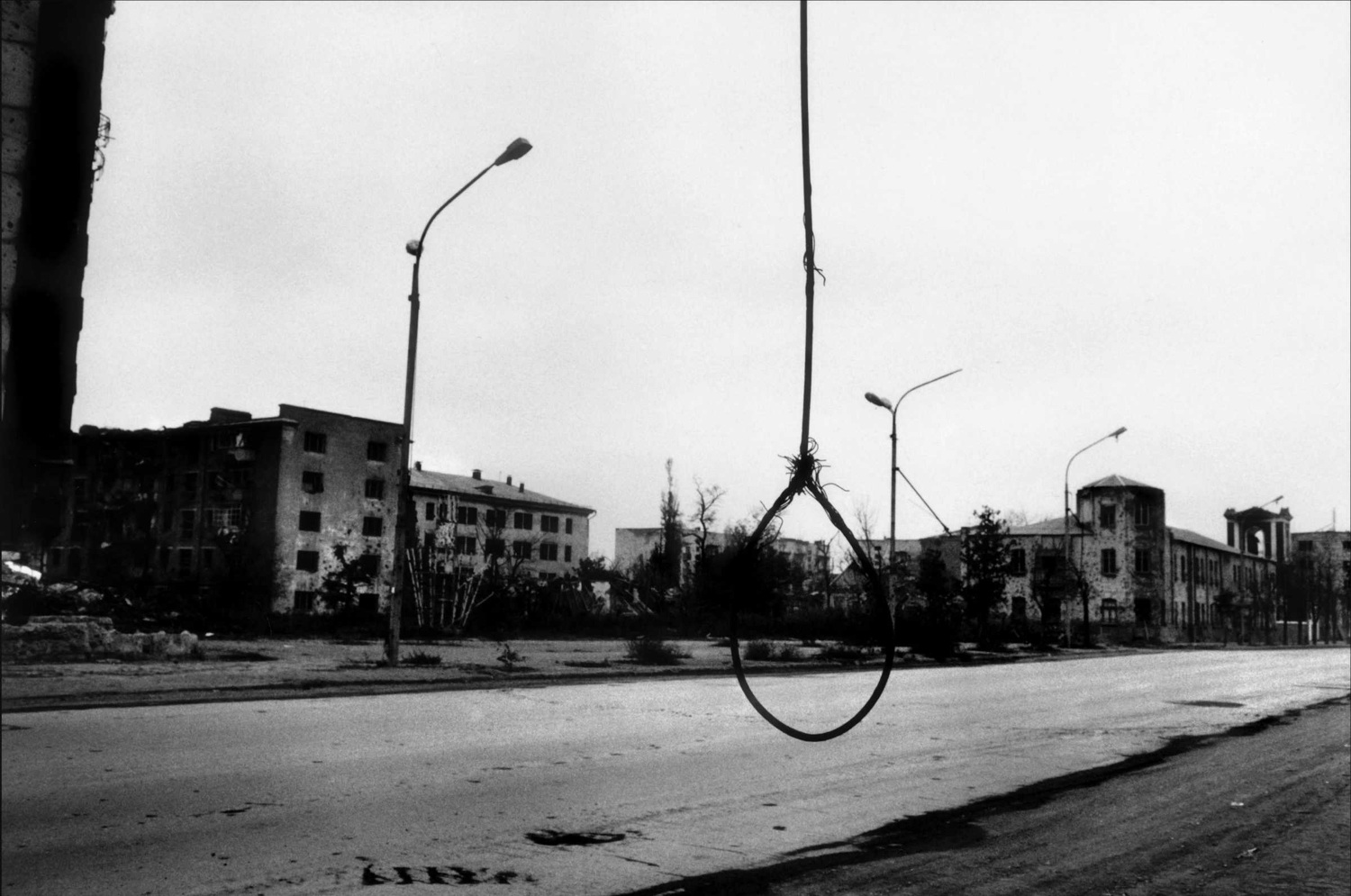

Chechnya, November, 1995 @ Stanley Greene

“We have reached the point where we want to satisfy the bloodlust of the public to the point that we no longer have respect for them. That’s where we’re at.”

Stanley Greene At Visa pour l ‘Image,2006.

Interwieved by Laetitia Martinez , recorded by Cedric Batifoulier, transcripted by David Price . With the kind authorization of oc-tv Toulouse.

LM: How did the work of “Beyond The Wire” get started?

SG: It was a road trip with Sara Daniel, we wanted to cover the route of the coalition forces in to Iraq. We didn’t realise that we were on a voyage into a situation that was going to quickly reveal itself and that the situation in Iraq was not being portrayed properly. The turning point for us was Falloudja. We arrived there when the four contractors were killed. I photographed two of the bodies that had been burnt, dragged through the streets then hung from the bridge.

