Farmer’s Son with his Nursemaid. Marico Bushveld, December 1964, 1964

“During the years of apartheid, I was concerned with trying to…with exploring why people valued this peculiar and evil system and how they expressed those values in their homes, in themselves, in their bodies, in the things that they built.”

Interview conducted by Laetitia Martinez, recorded by Cedric Batifoulier in Arles Festival , France. On the occasion of the 2006 Retrospective of David Goldblatt, curated by Martin Paar.

LM: What do you think your photographs represents, do they have any functions?

DG: When I was much younger, when I first started taking photographs, I wanted to tell the world about what s was happening in south Africa because at that time, the magazines in the world and the press were not really interested in us and it seemed to me that terrible things were beginning to happen in south Africa and I needed to tell the world about this. But quite soon I realised that this was not what I was best able to do… I wasn’t… I’m not a good photographer of events, I’m a coward, I run away from violence, I don’t like violence and confrontation. And I’m not interested in events as such as a photographer, as a citizen of the country yes of course I am. But as a photographer, I am interested in the causes of events.

LM: What attitudes lead to events?

DG: And so if you asking me what function did I think my photographs might perform, I find that a very difficult question to answer because I don’t think that I ever influenced anybody to do anything or not to do anything. Because I don’t regard myself as a missionary. I wasn’t err… I didn’t regard the camera as a weapon in the liberation struggle as some of my colleagues in South Africa did. It was a dialogue in my photography between myself and whatever I photographed and my compatriots, my fellow South Africans. I realised roughly in about 1968 that I wasn’t really interested in talking to people outside south Africa because the situation was too complicated and the things that I was interested in photographing were too oblique, too ingrown, too convoluted for people who were not born into the country to understand .I found when I tried to show these photographs outside south Africa it was like trying to explain jokes. And of course, once you explain a joke, it’s no longer a joke, it’s no longer funny.

LM: How did you balance your work between the white and black community, what was your attitude, your interrogations, your way of working? Basically,what was your photographic journey from the dying gold mine to “Pulling out of Pretoria: the 7:00 p.m. bus from Marabastad to Waterval in KwaNdebele” and South Africa: The Structure of Things Then.

DG: During the years of apartheid, I was concerned with trying to…with exploring why people valued this peculiar and evil system and how they expressed those values in their homes, in themselves, in their bodies, in the things that they built.

Well In the very early work, there is work, there is photography that I did on Afrikaner people in South Africa, and these were the people who were the supporters of the apartheid government. And I became very interested in trying to understand better who these people were and what their values are and so on. And then I photographed the dying goldmines of south Africa, I was born and grew up in a town surrounded by gold mines and eventually I worked with the writer Nadine Gordimer on that particular essay .( i.e On the Mines. With Nadine Gordimer. Cape Town: C Struik, 1973.)

“And my reason or my interest in this was based on a question: How is it possible to be law abiding, normal, and descent in a society and in a system that is fundamentally evil?”

And then through my years of photography, I have worked on essays. I have very seldom worked in single pictures. Almost everything that I have done in my personal work has been around a group of photographs relating to a certain subject that became of interest to me. So at some stage, I became interested in photographing people’s bodies. I had been doing a lot of portraits in Soweto and Johannesburg of black people and white people, and while I was doing them I became very interested in their bodies. I would see a girl’s hands and her arm and maybe her breast or hip or whatever it was and so then I decided just to look at that and see what came out. Would it be of any interest? And for about 6 months that all I did, I became obsessed by people’s bodies. I would go to people sitting in a park or public place and say “do you mind if I photograph your hands “or something like that.

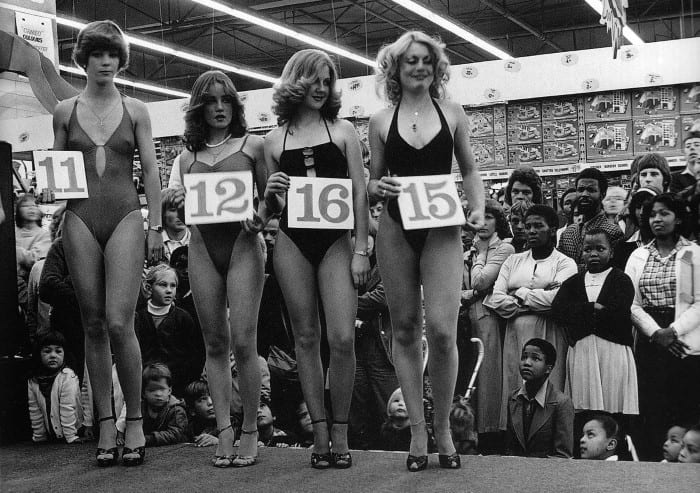

And then I wanted to look at my own society, middle class white society. I grew up in a middle class white community called Ranfontein and I suppose I could have gone back there but I did not want to do that because it would have been too painful and also very difficult. But I went to another town where they were a similar community: Boksburg. And I spent about 6 month there in 1979 and 1980 just photographing life in this white community. And my reason or my interest in this was based on a question: How is it possible to be law abiding, normal, and descent in a society and in a system that is fundamentally evil? This was my question to myself really, I could not answer it, there’s no answer because those people I photographed in Boksburk were ordinary people and You’ll find similar people in Arles, you’ll find them in Paris, you’ll find them in new York, in Chicago, in Goteborg in Sweden, wherever you go in the world you’ll find people like this .But here were people living and collaborating with a system that was fundamentally evil. So I tried in those photographs to withdraw myself, I did not want to be present in the pictures. I wanted these pictures to be completely a reflection of life in that place at that time. So you never see me, the photographer, in those pictures. They’re always people interacting with each other.

The commando of National Party supporters that escorted the late Dr Hendrik Verwoerd to the party’s 50th anniversary celebrations, De Wildt, 1964.

And then I did the photographs that you have mentioned of the people riding the buses those were very… I mean that did not take much time in terms of the photographs, I made a few trips on the buses and those were perhaps the most moving times that I’ve ever had, traveling on those buses with those people because some of them travelled for up to 8 hours a day just to go to work and come home. The grain is very strong because there was no light .

Then I spent ten years photographing structures in South Africa and another five years doing research and writing about those structures. So fifteen year all together on the one project.

LM: Can you tell me a bit more about this obsessions with structures?

DG: As far as I know, I don’t know of any other work in photography anywhere in which people have looked at structures as expressions of value. They have looked at structures as architecture, as art, as expressions of culture but not as expressions of value. “Why is a church built a certain way?” Now in Europe, you have magnificent churches, my exhibition here is in a beautiful old church dating perhaps from the, I don’t know, the sixteenth century, seventeenth century? if I were to ask somebody here in Arles:” why is that church built in that particular way?”” what does it express?” they would not be able to tell me. And the fundamental reason in my opinion is that in Europe you have centuries of art and of culture, layer upon layer upon layer and you have forgotten already what lies at the bottom of the layer. In South Africa that is not the case. It’s still a very young society. We have built our structures to express ourselves in a very naked way. Our churches are, in my opinion, an amazing expression of values. The Afrikaners were the most powerful, energetic group of whites in the country. They pioneered the drive into the interior, they fought against the black people who occupied those places and conquered them and then built their churches in those places and expressed their conquest in those churches. I could draw a graph of the political fortunes of that folks, of that people and correlate it with the architecture of those churches. In the nineteenth century, the latter part of the nineteenth century, their churches were beautiful like European cathedral. They were designed by European architects because in South Africa there were no trained architects. So they were based on Dutch, German and French sacred architecture but they were also expression of the new found strength and freedom of this folk. They were celebratory of the rising strength of this people. Then came the anglo-boer war. Then the Boer, these Afrikaners went to war with Britain and Britain eventually conquered them, broke their spirit, broke the economy, burnt their farms, put their women and children in concentration camps. Those were the first concentration camps. And the churches that they built after that for a while were very much the same. They were based still on those earlier churches but much quieter.

