“I always thought of photography as a naughty thing to do, that was one of my favorite things about it, and when I first did it, I felt very perverse.”

– Diane Arbus

By Gerry Badger as a collaboration with ASX, Originally Published in Phototexts, 1988

The principal issue raised by the remarkable photographs of Diane Arbus seems not to be their remarkableness, which few would dispute, but their morality. The very potency of her images, their dangerous, disturbing allure, demands an almost instantaneous moral judgement on the part of the viewer. Her pictures call forth an immediate stance which, it would seem, just cannot remain equivocal, yet which in many cases is tinged with uneasy contradiction. To some, Arbus is seen as the prime exemplar of the fundamental baseness of the photographic act, that act which caters ineffably to the disinterested voyeur lurking in us all. Others laud her for her compassion and her humanity, finding in her work an empathy with a disadvantaged subject matter to rival that of Riis, or Hine, or any of the great photographic humanists.

Photographic morality is an issue of some complexity, particularly where the photograph involves people. For the camera is a liar of immense proportions, and yet a liar of immense plausibility. Every photograph is a fiction, constructed by the photographer. That it is a fiction does not preclude it from telling a larger ‘truth’, but the road to that truth is set with devious pitfalls, flagrant cul-de-sacs, and blatant misdirections. The subject of a photograph, especially if animate, is drawn directly into the photographer’s game. That game might be the Truth Game, but is more likely to be ‘Truth or Dare’. There are few photographs in which the subject matter is wholly abstract, that is to say, wholly neutral. One cannot suspend disbelief for a second, as conceivably one might with a painting or drawing, and imagine that the subject of one’s favourite photographic nude really is Ariadne or Olympia, even the vamp or the virgin. The archetype may have been called for by the casting director, but always it is Miss Smith the photographer’s model – not the myth, not the handling of painted surfaces – with which we must deal, directly and overwhelmingly. As Susan Sontag put it (with the subject of this essay clearly in mind). ‘In photographing dwarfs, you don’t get majesty & beauty, you get dwarfs.’2 Ms. Sontag reveals not only an interesting slip – Freudian or otherwise – in relation to small people, but also exhibits a common prejudice towards photography. It is the ultimate purpose of this essay to refute Sontag’s statement with regard to both Arbus and the medium, but for the moment I shall let it pass, except to say that its implications are twofold. Firstly, as a widely held notion – part truism, part misconception – it means that photography itself is stigmatised by a gap between actual and intended, between what the medium proposes and what it disposes. And secondly, the very existence of that gap imposes a clear moral conundrum.

A family on their lawn one Sunday in Westchester, N.Y. 1968

Puerto Rican woman with a beauty mark, NYC, 1965

The specificity of photography, the imagined lack of any mediation between world and image, places a particular moral responsibility upon the practitioner – the perpetrator of this crime of the fiction that is not a fiction that is a fiction – and by extension upon subject and viewer, accessories before and after the fact. In the main, however, impeachment of the latter might be nominal only. The involvement is strictly secondhand, passive rather than active, for subject as much as viewer. Even when attempting knowingly to conspire with the photographer, the subject generally accedes to the practitioner’s directions, with minimal control over the final look of the image, and crucially, over its dissemination. Subject and viewer may at least enter a plea of extenuating circumstances, but never, never a photographer. A. D. Coleman put it succinctly when he wrote that the photograph made with conscious intent is inevitably a ‘remaking of an event into the photographer’s own image, and thus an assumption of godhead. To live outside the law, you must be honest.’3

All photography is potentially exploitative, photographic portraiture is inherently exploitative.

All photography is potentially exploitative, photographic portraiture is inherently exploitative. The potential for misanthropy invariably thrives whenever one human being has power and control over another. The reality of photographic exploitation might be eradicated only in theory, in the practicable implausibility of subject’s and photographer’s aims coinciding exactly. Until then, apologists for the medium might seek only mitigation, and practitioners proceed with consideration, awareness, and humility. There is, however, I would submit, a question of degree. Exploitation of subject by photographer might be viewed as a continuum, ranging from the mildest at one end to the grossest at the other. Can one therefore define, and quantify, a ‘benign’ as opposed to a ‘malignant’, an ‘honest’ as opposed to a ‘dishonest’ exploitation? We must ask a number of pertinent questions in each case. Precisely how has the photographer ‘exploited’ the subject? Did the photographic transaction take place with the subject’s prior knowledge or consent? What is the purpose of the image? Has the subject been allowed or denied a voice? Does the picture appear to serve the ideological good or ill? (An especially tricky one this). Any answers must be highly contingent, but can play their part in deciding whether we are dealing in a particular instance with photographic morality or lack of it. Few would seem to believe that the medium is wholly beyond redemption. Even Sontag, after roundly villifying all photographs for being morally equivalent – stating that the camera ‘annihilates moral boundaries and social inhibitions’4 – clearly views such figures as Walker Evans and August Sander as being on the side of the angels. Equally clearly, she views Diane Arbus as being indisputably on the side of the Devil.

Identical twins, Roselle, NJ 1967

Our subject herself hardly gets us off to an auspicious beginning in the morality stakes. And yet this artistic hedonism was typical of the cultural milieu from which Diane Arbus emerged, limited by no means to photographers.

Any commentator seeking to list photography’s moralists surely would include Lewis Hine, August Sander, and Eugene Smith near the head of their inventory. Hine’s credentials as a moralist are well nigh unimpeachable. He photographed only to effect social change, his camera a positive weapon in the struggle to alleviate the wretched circumstances of the American worker. Sander’s political persona is perhaps more circumspect, more oblique, but no less creditable. He remains the photographic sociologist par excellence, obsessed with rendering scientifically the physiognomy of the individual as it is marked indelibly by class. Smith is the great photographic humanist, the romantic non-conformist, the lone crusader who fought both against the iniquities of corporate capitalism and for the photographic medium. But Diane Arbus? Can she, by any stretch of the imagination, be counted amongst this company? Or does her work evince a clear immorality by concentrating upon society’s and nature’s victims in a manner wholly devoid of compassionate purpose, exemplifying a distant view that is at once sinister and self-indulgent? To my mind, as one of the minority – albeit a sizeable minority – who would advocate her morality as an artist, any conclusion would seem to hinge upon answers to the following questions. Firstly, does the hedonistic, sensation seeking aspect of the work outweigh its psychological authenticity? Secondly, did Arbus attempt, however haphazardly, to formulate a programmatic interpretation of American mores? Putting it another way, was Diane Arbus fundamentally an honest photographer, and, what does she say to us? Beginning with the first of these questions, there is little doubt that Arbus appreciated what one might term the self-indulgent aspect of the photographic enterprise. It is a factor she herself stressed in her own published statements about her work. Indeed, she would appear to have been an indefatigable player of photographic games and a tireless seeker after camera fodder:

‘I always thought of photography as a naughty thing to do, that was one of my favourite things about it, and when I first did it, I felt very perverse.’5

Our subject herself hardly gets us off to an auspicious beginning in the morality stakes. And yet this artistic hedonism was typical of the cultural milieu from which Diane Arbus emerged, limited by no means to photographers. Her whole being was shot through with Greenwich Village bohemianism, that nineteen-fifties New York art scene cocktail of surrealism blended with expressionism, spiced with narcissism and sponteneity, a lifestyle and an artistic philosophy that conceived of the world as a succession of spicy stimulii to the senses rather than as an imperative for moral action. However, to suggest that Arbus’s predatory penchant wholly dominates the ethos of the work is, I submit, a mistake. As is reading too much into the coy pronouncements of artists. Many statements made by Arbus – exaggerated, self-deprecating, slightly mocking – sound nothing more than a good old-fashioned New York ‘put on’. Diane’s craving for the hunt, her unabashed revelling in the thrills of the chase, seems no greater nor lesser an impulse than that of any artist in search of a subject. Going out into the field, entering lives for a brief while and then leaving them, was necessary for the work. That is the nature sometimes of the artistic quest, but it is a nature wholly condemned by Susan Sontag:

‘Being a professional photographer can be thought of as naughty, to use Arbus’s pop word, if the photographer seeks out subjects considered to be disreputable, taboo, marginal… Photographing an appalling underworld (and a desolate, plastic overworld), she had no intention of entering into the horror experienced by the denizens of those worlds. They are to remain exotic, hence ‘terrific’. Her view is always from the outside… Arbus was not a poet delving into her entrails to relate her own pain but a photographer venturing out into the world to collect images that are painful.’6

Boy with a Toy Grenade in Central Park, (1962)

In the foregoing, Sontag harps upon the predatory, colonising urge of the photographer as if it were unique. She might write in the same vein about the painter, the film-maker, the novelist, the sociologist. How often does the writer engage in field research and interview subjects outside his or her social milieu? How perverse and naughty did Degas feel when making his justly celebrated monotype series on life in a Parisian brothel? Did Sander and Hine work any more from the ‘inside’ than Diane Arbus? However, I am not seeking to absolve her merely by indicting others. Whilst the vicarious pleasures of disinterested observation – in a word, voyeurism – might be acknowledged, the purpose of the serious artist is surely more complex, profound, and intrinsically worthwhile.

Much of the negative criticism of Arbus focuses, in one way or another, upon her aggression.

Much of the negative criticism of Arbus focuses, in one way or another, upon her aggression. Firstly, there is her presumed aggression towards her subjects. This is usually characterised as extreme, an easy indictment to make, since Arbus violated, or rather extended the canons of acceptable distance between photographer and model by frequently moving in perilously close. However, since almost all of her images were made with her subjects’ consent, the charge must be levelled indirectly. This is effected by maintaining that the aggression of Arbus was disguised by soft words and careful dissembling. It was, in short, aggression by stealth, a typical strategy of many photographers. Arbus, it is claimed, by maintaining a generally frontal stance and manoeuvring into close proximity, created an ostensible intimacy in her pictures, and thereby a false aura of empathy with the pictured. This bogus theatre of empathy is reinforced by the formality of the picture-making situation. Arbus’s subjects face the camera stiffly and bravely, often, it would seem, seeking to assuage any doubts with a frank stare. Mostly, they seem in full, if somewhat uneasy acquiescence with the photographer. But, say the detractors, they could hardly know what Arbus was doing. Her ‘victims’ were duped, evidently with some suspicion on their part, but generally left unawares that they indeed were victimised by a thoroughly unscrupulous predator. The photographer’s game, according to her negative critics, was to court this awkward intimacy specifically in order to make her sitters look strange and demented. As Ian Jeffrey wrote in his review of the major Arbus retrospective of the early nineteen-seventies, the posthumous exhibition which did much to establish her reputation – or perhaps fuel the controversy:

‘…There is a stress on the grotesque, many of the figures are ugly, their settings are mundane and their actions are perturbing… Virtually everything she pictures is strange and in the course of being fixed as a picture it becomes stranger.’7

Diane Arbus

To some, Arbus effected this negative transformation in virtually every picture she made. To others, it was more selective, deliberately and peculiarly inverted. Perhaps the most widespread of comments on Arbus is that she made ‘normals’ look like ‘freaks’, and, conversely, ‘freaks’ look like ‘normals’’. Almost every commentator on her work mentions the division of Arbus subjects into two groups, one, the chosen – middle class, Middle America, relatively affluent – and two – the misfits, the poor, the racially stigmatised, the physically handicapped, the psychologically disturbed, the sexually deviant. She constructed, in the words of Ian Jeffrey, ‘a perverse parody of a social structure.’8 Jeffrey is, I feel, unduly harsh in his choice of the adjective ‘perverse’, but he is one of the few critics to suggest a potential reading of Arbus along social lines. Few have viewed this clear labelling of types in Arbus as an invitation for sociological speculation. Fewer still have asked if Arbus may have intended to make comparisons between social groups. Her work is assumed automatically to have been wholly egocentric and inward looking – typically nineteen-sixties, typically American, typically internalised ‘women’s’ art.

Yet one interesting parallel to Arbus, occasionally mooted by critics, is George Grosz, that savage chronicler of Weimar Republic mores. Arbus herself, from an early age, admitted to a liking for his work. Certainly, there is little doubt that Arbus could be resolutely fearsome when she desired, utilising the caricaturing power of the camera to satirise quite as cruelly as Grosz. She may not have been especially politically minded, and in no way active in political life, but in her images of political demonstrations, such as Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a pro-war parade, NYC (1967), we would seem to be given an unequivocal statement of her viewpoint, at least on that singular issue. We are given a clear demonstration of just who she considered a ‘freak’, just who was beyond the pale and a worthy target of deprecation. Here, a tentative link with Grosz would seem apparent. The mediation, the expression of the artist’s purpose within the pro-war marcher image could hardly be mistaken. But such mediation is much less obvious in other Arbus images and prompts a question. Can it be that Grosz’s savaging of the human form is praised simply because he was a painter, and therefore at least one degree removed from the actuality he portrayed? Is Arbus the photographer denigrated because her mediation was too subtle to be perceived by naive viewers, by even a Sontag? Is subject confused with image by many viewers, and Arbus seen only as the wilful recorder of distasteful sensation, and not as a conscious, cogent commentator upon the human situation? Is the issue obscured by the apparent rawness of the photograph’s reality, an irrational fear that takes us back to the stealing of souls? As Stanford Schwartz has observed, ‘the nugget of reality in a photograph will always subvert the photographer’s intentions.’9 Is Sontag forgetting, as Schwartz reminds us further, that the ‘process of testing a work, to see how much of it is emotionally and intellectually fake, and how much true, goes on whatever we look at or read or listen to.’10

It really would seem that Sontag at times is blind to this salient point, and blind also, to the pictures’ actuality. She states, for example, that Woman with a veil on Fifth Avenue, NYC (1968) is ‘characteristically ugly’,11 a conclusion that would seem to have been prompted by the closeup clarity of the woman’s rather fleshy face as rendered by electronic flash. But is Sontag reduced to such a blindly literal view? ‘When you photograph dwarfs, you get dwarfs.’ Is it simply her own prejudice that causes her to equate ageing with ugliness, and promotes an unwarranted misreading of this, and by implication many other Arbus images? Does Sontag’s own imagistic naivety cause her in turn to accuse Arbus of an ill intentioned naivety? For in my view the veiled woman of Arbus is rather handsome. Sontag might have pondered how Richard Avedon might have treated such a subject. As Alfred Appel Jr. has noted, we may presume that ‘this woman’s cultural expectations are positive’.12 Indeed, the image would seem to be about confidence and privilege rather than ageing. The image’s formal qualities, the mixture of sensuous textures, of fur, lace, and glistening skin, speak of affluence and smugness, not mortification and decay. Arbus has commented, certainly, but she has not ‘uglified’, nor savaged unduly. I know of few photographs which parody better the self-satisfaction of a particular kind of American bourgeois matron, a critique which, as Sontag notes accusingly, might be personally motivated on the part of the photographer. But what art, at root, is not? However – and this is a central problem with the formalist ¬documentary school of sixties and seventies American photography, the information that prompts one to read an image in socio-political terms may simply have dropped off in the picture frame by accident, unmediated and unintended by the photographer. Are, for example, Lee Friedlander’s startling portraits of factory workers apparently welded to the machines they operate primarily refined exercises in cute, surrealistic camera collaging, or are they the finest images to symbolise the contingent realities of factory existence since those of Lewis Hine?

So, in just three images in the Arbus oeuvre – the pro-war demonstrator, the veiled woman, and the topless woman – we might see three widely differing rhetorics in the photographer’s expressive armoury.

Let us consider another image by Arbus, her superb Topless dancer in her dressing room, San Fancisco, California (1968). During that portrait session, the photographer probably shot at least one roll of film, possibly a lot more. From a number of possibilities, she then selected, perhaps even directed the image she would print. An image in which the subject just happened to smile wryly, in which one finger just happens to be fondling one of the primary tools of her trade, her left breast. Add to that the glitter of her gown and her heavily made-up face, contrasting starkly with the surrounding dressing room squalor, and we have a picture laced with irony. And it is an irony in which the subject, by her very gesture, colludes willingly. It is an irony every bit as warm and empathetic as that displayed by E. J. Bellocq’s splendid Storyville prostitute of 1912, who mockingly toasts herself with a glass of whisky.

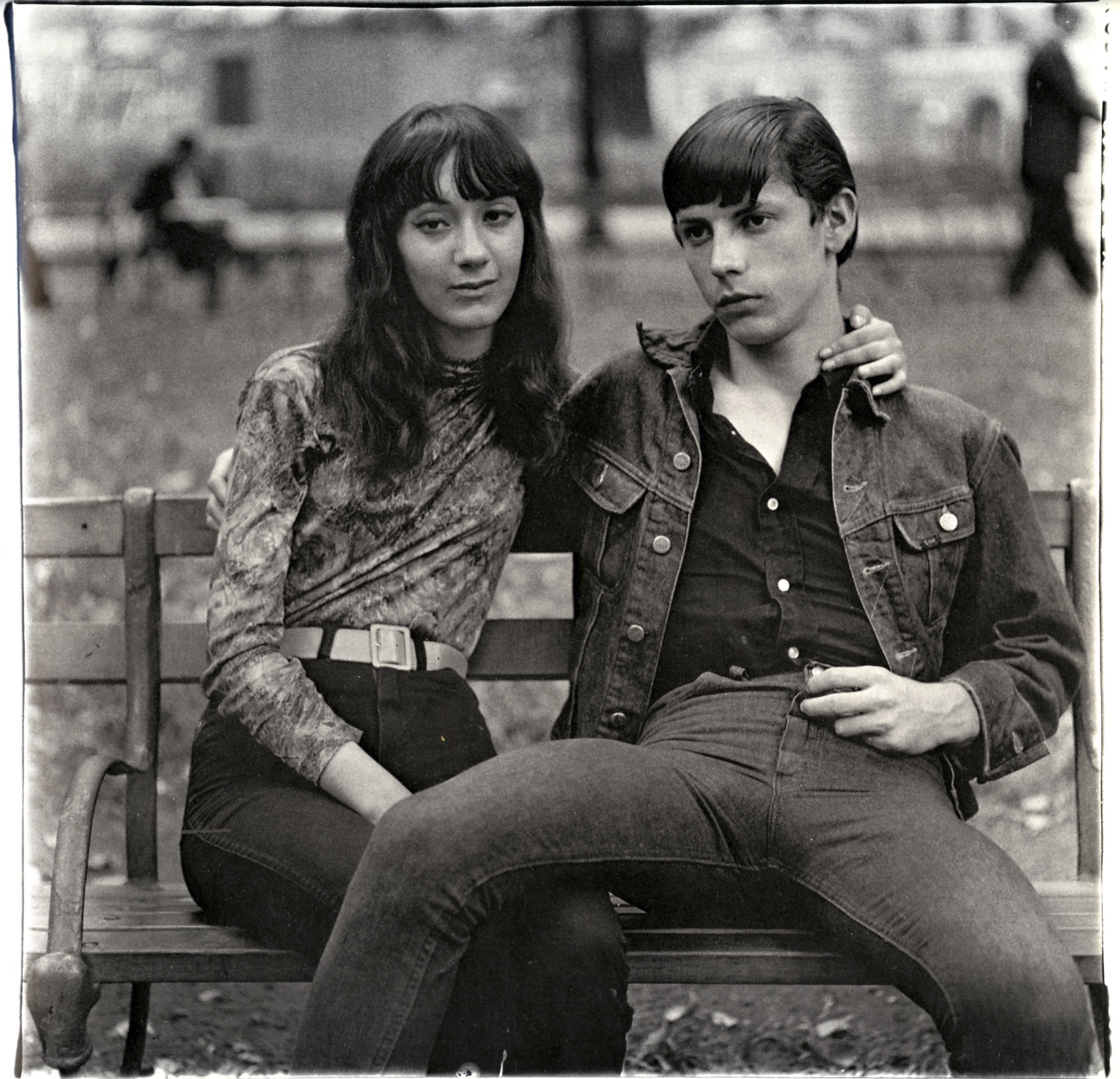

So, in just three images in the Arbus oeuvre – the pro-war demonstrator, the veiled woman, and the topless woman – we might see three widely differing rhetorics in the photographer’s expressive armoury. Firstly – savage satire. Secondly – firm but not cruel disapprobation. Thirdly – warm, collaborative irony. I could continue. There is the unsentimental, but manifestly sympathetic straightforwardness of Mexican dwarf in his hotel room, NYC (1970), an image in which, contrary to Sontag, one reads humanity first and dwarf only in a secondary capacity. There is the gawky joy of Girl in a shiny dress, NYC (1967), no Vogue or Harper’s starlet this, but no monster either, just a girl having a good time. There is a further example of the artist’s disapprobation in Teenage couple on Hudson Street, NYC (1963), where the deprecation seems directed not at her subjects but at a society which forces children into such prematurely adult roles. And there is the pathos of Woman on a bed with her shirt off, NYC (1968), a shattering picture that by virtue of its utter poignancy surely refutes the all-too-easy myth of the calculating outsider or blatant opportunist.

Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a pro-war parade, N.Y.C. (1967)

Let’s suppose however . . . Let’s suppose that the primary source by which we know the work of Diane Arbus, the posthumous Aperture monograph,13 was titled differently. Let’s suppose that Diane Arbus – An Aperture Monograph, was entitled something like American Photographs, or The Americans. Surely we would be inclined to temper our formalist/ psychological reading with one more related to the social documentary. And if we indeed look at the monograph less in terms of a series of individual, stylistically related images, and more in terms of a cogent entity, what do we find? I think we find something interesting. We find, I believe, a document – a personalised document perhaps, but no more so than that of Robert Frank in the preceding decade. We find a work in which the commentary upon the social structure – though couched in personal terms and mediated through the psychological – is precise and intelligently considered, and a deal less ‘perverse’ than many commentators have surmised. The Aperture monograph was published in 1972, shortly after Arbus’s death. It was edited by Marvin Israel and the photographer’s daughter, Doon Arbus. The book, considering its specialist nature, has been a phenomenal success. It has sold in excess of 100,000 copies, and has been instrumental in fuelling the lurid posthumous legend of Arbus. Perhaps from a feeling of disquiet at this, perhaps because more Arbus material remains to be released on the art market, perhaps because the book has been so influential, but Israel tended to disparage the monograph in later years, as in his introduction to the book on her magazine work:

‘Guided by her own selectivity, the monograph attempted to portray, through her words and pictures, how she saw herself as an artist. As a collection of some of her best work and a clue to her intentions it served a purpose. But as a depiction of a career, for which it has since been held accountable, it is misleading.’14

That may be so, but the book remains a powerful, complex, and cohesive statement, and much more than a collection of ‘greatest hits’. Indeed, I would rate it as one of the most cogent volumes of ‘poetic documentary’ photographs to be published since Robert Frank’s The Americans. Certainly, it is a partial, internalised view, but it is a view of society, or more accurately of experience in society. But then that is precisely what Frank’s book was. John Szarkowski has written aptly:

‘For most Americans the meaning of the Vietnam War was not political, or military, or even ethical, but psychological. It brought to us a sudden, unambiguous knowledge of moral frailty and failure. The photographs that best memorialise the shock of that new knowledge were perhaps made halfway round the world, by Diane Arbus.’15

But how might we define Arbus’s theme? As Szarkowski suggests, the tenor of her work was psychological rather than ideological or sociological. Her theme was not overtly political, and hardly sprang from any deep seated ideological conviction, yet Arbus certainly had an interest in the workings of society, specifically, an interest in human relationships as they are acted upon by society. This comes through in the work generally as a sense of alienation and disaffection, a result perhaps of personal failure in her own relationships, one might be tempted to say. But surely it is also a reflection of moral failure in society, a reflection of how the success and power orientated ethos of America – and indeed the modern industrial/capitalist world – both atrophies personal human relationships and automatically marginalises those perceived as less than successful or powerful.

Let me quote two observations about Arbus, from roughly opposing views of the photographer. Nevertheless, they would seem to agree upon the primary leitmotif in her work, upon her oeuvre’s intent if not its effect. Firstly, Amy Goldin writes:

‘Arbus’s central theme is the futility of artifice. . . the distance between what is chosen and what is given.’16

Secondly, Ian Jeffrey once more, musing upon a statement the photographer herself made in the introductory text to the monograph about the ‘gap between intention and effect’:17

‘It is though she is obsessed by the peculiarities which arise from the distance between intention and effect, and having established this as her peculiar insight documented it where and whenever it was found.’18

There are divisions in society other than those of class, ideology, race, or gender – smaller divisions which cut across the larger in many ways. There are those blessed or cursed with a minority sexual orientation, those with physical or mental disabilities, those whose lifestyles, for differing reasons, do not concur with the dominant consensus. To be outside the dominant societal groups, or at odds with the dominant ideologies, is to be marked as being apart. And for those so marked, the majority reserves its disapprobation in one form or another – be that censure light or heavy, tacit or overt, relatively benign or disproportionately punitive. To be seen to ‘challenge’ the norm is to be stigmatised, accorded the position of outsider. The stigmatised, if only in relation to the group which defines their particular norm, form a class apart, a sub-class. Even what at first glance may seem a nominal minor stigma, a peripheral deviation, can have far reaching social implications – quite as much for the individual as the ‘major’ divisions of socio-economic background, race, or religion. ‘Freak’, in short, is decidedly a class issue. Thus the ‘distance’, the ‘gap’ that both Goldin and Jeffrey perceive Arbus exploring, would seem to transcend the purely individual inflection, and address the wider question of stigma in society. The clues or symbols we are asked to decode in Arbus’s pictures relate consistently to issues of normalcy and freak. Time and time again in her work, by means of deliberate inversions and finely calculated absurdities, by drawing and then subverting boundaries between stigmatised and non-stigmatised, Arbus gave voice to, yet also mocked the often ridiculous struggle we put up in order to bridge the gap between intention and realisation, between acceptance and non-acceptance. She focused particularly upon the sometimes grotesque efforts in which we indulge in order to mitigate life’s iniquities and inequalities, honing in upon those institutions of mutual comfort, the club and the tribe. She concentrated upon the often perverse and arcane rituals each ‘club’ – even a club of one – evolves to protect its identity, rituals expressed most vividly in costume and uniform, which both display and yet mask the true nature of the tribal identity. Ritual and costumes outwardly define a role, but Arbus nagged constantly at the sham of many of the roles which we adopt. Her subjects so often are forced, either by nature or society, to adopt the wrong role. They are forced to join the wrong club, cast invariably to play Rigoletto rather than the Duke.

A Jewish giant at home with his parents in the Bronx, N.Y. (1970)

Arbus shows that most of us seek in some way to escape (optimists might say transcend) an undesired self, a self which might exist only inside our own heads, or which might be scarred materially from birth to death, by a cruel nature or uncaring society.

Much of the mock heroism, the bitter irony, indeed the deep pessimism in the work of Diane Arbus would seem to derive from her acute demonstration of this one immutable truth. Her vision was racked with a continuous sense of falling short in life. We are frustrated because we have chosen the wrong role in life, or more frequently, because the wrong role has chosen us. Or we have been ‘fortunate’ enough to have emanated from a milieu of apparent wordly success (like Arbus), we perhaps realise from the outset that the whole performance is a travesty. Arbus shows that most of us seek in some way to escape (optimists might say transcend) an undesired self, a self which might exist only inside our own heads, or which might be scarred materially from birth to death, by a cruel nature or uncaring society. Many remark upon the grotesque qualities of Arbus’s work, seeing it in terms of perverted, voyeuristic glee. Few choose to see it in terms of unmitigated pessimism. Her view of society, of the innate destiny of humankind, is as profoundly bleak and as jaundiced as that of her twin mentors, George Grosz and Lisette Model. Even Arbus’s babies are tainted, bearing the marks of life’s vicissitudes to come, losers from the outset. Yet Arbus was palpably less cruel than Model, and infinitely less prurient than Grosz. Both emigré European artists seemed thoroughgoing misanthropes, who seemed to have viewed themselves, and mankind, as beyond redemption. Arbus’s vision seems heroically tragic by comparison. She was not, I trust, displaying her cynical side when she made the following observation:

‘Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.’19

The question, as always, is whether her sentiments, her assumption of the privileged position as confidante to the stigmatised, her adoption of the mantle of the ‘wise’, as the sociologist Erving Goffman put it,20 was genuine, or simply a strategy. I cannot deny that her own words on occasions leave a degree of equivocation. There seems little doubt that Arbus was inquisitive, acquisitive, voyeuristic to a degree, and certainly aggressive in her pursuit of images. Even when invited, she invaded the psychological space of her subjects to an alarming degree. The central issue is, however, for whom does she ultimately speak? Are her subjects allowed a clear voice? That, to my mind, is the central issue, not just in Arbus, but in all portrait photography. The portrait photographer has been entrusted with a sitter’s identity, with his or her humanity, and should, I believe, honour that trust. Obviously, one makes images in order to have one’s say – photographers no less than painters, film-makers, or poets. Arbus clearly had a compulsion to tell her story, probably a greater compulsion than most of her unknowing subjects. However, the story she had to tell about herself could also be told about her subjects – a story of alienation, loneliness, sadness, resilience, and courage. And here, she was surely with her subjects rather than against them. Without flattering or patronising them, without compromising her own feelings (we know exactly who she was for and what she was against), without prejudicing her position in the photographic avant-garde, Arbus fabricated an imagery that would seem both report and self-portrait, both confession and indictment, a cri-de-coeur upon her own behalf but also upon behalf of the photographed.

Sontag contends21 that Arbus’s view was always from the ‘outside’, that of the privileged insider looking lecherously at society’s outsiders. Arbus, she maintains, was a pseudo-outsider. I would say, rather, that Arbus’s view was from both inside and outside. She certainly maintained the artist’s crucial detachment, that of consciousness and intent. There is, however, enough evidence to conclude that, like many of her subjects, Arbus stood in the world somewhat ‘precariously’, perfectly situated to empathise fully with her sitters. In her private life, there seemed an increasingly uneasy dichotomy between two worlds, between the upper middle class, Jewish milieu of her family, and the cosmopolitan, raffish fringes of Greenwich Village bohemianism. One can concur with Sontag22 that a strong whiff of épater le bourgeois pervades Arbus’s work. There are clear elements of rebellion, guilt, and revenge, the standard poor little rich girl scenario of thumbing her nose at her parents, of exorcising her husband and her failed marriage. But can we make too much of this? And interestingly, do we make too much of it simply because Arbus was a woman? Do we – female commentators included – practice an unwitting sexist double think in this regard? No one has ever accused Robert Frank of the same kind of guilty retaliation, though he was another Jewish bohemian of middle class origins with a chaotic private life, another social photographer with a political programme as non-existent as that of Arbus.

Sontag contends that Arbus’s view was always from the ‘outside’, that of the privileged insider looking lecherously at society’s outsiders.

Yet the notion of Arbus’s view as specifically a woman’s view does have some credence. Her psychological frailty has been utilised frequently to explain the work, but art historian Kathleen Campbell23 and others have offered a contrary, more positive theory. They have argued that Arbus ‘went against nature’ by usurping a typically male role, the Baudelairian flâneur, the urban ‘stroller’. For Baudelaire, the flâneur was the epitome of contemporary urban man, casually strolling the city pavements, carefully maintaining both his anonymity and psychological distance in the crowds, taking in the myriad acts of street theatre with the disinterested eye of the practised voyeur. Here, we might begin to see where Arbus was the genuine outsider in societal terms, appropriating an essentially male perogative – that of staring. And as Nancy Henley reminds us, the very act of staring is an overt display of masculine power:

‘Staring is used to assert dominance, to establish, to maintain, and regain it.’24

By appropriating, and also subverting such a powerful and almost exclusively male convention, by conspicuously demonstrating such an independent ‘free’ spirit, it is not surprising that Arbus’s pictures shocked so much, and still remain dangerous. It is hardly surprising that she attracted so much negative comment, of the inordinately vituperative kind that dogged her career, and which has continued, unabated, after her death – far more negative comment than the work itself surely merits, despite its admitted problems. As Sarah Kent has noted with regard to masculine conventions, imagistic or otherwise:

‘One challenges these conventions at one’s peril. For they are not merely annoyances to be circumvented with care and sensibility, nor just an example of one individual imposing authority or asserting dominance over another in a person to person encounter. Underlying these trivial social limitations are much more profound restrictions on looking and enquiry.’25

At last, we might locate a programme for Arbus, a critique of orthodox ‘insider/ outsider’ relationships with, as the more perceptive critics have noted, a particular subversion of gender relationships. For if Arbus denotes vertical divisions in society by articulating classes of stigmatised and non¬stigmatised, she cuts horizontally, so to speak, across this schema in her treatment of gender. Whether depicting the self-satisfied middle classes or the psychologically frail margins, she invariably pictures her women as stronger than her men. The natural warp is a lot more twisted in Arbus’s male of the species. Ian Jeffrey writes:

‘The women of Diane Arbus may be unsettling, near savage in one or two cases, but they are positive and certain in their femininity where the Arbus men are almost without exception pathetic and ludicrous. If not actually intimidated many of the men act and dress as women. It is a world turned upside down where the truck driver paints his nails and wears a slip whilst the Lady at a masked ball with two roses on her dress, NYC (1967) has the build and charm of an all-in wrestler. As a composite picture of the American people it is a mocking denial of the American archetypes we have learned to recognise.’26

Arbus might be the paradigm of the psychological portraitist, exploiting her subjects to a degree by utilising them as sounding boards through which she could plumb the depths of her own psyche. Yet the psychological is seldom wholly divorced from the social, and Arbus surely recognised this, intuitively and artistically. She used this insight to create a gallery of American characters that, on a perhaps narrower but no less epic canvas, echoes August Sanders’ heroic characterisation of Weimar Germany. Diane Arbus fashioned her own, cogent critique of American mores, enlivened by an absorbing inversion of finite sexual roles and gender imperatives. Her view was complex, highly individual, perhaps a little perverse, but never perverted – a sad, moving testament to the human condition.

Notes

1. Susan Sontag, On Photography (Farrar, Straus and Giroux Inc., New York, 1977). Pages 64-65.

2. Ibid., page 29.

3. A. D. Coleman, Light Readings: A Photography Critic’s Writings, 1968-1978 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1979). Page 126.

4. Sontag, op. cit., page 41.

5. Diane Arbus, quoted in Sontag, op. cit., pages 12-13.

6. Sontag, op. cit., page 13, page 42, and page 40.

7. Ian Jeffrey, Diane Arbus and American Freaks, in Studio International (London), March 1974, Vol. 187, No. 964. Page 133.

8. Ibid., page 134.

9. Sandford Schwartz, A Box of Jewish Giants, Russian Midgets, and Banal Suburban Groups, in Art in America (New York), November/December, 1977. Page 68.

10. Ibid.

11. Sontag, op. cit., page 37.

12. Alfred Appell Jr., Signs of Life (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1983). Pages 128-129.

13. Diane Arbus, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture Books Inc., Millerton, N.Y., 1972). Unpaginated.

14. Marvin Israel, in Diane Arbus: Magazine Work (Aperture Books, Millerton, N.Y., 1982). Page 5.

15. John Szarkowski, Mirrors and Windows (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1978). Page 13.

16. Amy Goldin, Diane Arbus: Playing With Conventions, in Art in America (New York), March/April, 1973. Page 73.

17. Diane Arbus, Monograph, op. cit., quotation from tape of masterclass.

18. Jeffrey, op. cit., page 134.

19. Diane Arbus, Monograph, op. cit., quotation from tape of masterclass.

20. See Irving Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (Prentice- Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1966, and Pelican Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, 1968).

21. Sontag, op. cit., page 42.

22. Ibid., page 44.

23. Kathleen Campbell, The Heroes of Modern Life: Diane Arbus and the Nineteenth Century Origins of Modernism. Paper given at the SPE Conference, Hotel del Coronado, San Diego, California, April 14, 1987.

24. Nancy Henley, Body Politics (New Jersey, 1977). Page 166.

25. Sarah Kent, Looking Back, in Sarah Kent and Jacqueline Morreau, Women’s Images of Men (Writers and Readers Publishing Co-operative Society, London, 1985). Pages 56-57.

26. Jeffrey, op. cit., page 134.

(Text reprinted with the permission of Gerry Badger. Text © copyright Gerry Badger and ASX. All Diane Arbus images © copyright the photographer estate and/or publisher)