From that point on it got worse and worse. Right up until the point we drove all the way to the Syrian border, the violence just… it became evident that the country was coming apart. Then we decided to go back a second time because we both kept hearing over and over again that it was like another Vietnam. So I went to Nouvel Observateur and said “Look, they keep saying it’s like Vietnam.” and they replied “Yeah, and what?”, so I said “Well, why don’t we go photograph it like it’s Vietnam?” and they said “Ok, can you do it in digital?” to which I replied “No, no, not in digital, I would like to go with Leicas, shoot film, photograph the American soldiers of the coalition.”

So, I think it took us about two months to get permission to be embedded. And so we were embedded and spent a lot of time bored looking at DVD’s on our computers, then one day a helicopter came to pick us up from Baghdad and took us to Bakuba where we did this report. Again, the situation there all of a sudden just exploded. We were witnessing the violence, the car bombings and the killing of the Iraqi police and Iraqi army.

I purpously left out the the picture of the bodies that I shot because I was more interested in showing the conditions. I wanted to show what was making what we affectionaly called the POI (Pissed Off Iraqis) upset. That was pretty much it. Thats why I call the series “Beyond the Wire”.

LM: Does it mean anything else?

SG: “Beyond the wire” is an expression that the military uses when you go outside the perimeter. It is also a metaphor for going outside the perimeter of insanity and I thought that Falloudja and being embedded in Bakuba, both situations were about going beyond the wire. Beyond the wire, it’s a metaphor for going insane.

Another thing about this work was that, for me, I see it as a religious war. I see it as a religious war because of George Bush and his born-again Christianity and then I see it from the Islamic side with Mokta el Sadr and the Sunnis. Nobody wants to discuss that part of it but for me it really is a religious war. The fanaticism when you listen to Americans speak it’s always about “Us against them”, “We want to change this situation, we want to bring democracy”, which seems to me like a buzzword for “we want to bring them Christianity, we want to bring them our values” but without actually saying it. I’m finding that it appears what America is actually saying about changing the Middle East or bringing democracy is bringing a form of religious consciousness.

Some bodies of people on the ground after an explosion at Cana.

Tyre, Lebanon, August, 2006

Courtesy of Stanley Greene, Black Passport

Abdul Kadhir, is twenty years old and a witness: “They hanged the bodies to a bridge and then launched into the crowd and two more bodies burned. The people gathered around as if it was a barbecue”

Fallujah, Iraq, March 31, 2004

Courtesy of Stanley Greene, Black Passport

“I’m an observer, I’m not an objective observer though, but I’m an observer. I feel it’s very important for journalists to go to these hell holes and photograph or write or do radio or whatever because I still believe that the public wants to know.”

LM: You are doing a good job at humanising the war on both sides, what affords you this level of empathy with combat on both sides of the fence and civilians alike?

SG: Each war has its’ own pull. Susan Meiselas, for example, photographed Nicaragua; she wanted to show the situation that just because they were Communists, they were not evil. I mean, my driver is an insurgent, OK, and he would say to me things like “You know, you have an Islamic heart”, I don’t but because I could listen to him he felt that I was sympathetic and I was sympathetic to a degree, I understood the complaint. And, you know, I think that when you do these kinds of stories you have to ask why.

I mean, I’m from New York. When the World Trade Center was bombed I was like everybody else, I said “Let’s go get those ragheads, let’s go bomb them back to the Stone Age”. I got an assignment from Newsweek, 9/11 happened and I was sent to Afghanistan. I got the assignment on the 13th, I was in Tajikistan on the 13th and by the 17th I was in Afghanistan.

When I got to Afghanistan I saw the conditions and I had to deal with the Northern Alliance, who were very difficult, and I had time to think about it and the first thing that struck me was “My God, what an incredible piece of evil genius! What a cold view of the world!” Here is a man who literally saw human beings as something that you throw away. His main purpose for them was that they were only necessary for the plot, so that the planes would be fully fuelled when they took off. Other than that, they were not important. And then you think I grew up on James Bond, we always had these criminal masterminds and we always giggled. But in reality, Bin Laden became a kind of James Bond villain. If you really think about it in that context he became that James Bond villain. How could this possibly happen? Then I started to ask myself “Why would someone hate us so much to come up with such a monstrous plot, why would they do that?” And the more I thought about it the more I was convinced that somewhere along the line, we pissed off the world, this world, the Islamic world. Then I thought about it even deeper, I said “What would be the purpose, just being so angry?” and I realised Bin Laden’s plot is much more insidious, much more evil, because in an interview before I guess he went to ground, he said that “One day the world will understand and fear Islam.” And he’s right. After 9/11, you could go into bookshops; people were talking about it, reading about it. We know more about Islam than we ever knew before; we know, in fact, more about Islam than we know about all the other religions now. And that… in a way he succeeded, he won, and the fact that we haven’t caught him, he continues to win. Christiane Amanpour from CNN had this documentary, The Footsteps of Bin Laden on CNN, they’ve showed it, I don’t know now, 14? 15? 16? times? Again, he’s won! Because he’s presented as a very charismatic figure, he’s been elusive; he makes George Bush and Tony Blair look like midgets. And this man is evil; he is the enemy we want. Look, Russia wanted to demonise Chamil Bassaiev and say that he was the Bin Laden of Russia but he was no Bin Laden. And, I can’t say his name properly… Zacarias. I mean Zacarias Moussaoui was over the top, he was pure evil. But he’s no Bin Laden, he was a thug. I still question… the one thing that still bothers me about Bin Laden is his… in one sense you see this calm individual and yet he has all this anger inside of him. There’s a film that was made years ago called The Peacemaker with George Clooney and Nicole Kidman… whacked plot, but the quote in it that always struck me, she says “It’s not the man that has a thousand bombs that scares me, it’s the man with the one bomb.” And that’s Bin Laden, he’s scary.

LM: What do you think your role is ?

SG: I’m an observer, I’m not an objective observer though, but I’m an observer. I feel it’s very important for journalists to go to these hell holes and photograph or write or do radio or whatever because I still believe that the public wants to know. The problem is that the public is also becoming a little bit fatigued; we’re not giving the public much hope. And in Iraq I think it’s very important to expose the, what is it? The connerie ( bullshit) that goes on there and I said recently to someone and they got vey upset with me, but I said look “You have to really understand this, I’m a pacifist at heart. I hate war, I think is horrible, I hate the fact that people die, innocents. But here we are, the Samurai, when a Samurai soldier pulls out his sword half way he is obliged, generally, to pull it all the way untilit’s finished when he puts it back. And the Americans are playing this game where we want to be good guys and we have a civil war where innocent civilians are being killed daily and the numbers are high. We’re not talking two or three anymore, we’re talking 50, you know, 25. We’re talking huge numbers of civilians in one day being killed because of this civil war. We have more people that have died in this so-called peace than you had in the original invasion. So we have to stop and say “Ok, we have to be the real bad guy. Let’s find one of those villages that we are thoroughly convinced that the insurgents are there and level it to the ground. The Sunnis and the Shiites will hate our guts for it, they’ll say we’re evil or bad but we will then become the bad guys that we are. We have to stop making believe we’re the good guys because we’re not, we’re the bad guys and we have to be the bad guys so we can stop this civil war, because this civil war is killing civilians. Let’s put it in the right playing field. The playing field is that the American military machine has to be hit. It’s as simple as that, and we’ll do a great job. We’ll go in there and clean that country right up. And then we’ll go out of there and then you’ll move the peacekeepers in there and we’ll deal with it. But, you keep this thing going on, it’s just literally going to flow all over the place and I’m tired of seeing babies and women and old people being caught up in this mess. They have no guns, no bullet proof vests, they have no helmets, they have nothing. And they are the ones winding up on the morgue table.

The road to Samashki in Chechnya, 1996 @ Stanley Greene

“And the destruction is unbelievable. Whole neighborhoods just… you know I spent ten years in Chechnya and I know that it took the Russians a long time to do but in thirty seven days they had flattened the south.”

LM: Can the press have a positive impact on these issues?

SG: Well, I came back from Lebanon and in Lebanon you know, pardon my language, it was a goatfuck. I mean, you had all these photographers tripping all over each other trying to raise the bar because their magazines were insisting on it and the people had just lost their minds. You know, I was sitting in a room (I won’t mention any names) and Cana had happened, I was in Beirut and everyone was saying “We have to go down there because there’s going to be another Cana and we don’t want to miss it.” I was like “What? You don’t want to miss it?” If a rocket hits another building, people are going to die and you don’t want to miss it! I mean, I want to miss it, you know. I don’t want to see anymore dead children being carried out of a place, but if it happens, if I’m there, it’s my job to report it but I’m certainly not going to wish for it, I’m not going to say “Oh yeah, I really want this to happen so that I can get my picture.” You know, it was like everyone when they came back “Did you see any bodies?” “No, didn’t see any bodies, got no bodies. Got some guns!”

We have reached the point where we want to satisfy the bloodlust of the public to the point that we no longer have respect for them. That’s where we’re at. So, for this story I did for Nouvel Obs, I went and I wanted to photograph the victims, I wanted to track down the stories, I wanted to wait until the dust had cleared and I found, for example, a young girl who was shot in the back seven times. Her mother had lost eleven members of her family and watched her daughter die in her arms. They had two houses; the daughter had gone next door to get some toys for the children to quiet them because of the bombing that was going on by the Israelis. The Israelis had infiltrated the first house and gone into the kitchen and set up a post. She had come in and maybe they thought that she’d discovered them and was going back to tell the others, who knows, but they shot her. She died in her mother’s arms. The Israelis discovered that the mother was outside with this dying daughter. The mother drags the daughter next door to the other house; the Israelis chased them and literally fired the whole door and window full of bullets with women and children inside. Evidently, the Hezbollah must have them heard them and came in and shot back at them and they escape. A man is sitting in his house in an area totally under the control of the IDF, he’s…the house…the picture…I mean it’s an unbelievable photograph, the whole house is totally blown up but the Israelis came in and put a trip wire into the house because his sons are Hezbollah. He’s staying in the house waiting for the sons to come back because he doesn’t want, you know, they don’t know where he’ll be. I see these boots sitting there, move a chair and there’s the pressure mine with the clip on it and it’s like a cat could have knocked it off. I went and found the UN who were up the road, brought them back, showed it to them, he ran out of the building, out of this destroyed house and I had to bring him back. I said “Look, if you have to put a gun to this guys head, you have to get him out of here because this place is going to blow up!” So those are the kind of stories. Then I kept going in these “villas” and they were totally booby trapped. A cleaning woman goes up there to pick up the towels, which were very bloody because the Israelis were also the place also as a kind of hospital. And if she picks it up it’s going to blow up. A satchel of bullets, pick it up it blows up. A photograph with a wire attached to it, of the family, of the house, it’s on the floor. They’re going to pick it up off the floor. Boom! That’s murder, that’s not war, that’s murder. So that’s what I photographed. I tried to show that Israel is guilty of war crimes. Yes, yes, yes. Hezbollah is guilty of war crimes too. It’s not an even playing field but when you add it all up, Israel, they killed a hell of a lot more than Hezbollah did. Fact.

And the destruction is unbelievable. Whole neighborhoods just… you know I spent ten years in Chechnya and I know that it took the Russians a long time to do but in thirty seven days they had flattened the south. After you get past the mountains it’s just flattened. Southern Beirut just looks like Grozny, but it took two, three years to put Grozny that flat and they did it boom (clicks fingers) in a matter of days. And yet, what was really amazing, the Christians came back from their summer vacations, they’re out on the streets and everything, you have, I don’t know what, fifteen, ten minutes away Southern Beirut that looks literally like a war zone, like Dresden if you want, and these Christians are saying “Well, it’s they’re fault, they brought it on, they live like Africans, all they do is make babies.” (Sighs and shrugs his shoulders). Oh yeah, it was amazing, amazing!

I was planning a huge story on Chamil Bassaien for Newsweek, we had been planning it for a really long time, it was very secretive. Strange events happened. I was in Azerbajan and someone stole my cell phone. Then I went to Moscow to do a story about NGOs against Putin, someone stole my agenda which I never leave, it’s like my bible. Then I came back to Paris and somebody broke in to my apartment, smashed down the door with a lot of force and took the computer and hard drive but left the DVD player, watches, rings, cameras, lot of stuff. The police came and said it was a robbery made to look like a robbery. Soon after that Chamil Bassaien was killed. I don’t know. Coincidence? I don’t know. But there were people in Azerbajan who knew that we were meeting with the Chechnen commanders that were setting up the trip. So you never know, you never know. So now the Chechnens are a little weary of journalists because every time journalists reach out to one of their commanders the commander winds up dead.

LM: What do you think is changing in the way story are covered ?

SG: I’m taking a young girl as an assistant who’s coming out of Grozny. There is this group bringing students to study in France. So she’s going to ork with me because she wants to be a photojournalist, which is really, really great because now maybe is the time for the people of the country to cover their own stories instead of sending all of us. They live there, they speak the language, they’re willing to spend the time. It is dangerous but, I mean, think about The Resistance you know. Sometimes, to cover stories you have to have a real understanding of what your’e covering and unfortunately in, I don’t know, the school of journalism today we forget to teach them about maps. I think that the quality of journalism has gone down. In Iraq, for example, you have people using the translator/fixers. They are the journalists, they come back with the report on tape recorders or photographed on digital cameras and they give it to the writer who sits in the hotel and writes it up and they send it out. They are becoming the journalists. I mean, in Russia for many, many years photographers like Chris Morris, myself or Peter Turnley, we went to Russia to do the stories. Now you have Russian photographers, journalists, writers. They do the stories. I think it’s healthy in one sense but yeah, you’re right, it’s a problem because they are more vulnerable to attack, they can be arrested or killed, especially in Africa where journalists tend to go missing quite often. (Shrugs shoulders) I have no answers. But I do think it’s…let us say that hopefully it’s a good direction for peacetime. For peacetime, let’s say that.

LM: Hopefully.

(All rights reserved. Text @ Laetitia Martinez and ASX, Images @ Stanley Greene)