Three women at 39 Soper Road, Berea, Johannesburg, May 1972

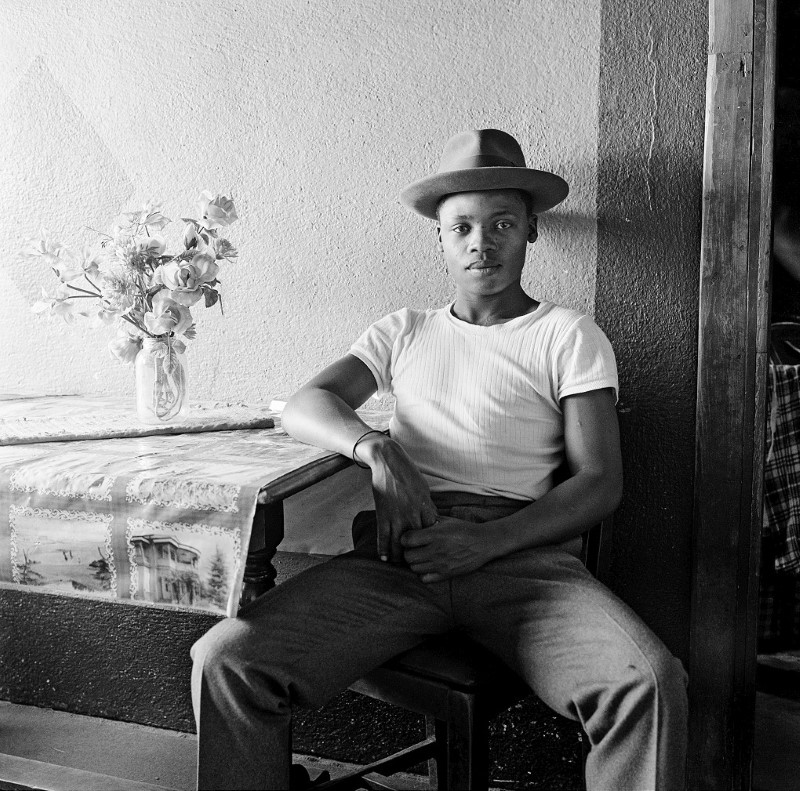

Young man at home, White City, Jabavu, Soweto (2_12560), 1972

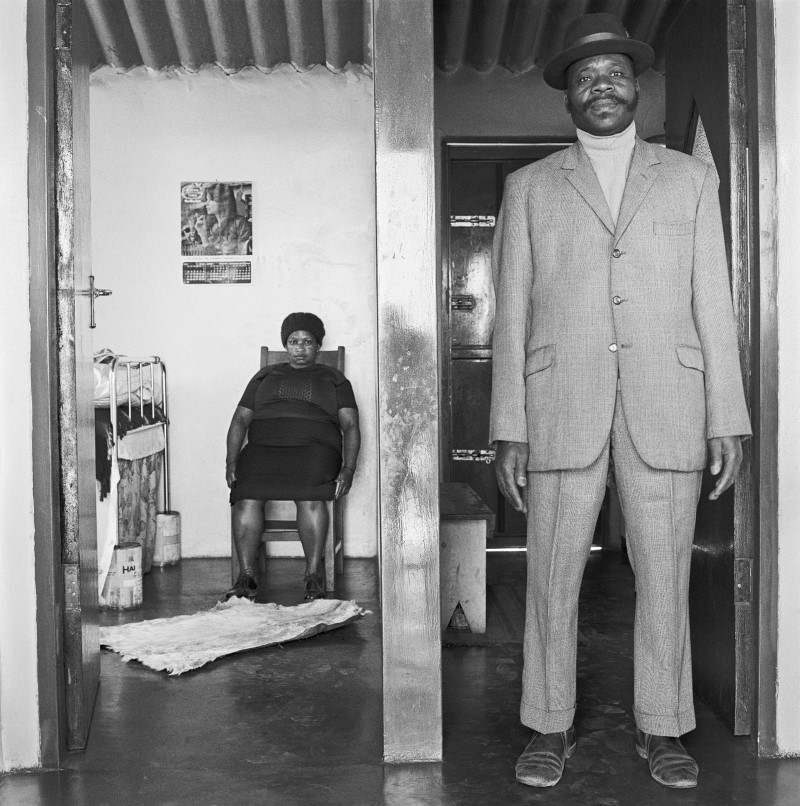

Sarah and George Manyani in their house, Emdeni Extension, Soweto, August 1972

A domestic worker’s afternoon off, Sunninghill, Sandton, Johannesburg

Then in the 1930’s, the political movement grew among the Afrikaners to express Afrikaner nationalism which was a rising force. This rising force was then expressed in a number of very potent folk movements. I won’t get into that but the church architecture then changed fundamentally. At the beginning of the second world war, just two churches were built by one man, an architect and that changed the whole picture of Dutch reform church architecture, Afrikaner protestant architecture because he broke away completely from the European model, he built a modernist structure to express the modern Afrikaner and the unity of this Afrikaner folk that was now taking place. This new political strength .And after the war, the Second World War, those churches just took off like fireworks. They became triumphal because they expressed the strength of apartheid. They were triangulated with huge phallic spires, great big windows because the liturgy of the church was based on the principle of “the word of god must go out “, you must preach the word of God. So the word of god was preached by the preacher, he stood in the apex of the church which is like a megaphone. The church was like a megaphone, and in front of him was his congregation and there were these big windows so that his word could go out to the world and the world that he preached was the word of apartheid. And then came the 1970 and 1980 when the Afrikaners folk believed that they were being attacked by the rest of the world, but the communist forces and the forces of liberation and humanitarism and the churches then became like this ( closes his hand to form an egg). No windows in the outer walls and protecting the folks. The folk were now inside and the “word must go” out but it only went out to the folks inside.

I know that some of my photographs were not liked by my compatriots; they think they are terrible photographs because perhaps they tell too much or too little, I don’t know, am not sure. I’m photographing real things but at the same time it is an abstraction from reality. It has always been abstraction from reality. It has never been a duplicate of reality.

Thank you.

Transcript realized with the authorization of oc-tv Toulouse, France.

(All rights reserved. Text @ ASX and Laetitia Martinez. All images Courtesy of the photographer and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg © Copyright 2012 David Goldblatt)