Everything about him suggests an anarchic temperament, capable of playing any worldly system to the hilt and then throwing away its benefits.

Brought to ASX by Errata Editions. Full essay included in Books on Books #5 William Klein: Life is Good…New York!

By Max Kozloff, Excerpt from William Klein and the Radioactive Fifties, originally appeared in the May 1980 issue of Artforum

…Sleaziness is not the same as poverty, for all that they’re compatible deficits and Klein’s furor is not the same as social engagement. The world he depicts, which has come apart – fissures everywhere and eruptions of crud – was for him a visual discovery. He can be said, almost, to have invented it – at a propitious moment of our cultural history. For him, the streets were populated by hotshots, wiseacres, and meatballs, though a longer look shows that such thoroughfares teemed with harassed or strained people and anxious kids. Isn’t this like the first impression one gets when returning from Europe to New York: an indescribable filth, an unbearable pressure, and a disproportionate number of crackups aimlessly wandering about?

“On Forty-second street, posters in violent colors announced thriller-films – horror films – gay films. I stopped there. On either side of the box office, distorting mirrors reflected the passersby; they were long and broad. I looked at myself; I was on the point of making faces; fog rolled in my brain…”

The above by Simone de Beauvior from her journal of the 1950s, America Day by Day, sums up quite well the wide-angle atmosphere of Klein’s New York. More than that, it suggests the vertigo induced by the spectacle he makes of it.

Klein certainly had as much of de Beauvior’s wonder, none of her sour crotchets, and a different sort of animus. While he soft-pedals it now, he must have been affected by the anti-Americanism of the French left, though not by its brittle Stalinism. Everything about him suggests an anarchic temperament, capable of playing any worldly system to the hilt and then throwing away its benefits. With his hometown, New York, to which he returned at the age of twenty-six, he appears to have had a score to settle, expressed through a photography of ecstatic and ravished vengeance.

“This city of headlines and gossip and sensation,” Klein said. “…needed a kick in the balls.”

He literally blitzed the place in about six months. The full title of the book containing the results of this astonishing campaign (published only in Europe, 1956, and usually referred to simply as New York) is Life is Good and Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels. Mangling a tabloid phrase that might have been “Chance Witness Reveals,” the words signal not only a playful mind but a surreal impact that must have been much more concrete for Klein here than in postwar Paris.

“This city of headlines and gossip and sensation,” Klein said. “…needed a kick in the balls.” As he told John Heilpern, for an essay in William Klein: Photographs, the Aperture monograph on his work;

I saw the book as a monster big-city Daily Bugle with its

scandals and scoops that you’d find blowing in the streets

at three in the morning…. For me photography was good

old-fashioned muckraking and sociology… I could imagine

my pictures lying in the gutter… I was a newspaperman!

Or a Frenchman. One time in Harlem I cooled things

down by saying I was French. “Hey! This guy ain’t white.

He’s French!”

It’s interesting to make the obvious comparison between Klein and Weegee, who had a comparable stake in a squalid New York and who really was from the News. Linking them like this, one sees immediately that – aside from the similarity of their supreme voyeurist chutzpah – one was a primitive putting on airs, while the other was a modernist slumming with jazzy abandon. There is hardly anything like the real-life murder-and-mayhem of the journalist in Klein (only toy guns and charades of violence), and there is nothing of Klein’s extreme artistic rawness visually decomposing before your eyes in Weegee. This is not simply the difference between parochial spirit and cosmopolitan vision. The real contrast emerges in their attitudes toward the media, which both exploited, but for opposite reasons.

Klein, for his part, was an uncontainable aesthetic guerilla who made use of corporate sponsors for purposes at the edge of their taste, testing the axiom that the more they funded the more he could provoke.

That to which Weegee frustratedly aspired, the status of artist, was the easiest thing for Klein to shuck off, because he has an artistic identity as a painter from the first. Weegee blazed out space for his Expressionism in a genre that, for all outward appearances, kept him a colorful hack. Klein, for his part, was an uncontainable aesthetic guerilla who made use of corporate sponsors for purposes at the edge of their taste, testing the axiom that the more they funded the more he could provoke. The entry of both men into the fashion world (a few shots by Weegee and a longer stint by Klein) coincided with the moment when editors decided they liked the frisson of models seen in working-class milieux. Coming from such precincts themselves, the photographers could have had only a volatile response toward such a condescending program (the have-nots as backdrop).

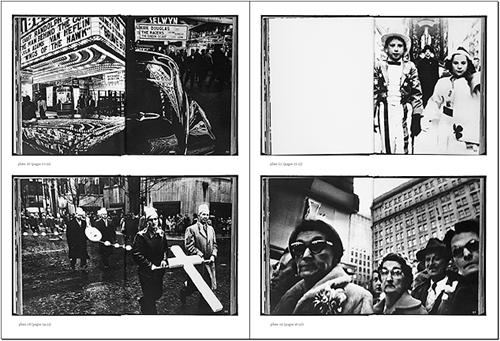

Weegee worked within the illustrative confines of tabloid graphics with hypertensive pointedness, while Klein diffused their headline and layout strategies into his street shots. Abounding with billboards, signs, and hard-sell messages of every sort, his pictures are, in fact about media as much as they deal with people who are targeted by them (Fig. 2). Everything within his frames grabs at your attention, the more incongruous, grotesque, or disjointed the presence, the better. At the same time, he was no more a muckraker than a Frenchman, just as it’s clear that he had great aptitude but no final calling for painting or fashion photography. Like Weegee in his fun-house mood, ultraquick reflexes and unstanchable energy that spilled over into such modes as film, Klein differed in that he had no psychic base.

No one acted the poseur with more conviction.

We’re entitled to ask what a figure with such equivocal resources contributed to the art of photography. Of late, the medium, during the 1950s, has been considered to have been pretty much a one-chicken town – the chicken being Robert Frank…

Continued in Books on Books #5

Books on Books #5

William Klein: Life is Good…New York!

Essays by William Klein, Max Kozloff, Jeffrey Ladd

Hardcover w/ Dustjacket

160 pp, 9.5 x 7 in.

120 Duotone illustrations

ISBN: 978-1-935004-08-0

$39.95

ASX CHANNEL: William Klein

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow ASX on Twitter.

For inquiries, please contact American Suburb X at: info@americansuburbx.com.

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher