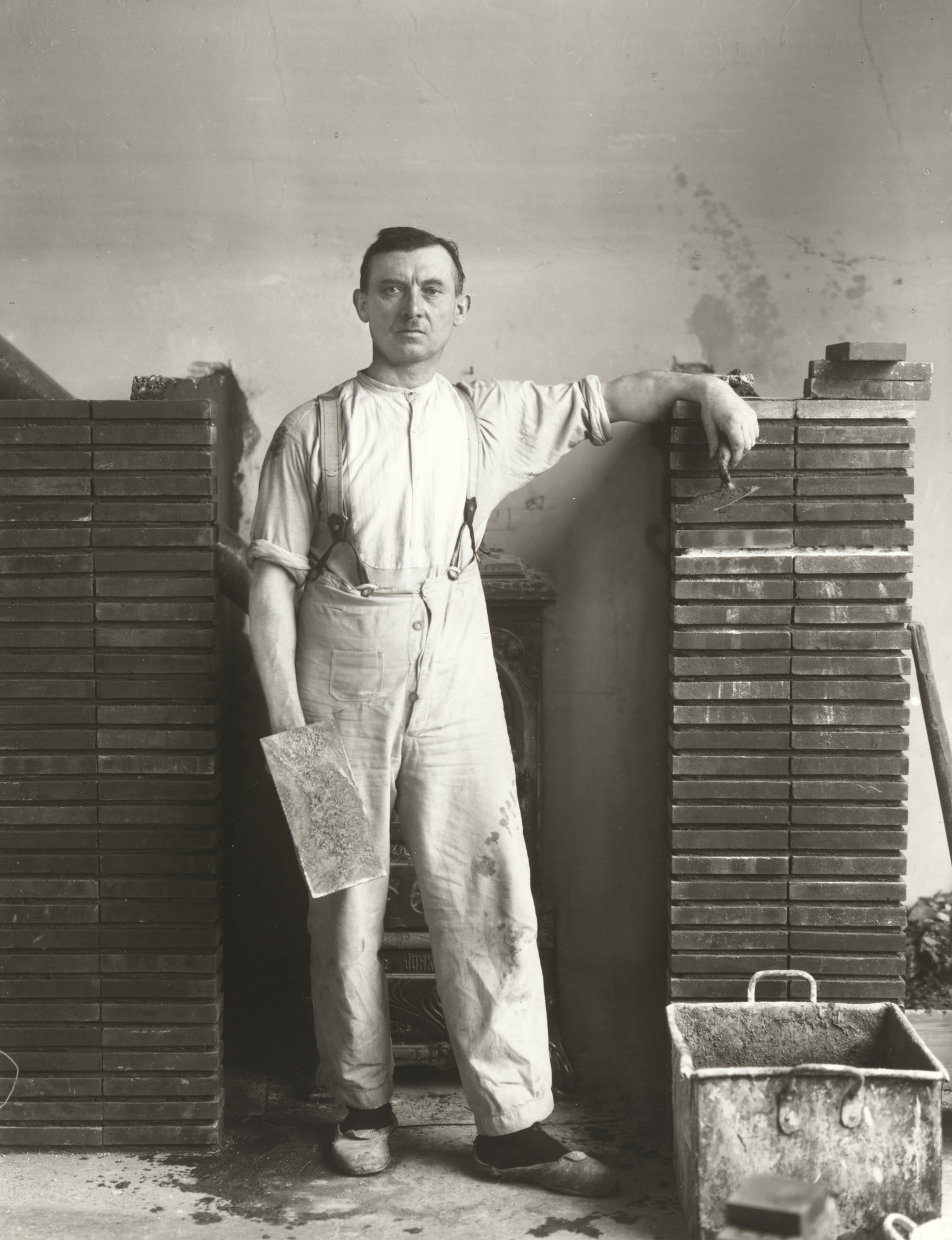

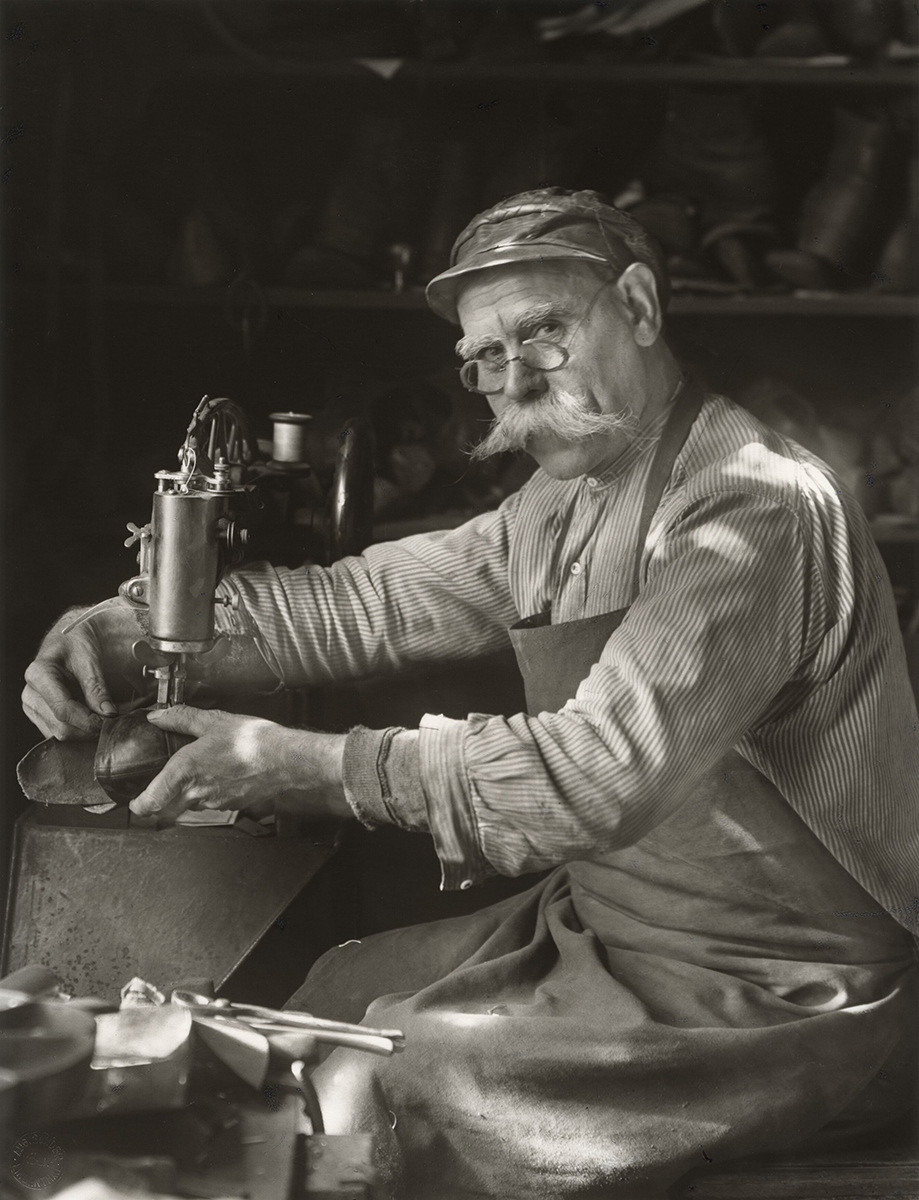

In 1910, August Sander began a systematic attempt to portray and typologize his fellow countrymen. The project, undertaken wholly at his own initiative and expense, found support only among his painter friends in the Rhineland area of Germany. His book Antlitz der Zeit was outlawed and partially destroyed by the Nazis in 1936, but Sander’s ambitious undertaking today ranks among the most outstanding contributions to the New Objectivity in photography.

The parameters are fairly clear: August Sander titled his picture Young Farmers, 1914, thus indicating both the date of the photograph and the social status of the subjects. But whether the picture was made before or after the outbreak of the First World War, felt by many of his contemporaries to mark the end of an epoch, seems not to have been particularly important to Sander. Where the three young men are coming from, or where they are headed, also remains unknown. Are they brothers? friends? neighbors? It has often been claimed that the three are on their way to a dance in town – which at first seems a reasonable assumption. But surely the weekend or even the end of the workday offer additional grounds for ‘young farmers’ to wash themselves, shave, comb their hair, and draw the dark suit out of the closet. At any rate, we can be sure that the trio have a common goal. But for the moment they let it slip from their minds, as they stop and turn, looking at us directly almost as if on command – and thus make us aware of another person, also present in the photograph without being visible: the man behind the camera. At the time of the photograph, August Sander was thirty-eight years old. As the Wilhelmine Empire neared its end, he had the reputation – along with Hugo Erfurth and Hugo Schmolz – of being one of the leading photographers in Cologne. In Bavaria or Prussia, he probably would have sought the status of court photographer; in the bourgeois Rhineland, however, he attempted to prove that he was among the best through the quality of his work and the correspondingly high prices he could ask for it. Was it the loyalty of the Rhineland bourgeoisie to the older, long established studios, or was it Sander’s understanding of the recompense he deserved for his photographs, that soon forced him to look for customers outside of Cologne? In any case, it is certain that Sander increasingly found his clientele in the nearby Westerwald region – a situation that could hardly have displeased him, since Sander, who had come from a simple background himself, had a great understanding and appreciation for the area and undoubtedly struck up a sympathetic relationship with the farmers who lived there.

Whether the negative numbered 2648 was the response to a portrait commission, we do not know. Nonetheless, the name of a certain Family Krieger is known – and nothing else, except that they were to be sent a dozen copies of the photograph: “12 cards” is noted by hand on the negative – probably a reference to printing them in the 4 x 6-inch cabinet format. What might at first glance be misunderstood as ‘instantaneous’ photography is therefore actually the result of a carefully composed scene, probably preceded by Sander’s intensive preparatory conversation with the subjects. In other words, he and the young farmers would have chosen the location of the photograph, decided in favor of a group portrait, and set the specific day and time. Neither the fact that the photograph was made in the open air, nor the make and age of the camera – which first had to be carried to the site, fastened to a stand, and set up for the photograph – probably struck the men, inexperienced as they were with standard photographic practice, as unusual. Sander himself explained nothing: in his remarks and theoretical explanations he was always remarkably reticent. In 1959, however, at an exhibition in the Cologne Rooms of the German Society for Photography, Sander, asked to comment on his picture, offered only technical details about the camera and chemical processes – not at all unusual for the times, but amazing for the “artist” August Sander. “Ernemann portable camera 3/18,” he noted about the Young Farmers; “built-in Lucshutter release – time exposure no diaphragm – lens: Dagor, Heliar, Tessar, old lenses – Westendorf-Wehner plates – development meteolhydrochinon or pyro daylight.”

Sander’s Young Farmers (original negative format: 43/4 x 61/2 inches) contains a good many oddities and contradictions. But these characteristics are probably precisely what make the picture so interesting and have made it into the most-reproduced and most well-known of Sander’s photographs. Sander, it is often said, constructed his pictures in archetec-tonic fashion, giving his subjects sufficient time to present themselves in an arrangement that felt right to them. In fact, the group portrait of the three young farmers oddly creates a simultaneously static and active impression, almost with a trace of the cinematic about it. A cigarette is still hanging loosely from the lips of the young farmer to the left; the one in the center is holding a cigarette in his hand, and the young farmer on the right has possibly already thrown his away. The young man to the left appears as if he had just stepped into the picture, an impression underlined by his walking-stick held at a slant, whereas the young farmer in the background seems petrified into a pillar, his cane boring perpendicularly into the earth, his gaze steadfast, even dogged. Whereas the other two have just arrived, he is already a making a face as if he wants to move on.

Contemporary art critic and theorist John Berger, who has subjected the photograph to a penetrating analysis, points out another peculiarity: the dark suits of the three young men. In terms of cultural history, the suit is an ‘invention’ of the bourgeois era. The replacement of courtly dress by a special costume developed specifically in England is above all a reflection of deep social changes. With the ‘suit’, the new bourgeois elite had created an appropriate uniform for itself: simple, practical, and egalitarian. At least for men, what was now important was less social prestige, as signified by an elaborate wardrobe, than economic success in capitalist competition. The suit is, as Berger expresses it, a costume for the “serene exercise of power” in which a man with a powerful build developed through hard bodily labor, appears “as if he is physically deformed.” And yet, as Berger correctly emphasizes, “no one had forced the farmers to buy these pieces of clothing, and the trio on their way to a dance are obviously proud of their suits.” They are even wearing them with a certain dash in Berger’s interpretation – an attitude which nonetheless does not relieve the contradiction, but rather lends an ironic accent to the picture.

The year 1914, when the photograph was made, undoubtedly marks a break in modern history. This was the year in which Sigmund Freud published his outline On the History of the Psychoanalytic Movement, Duchamp presented his “ready-mades” for the first time, Walter Gropius designed the Faguswerke that was to be so important for modern architecture, Albert Einstein developed his theory of relativity, and Charlie Chaplin made his first movie. For many historians, the first year of the war marks the real end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the increasing technological development, rationalization, tempo, and loss of individuality that characterize modernity. August Sander was almost certainly well aware of the change of paradigms – all the more so because leading exponents of what later came to be known as the “Rhine Progressives” – Heinrich Hoerle, Franz Seiwert, Anton Raderscheidt – numbered among his closest friends. Sander was born in 1876 as the son of a mine carpenter and small farmer in Siegerland. Whereas in his early years as a professional photographer he had subscribed entirely to an artistic approach to photography devoted to painterly ideals, by the time he moved to Cologne in 1910, he had transferred his allegiance to what he called “exact photography,” without softening effects, retouching, or other manipulations. These principles hold both for his commercial photography and for his ambitious portfolio Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th Century), that has long been recognized as one of the most significant contributions to the New Objective photography of the 1920s.

The idea of creating a cycle of portraits was not necessarily new. Nadar, Etienne Carjat, and the German photographer Franz Hanfstaengl had already introduced the ancient idea of a pantheon of important contemporaries to photography. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Erna Lendvai-Dircksen and Erich Retzlaffwere pursuing ‘folk’ or pseudo-racial investigations, while their contemporary Helmar Lerski experimented with the formal vocabulary of photographic Expressionism in his Kopfe des Ailtags (Ordinary heads). August Sander’s intentions were considerably more modern that those of his forerunners, in that he not only took notice of the immense social transformations that had occurred during the process of industrialization, but also made them precisely the basis of his social inventory of the German people. Sander has long been criticized for not organizing his work according to the latest knowledge of modern social sciences, but rather arranging his social inventory into seven groups and forty-five folders according to a more or less antiquated model of professional distinctions and hierarchies. The high number of representatives of certain ‘types’ does not at all correspond to the social reality of the Weimar Republic. In fact, the labor force as such is hardly included in Sander’s concept, whereas farmers, taken as a group that the photographer respected as ‘fundamental’, were clearly over-represented. The Cologne newspaper Sozialistische Presse, for example, apostrophied the figure of a huntsman as “ripe for a museum” and posed the question whether the work really had anything to do with representative examples of the twentieth century. Sander’s work, which remained unfinished, may in the end deserve particular criticism in view of the photographer’s claim to (‘pseudoscientific’) neutrality (Susan Sontag). But as a contribution to photography it remains unique. Approximately as the First World War drew to a close, August Sander turned his attention seriously to his self-appointed task, which he soon provided with the ambitious and encyclopedic title People of the 20th Century. Later he explained, “People often ask me how I came up with the idea of creating this work. Seeing, observing, and thinking – that answers the question. Nothing seemed more appropriate to me than to use photography to produce an absolutely true-to-nature picture of our age.” Different from the artistic photographic portrait, Sander’s work was not an attempt to visualize inner values, but of interpreting social reality by photographic means. Farmers, craftsmen, laborers, industrialists, officials, aristocrats, politicians, artists, ‘travelers’, to name a few of Sander’s categories, step before the camera. Most of his subjects he found in his immediate Rhineland environment, a fact which today gives his work a slight regional flavor. Formally Sander followed his own, self-deter-mined standards, which do not necessarily make the photographs similar, but lend them a compatibility to each other. That is, he photographed by available light, and usually in a setting in which the subject felt at home. He handled his subjects as complete figures, selected a wide frame, and avoided extreme upward or downward shots that were popular in photography at the time. That in the case of Young Farmers, as with the majority of Sander’s motifs, only a single negative plate exists indicates that the photographer was relatively self-assured in his visual dialogue with his protagonists.

August Sander first garnered attention to himself in an exhibition in the Cologne Arts Association in 1927. Whether Young Farmers was on display in the show we do not know. But it is certain that older works, originally created as commissioned portraits, were in the meantime being gathered and selected with a view toward the creation of a portfolio that was already in the works. Sander now came to the attention of Kurt Wolff, who had previously published Renger-Patzsch’s highly regarded book Die Welt ist schon (The World Is Beautiful), and in 1929 Antlitz der Zeit (Faces of our Time) appeared as a first volume, intended as a commercial harbinger of the larger projected work to follow. According to an advertisement sheet included with the work, the volume of selections was able “to convey only a weak idea of the extraordinary size and range of Sander’s full achievement. What is does show, however, is the ability of the photographer to get to the core of the people that he places in front of his camera, excluding all poses and masks, and instead fixing them in a completely natural and normal image.” In Antlitz der Zeit, a full-page print of Young Farmers appears as Plate VI.

In other words, Sander had already selected the picture to be a part of the core of the ceuvre that in the end was supposed to comprise approximately five thousand plates. Exactly what caused the National Socialists to destroy the printing plates and the remainder of Antlitz in 1936 remains still somewhat unclear; similarly, we do not know why, after the war, Sander did not bring his project to a conclusion that would have satisfied him. It is clear that the photographer, now in his seventies, no longer possessed the same energy as earlier. Furthermore, his post-war living quarters in Kuchhausen, with only modest laboratory equipment, were certainly not the ideal place to finish a portrait work of this dimension in an appropriate manner. Nonetheless, Sander continued to work on the project for the rest of his life, taking up old photographs into the collection, and rearranging them all. In the process, he was accompanied by an increasingly interested public. The photokina fair exhibits of 1951 and 1963, as well as Sander’s participation in Steichen’s “The Family of Man” project (1955), were important early stations in his more recent reception. That the world had changed since the conception of the project can hardly have missed Sander’s notice. Where youthful gestures of protest might express themselves in 1914 through cigarettes and a hat askew, the world after 1945 sported chewing gum, rock and roll, jeans, and petticoats as signs of the modern spirit. In a certain sense, August Sander had lost hold of ‘his’ people.

Excerpt from: The Story Behind the Pictures (1827-1991): A Profile of the People – August Sander – Young Farmers 1914

ASX CHANNEL: August Sander

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher