity which has always been a quality of life in this island. He was quality of genuine interest, as opposed to crude curiosity, that is the key to positive contact and relationship. The series on English Eccentrics that he did for the Sunday Times was one of his best sets of pictures for a periodical.

He worried tremendously about layout, the final use to which a photographer’s pictures will be put. This sprang in part from his initial training as a designer at the London College of Printing, his time as a design scholar at Yale, but most of all from his contact with Alexei Brodovitch. Tony studied with Alexei Brodovitch, and with Richard Avedon, at Design Laboratory, New York ’62-’63. He was subsequently appointed Associate Art Director to Brodovitch on Sky magazine in 1964. Tony had an immense affection and regard for Brodovitch whose views on layout, on the study of contact sheets, and on the qualities of a good photograph, he followed and believed. Some of these views were set down by Brodovitch in an article in Photography in 1964.

‘The journalistic photographer must be his own picture editor and art editor. In a commercial job the art director and picture editor should never be a substitute for the photographer’s thinking. When he looks at the ground glass, he should see not only the picture, but four or eight pages. There are two phases in making a picture. The first takes place when the photo is actually shot. The second seeing comes in examining the contacts. It is important to be able to express the pictures which express your viewpoint. It is also important to recognize the accidents which often result in good pictures. ‘What is a good photograph?” I cannot say. A photograph is tied to the time. What is good today may be a cliché tomorrow. The problem of the photographer is to discover his own language, a visual ABC. The picture represents the feelings and the point of view of the intelligence behind the camera. The disease of our age is boredom and a good photographer must combat it. The way to do this is by invention – by surprise.’

From A Day Off

Peter Turner of Creative Camera remembers how Tony looked with admiration at a copy of Minotaure, the Surrealist art magazine of the ‘thirties. While he particularly admired the layout, it was not only that, it was the atmosphere – the atmosphere to be found in the photographs of Brassai and Kertesz – that somehow expressed the essence of the time. ‘This is what we’ve got to get going now’ was his opinion. But it is also the reason that his pictures will last. For they, too, magically preserve the essence of his own time.

Tony Ray-Jones, born in Wokey Wells, Somerset, 7 June 1941, was christened Holroyd Anthony Ray-Jones. Holroyd is a family name and was taken from his godfather and uncle but Tony preferred always to use his shortened second name. His father. a distinguished painter and etcher, died when Tony was eight months old. His mother – incidentally she is an intrepid traveller in later life who thinks nothing of going by bus to India, or taking the Trans-Siberian railway to Peking, or voyaging the length of the Nile as a venture – found herself with three boys to bring up on the vestiges of an artist’s income. She says that she could not have done it without the help of the Artists’ Orphan Fund. This is a fund administered by the Artists’ General Benevolent Institute. The name sounds somewhat forbidding but she says that, on the contrary, she found them sympathetic, interested and understanding and is still full of praise for the help they gave her.

His father, Raymond Ray-Jones, was a Lancastrian who had gained a Royal Exhibition to the Royal College of Art and went later to the Academie Julian in Paris. A self-portrait done as an etching in Paris in 1911 is potent and revealing. It has the finesse and force of the best kind of portrait and, one is tempted to add, of the best kind of photograph as well. Colnaghi, who then dominated the market for etchings, only allowed 50 copies to be·made before the plate was scored through. Paintings and prints of his are held by the Print Room of the British Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum and Trinity College, Cambridge. His paintings of France, notably of Provence, are full of acutely observed detail, ambience and warmth. In an entirely different medium and in another mode Tony exhibited precisely the same three qualities in his photographs.

A radical streak later developed which made him want to resist all forms of injustice.

Compassion and humour were features of Tony’s character all through his short life. But a radical streak later developed which made him want to resist all forms of injustice. He was. in fact. a born Socialist – in the true sense of that over-fingered word. Anna, who first met him when he was twenty-five said that, at that time, he was largely apolitical but was becoming increasingly aware of political issues. While he moved increasingly to the left in his ideas. becoming more and more radical during the last five years, he could always appreciate that the anarchy of the Marx Brothers was in its own way as potent and valuable as the teachings of Karl Marx. Above all, Tony was for people, for the victimized, for the oppressed, for the underdog whoever he was and wherever he might be found. Ernest Cole’s The House of Bondage, for instance, was a book that deeply impressed him.

He went to school at Christ’s Hospital. According to his friend David Burch something in his background drove him to be very nervous about failing and not making the grade.

‘I gather that at school he felt himself something of a misfit. He would argue fluently with lecturers about his work and at one stage he was so depressed about it that his mother had to enquire for him if his progress was worthwhile. The reply was that his work was very good and this seemed to give him confidence.’

David Burch has this to say about their time together at the Lonqon College of Printing where he first met Tony in 1957.

‘The School was then situated at Back Hill, Clerkenwell, opposite the Old Holborn Tobacco Factory. During the lunch hours we would sometimes wander down Leather Lane and watch the stall-holders and listen to their sales talk. The training at the School was split into two within the Design Department and at a certain stage one could opt to train as a Typographic Designer or as a Commercial Designer. Tony took the Commercial course.

‘In the second year of the course Photography was part of the syllabus and this was geared particularly to Advertising Design and Photography. The technical processes of photography were taught and this is where Tony began to learn the basic techniques of the craft. ‘

‘At this time I don’t believe he owned a good camera and the amount of time spent in the photographic section was limited to about one day per week plus an evening class at the best.’Tony bought a camera, a Rolleicord I think, which caused him some concern. Something was at fault in its manufacture with the result that things that registered in focus on the viewfinder did not correspond to the focus of the lens. All the photographs were fractionally out of focus. I can remember him fuming in the darkroom, examining the enlarger and his developing procedures and saying how awful his work was. Finally he had the camera properly tested and then returned it to the makers with a marvellous letter. I believe the camera was corrected or replaced.’

These remarks all point to a feature of Tony’s work which it is important to bring out. He was a craftsman before all else. He worried constantly whether there was something in the chain of processes between the subject and the final print which might not be improved. He consulted the Editor of The British Journal of Photography, not only on the best lens he could use for a particular problem but on the possibilities, which haunted him, of making a master print from which, he hoped, exact and perfect copies might be made for future use. The technical drawbacks of this idea were explained to him. The perfect print, the best that could be achieved from his negative, was just one side. but a revealing one, of his craftsman’s passion for the ultimate in his work.

What were the earliest influences in his photography? Bill Brandt’s brother was one of the lecturers at LCP at that time and Tony was particularly impressed by Bill Brandt’s early photography of the English scene. Originals of these were on view at the college and he went to see Brandt and show him some prints. When he was asked what happened he said: ‘They made Brandt laugh a little, they amused him and he said to get in closer.’

Bill Brandt wrote recently.

‘Tony Ray-Jones showed me some of his photographs about ten years ago. This must have been right at the beginning of his career, but he had already then a very pronounced style of his own. He didn’t seem to be influenced by other photographers, which at his age, was quite remarkable. Unfortunately I did not see any of his later work, but I think his death, at such an early age, is a terrible loss to photography.’

He won a scholarship to Yale University for graduate work in design. He studied at Yale in 1961-62 before working with Brodovitch up till 1964. He then freelanced in America for the next two years. His contract with America was all-important. America turned him on. And in a particular way it matured his vision, stimulated and infuriated him, immersing him in a love-hate relationship that developed him as a photographer and as a person.

Alen MacWeeney, an extremely successful American fashion photographer says:

‘Tony loved America … he thrived on the bizarre and quixotic moods and fancies of contemporary life in New York. His immersion in the current scene and his involvement with it as subject matter was very stimulating to him. The grosser the sight the more irony per square inch, the better he liked it. Sometimes I accompanied him to his favourite happenings/ a mass frolic involving chicken carcasses for example. After a short time I would feel confounded, exhausted and depressed by what confronted me. But not Tony. He would be bobbing about full of enthusiasm and ready to dig in deeper.’

Anna Ray-Jones says that the reason he could keep on like this was that he was far from appalled because there was sympathy present. The subject was not merely an object to him: he felt a relationship which he respected. MacWeeney says of Tony in these early years in America.

‘His tastes vacillated continually. For example, when we first met and I expressed enthusiasm for Robert Frank’s pictures and Brandt’s, Tony couldn’t understand my feelings. Later, of course, he made these feelings his own.’

The fact that ‘his tastes vacillated continually’ is no bad thing.

This statement, certainly about Bill Brandt’s work, conflicts with those of people who knew him before he went to America. The fact that ‘his tastes vacillated continually’ is no bad thing. A young photographer should be open to fresh influences, should be capable of revaluations, reassessments. That he was open to criticism of his own work at every stage in its development is not in doubt. However one or two people found his criticism of their work on the harsh side, he did not mince his words and was inclined to be unsparing. John Benton-Harris, an American freelance who since Tony’s death has processed and enlarged much of the recent work, put it this way.

‘You might say he became a Joan of Arc purist in criticism. It wasn’t always necessary to call an ace an ace, a spade a spade: He could bring my pictures and myself down a little too hard. Being honest can hurt.’

He could never understand lack of enthusiasm, in students for example. He drove himself as if he sensed there was little time to lose. Benton-Harris says he was an amazingly good hustler, and other photographers have remarked that he had a knack for reminding them what it was all about. He had a charismatic power to instill enthusiasm and he could have become a remarkably good teacher. The fierce criticism, the radical element in him, was balanced by a natural unaffected charm, a ripe sense of humour, real warmth. This is how he struck Jacques Lartigue, a photographer for whom he had the greatest affection and regard. Lartigue writes:

‘At Opio, in 1970, I had the surprise one day of a charming visit, that of Tony Ray-Jones. Intelligent, young, free “et fantaisiste”.(Translator’s note: The nearest one can get to this delightful word in English is “expressing gently humorous tolerance, or whimsical”), he travelled in a dormobile. Without knowing him I sensed at once that he must have talent.)

Several months later, in a gallery at that time directed by my friend Pierre de Fenoyl, I was able to see his first exhibition in Paris and I am always delighted when I meet real talent. His was like himself: young, intelligent, free and whimsical with, in addition, a very sound technique and a vision of fire that was full of humour, truth and a sense of poetry in certain subjects. I am very certain then that in spite of his presence for too short a time on earth, his work will leave behind a very profound memory.’

Tony also thought highly of the work of Paul Strand and, for instance, particularly liked the whole presentation of his Mexican Portfolio.

Paul Strand first saw Ray-Jones’s work in Album 3 (Ed. Note: Bill Jay’s short-lived journal).

‘In its all too brief existence Album brought forward memorable works of both known photographers, past and present and not less importantly gave its pages as well to photography by new developing artists. ‘Among the latter, I found the photographs of Tony Ray-Jones very outstanding. In them I find that rather rare concurrence when an artist clearly attaining mastery of his medium, also develops a remarkable way of looking at the life around him, with warmth and understanding. His vision of people as they live in the neighbouring worlds of reality, is comprehensive and complex. Such photographs as “Durham”, “Broadstairs” and “Ramsgate” among others, show a remarkable formal organization, the consistent ability of the photographer to seize images constantly in change and movement, in which however everything he includes in the picture is and unified as a true work of art must be. To my mind “Ramsgate” is a masterpiece of this very inclusive seeing in which the photographed reality, never sighted, is fully alive in every part and as a complete whole.

A young man who had advanced so far along the difficult road of so significant a marriage of form and content is rare today in any medium. The tragic death of Tony Ray-Jones who was working in the great tradition which began with D. 0. Hill, is a real loss to the art of photography in Great Britain and to people everywhere.’

The pictures that he made on his first visit to America he regarded later as merely isolated sketches. He came back to Britain ‘with a foreigner’s outlook, as well as that of a native’. He now felt that apart from Bill Brandt, England was unexplored from a non-commercial point of view. He turned with a fresh eye to two related sides of English life: holidaying at the seaside and old customs and traditions. ‘Both the Seaside and Old Customs present an opportunity for people to gather, to interact with each other and their environment and thereby to reveal something of themselves.’

He documented in an unaffected and straightforward manner the often unconscious humour of the English talent for playing life so seriously in its lighter moments.

What was that something? It had to do with humour and sadness, and with the gentle madness that overtakes the British when they feel they can let their hair down and be their true selves. This oddity, this eccentricity, was capable of being set down by the camera. ‘Photography can be a mirror and reflect life as it is. But I also think it is possible to walk like Alice through the looking-glass, ·observe the puzzles in one’s head and discover another kind of world with the camera.’

He did not really feel ready for his first exhibition, The English Seen, which was put on at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in April 1969, but it contained several of his best pictures. A number of prints included in this show (later seen in Paris and in San Francisco Museum of Art) are held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in an archive at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. He took immense trouble to see that these prints should be to his exact liking. As a printer, too, he was demanding. What he sensed, and what he tried to say about the English character is well expressed by George Orwell in a passage about comic seaside postcards. ‘One can learn a good deal about the spirit of England from the comic coloured postcards that you see in the windows of cheap stationers’ shops. These things are a sort of diary upon which the English people have unconsciously recorded themselves. Their old-fashioned outlook, their graded snobberies, their mixture of bawdiness and hypocrisy, their extreme gentleness, their deeply moral attitude to life are all mirrored there.’ Many of his best photographs seem to be single frames, fluidly and fluently composed, from a film that was running constantly through the gate of his mind. This film was the statement he was burning to make about life. Had he lived he would have turned to film-making even though he is on record as saying, in talking about the film Medium Cool, that the cinema could exhibit an incredible weakness as a means of honest expression and that still photographs could be potent where film fails.

His mother says that when he was sixteen he was quite definite that he would start making films when he was thirty. A Christmas card for 1971 says that he hoped to go to film school but did not know whether it would be possible. He was by then back in America freelancing and also a Visiting Lecturer to the Department of Photography, San Francisco Art Institute.

Anna Ray-Jones confirms that he would have begun to make films. A subject that he would almost certainly have treated was the plight of the American Indian. Through his wife he had become very interested in the Hopi Nation in Arizona. David Monongye, an energetic Hopi of 89, had become a kind of spiritual father to them both. And Tony planned a great deal of photography to expose not only the injustices they have suffered but also the richness of their culture. After hearing of Tony Ray-Jones’s death David Monongye wrote to Anna. ‘Don’t live in your grief … We are not alone in this world. The Great One who moves all things must have need of Tony. He is not dead but has taken off his earthly overcoat.’

In The British Journal of Photography, 28 March 1969, my review of his first exhibition ended with this paragraph. It contains remarks of his which seem important:

‘Comment about his individual pictures seem superfluous. They either have an inner truth and magic that works on you. as it certainly does on me. or they don’t. I find myself thinking of two remarks he made. On composition-“you always hoped you could do without it: but when you do the picture invariably falls to pieces and won’t stand up”. And “my thing is that I’m not particularly interested in ‘beautiful’ photographs”. He is obviously interested in very complex images but however complex they stand up and hold together like a Bruegel painting. He quietly remarked something that is full of significance: “I’m concerned with pushing images to the edge of sanity.” For my part I find they have a strange beauty and a great inherent truth-to-life. I think we are looking at the early work of a great photographer.’ Now that one knows the little time that was left to him one can only marvel at the force and vitality that he pressed into his pictures. Several of these will pass not only into the history and development of photography but will remain as a permanent tribute to someone who said: “I’m not an artist. I don’t like the snob connotation of the word. I’m not specially sensitive and I wouldn’t tolerate the stigma. I would like to be a journalist like George Orwell or as Hogarth was in his medium”.’

If you talk to friends of Tony it is his warmth and his good nature that are remembered quite as much as his radical opinions. This remark of David Burch is somehow typical and ought to be shared. ‘I have had many conversations with Tony but the best memory is of the man who said. “Want to see some snaps, Dave?” opened an unlikely yellow box and produced magic. A generous friend. a great arriver on the doorstep out of nowhere. and devoted to the sad, funny, human race. The compassion shows in his work.’

Tony Ray-Jones’s ashes lie on the slopes of the Luberon in Provence, which he loved, and just above Oppede Le Vieux, the last residence of Alexei Brodovitch, whom he revered. His pictures will continue to speak for themselves for they are a living part of what he wished to accomplish. This was to make a statement. ‘A statement so powerful that it would make people change their ideas and attitudes.’ To make this a reality was his hope, and his aim, and the truth-to-life by which he lived.

The influence of Hopper’s paintings is clear in this image (Boarding House, Newquay, 1968).I originally wrote this Introduction as a brief biography for The British Journal of Photography Annual 1973. At that time we could not use enough of Tony’s photographs to give the impression of his true style which A Day Off now abundantly provides. I am particularly glad that it is sub-titled ‘An English Journal’ for this suggests the particular virtues of Tony Ray-Jones’s photography. These include a pungent and rare Englishness of viewpoint, and an identity with the subject that is wry, ironic, but always affectionate. A little like those old-fashioned English sweets full of curiously strong flavours: paregoric, aniseed, clove, liquorice or that powerful winter lozenge known as the ‘Fisherman’s Friend’. The strong, lingering flavour peculiar to them is pleasant but far from delicate.

‘Journal’, too, is right. He was desperately anxious to note down in his pictures a side of life which he saw and understood but which he knew was undergoing the inevitable and quickening erosion of social change. He documented in an unaffected and straightforward manner the often unconscious humour of the English talent for playing life so seriously in its lighter moments. He caught the fun, the pathos and the irony of England right through the stratification of social differences. His accuracy, his truly comic eye – a comic eye that belongs in a great tradition – and, above all, his ability to reflect with warmth and pungency the true flavour of people: all this A Day Off demonstrates admirably.

Tony Ray-Jones has left us. But A Day Off is full of Tony: his viewpoint, his humour and his warmth. He has left us a photographic testament that is wholly characteristic. Time will, I am certain, merely deepen its relish and enhance its value as a true and graphic portrait of the English social scene.

(All rights reserved. Text © Ainslie Ellis / Thames & Hudson)