The picture-taking nomad was so awed by the charm of Brazil’s former capital and its citizens that, over the next 50 years, he chose it as the center of his life and as his base and starting point for countless trips to Africa.

Introduction to Pierre Verger – Black Gods in Exile

By Manfred Metzner and Michael M. Thoss

The Pierre Verger Foundation lies in one of the rapidly expanding suburbs of Salvador da Bahía not far from the expressway Vila América, with which the coastal town spreads its feelers deep into the hinterland. What was once Verger’s private residence, purchased by the worldly photographer in 1960, today houses his immense archive with photographs spanning four decades and five continents.

A few years ago, when we visited the one-storied house for the first time, it seemed as though its inhabitant had stepped out for a moment, or was on one of his many trips: in the afternoon heat the shutters were closed over windows without panes of glass; his broken eyeglasses, held together by strips of adhesive tape, were left on the wooden writing table; and beside this was the narrow, covered bed that he installed during his last years. In a bureau was Verger’s handwritten correspondence. His extensive private library was arranged on metal shelves. And the archive cabinet, overflowing with countless negatives, attested not only to his ascetic lifestyle and sense of order, but also to the respect of the many friends of this master photographer who died in 1996.

Today the majority of the circa 62,000 surviving negatives exist in a digital format and are even accessible on the homepage of the Fundaçao Pierre Verger. On entering the foundation, visitors are received by a friendly coworker as well as by the vast number of books and catalogs the foundation published over recent years. One learns that Pierre Verger’s spirit has even returned to the old quarter of Salvador, where, not far from his first apartment located in the Pelourinho, the foundation opened a photo-gallery a few months ago.

In August of 1946, when Pierre Verger disembarked from the steamer arriving from Rio de Janeiro and set foot on land in Salvador, in his heart he had already taken leave of Europe and the grand society of Paris from which he came. The picture-taking nomad was so awed by the charm of Brazil’s former capital and its citizens that, over the next 50 years, he chose it as the center of his life and as his base and starting point for countless trips to Africa. He was warmly accepted by the art bohemia of Bahia, and was soon a close friend of the writer Jorge Amado, the sculptor Mario Cravo, the painter Carybé, and the folk singer Dorval Caymmi. The possibility of being accepted by strangers and merging with their community was a basic condition crucial to Verger’s photographic work. In addition, for a European fleeing the effects of World War II, Bahia probably suggested the counter-image of a continent marked by war and genocide: “All throughout Brazil one finds a generous and tolerant spirit. In Bahia, however, the race relations seem to produce the greatest human warmth. All religious expressions enjoy a far-reaching tolerance here, so that the cult surrounding certain African deities can be maintained with an impressive authenticity…” [1]

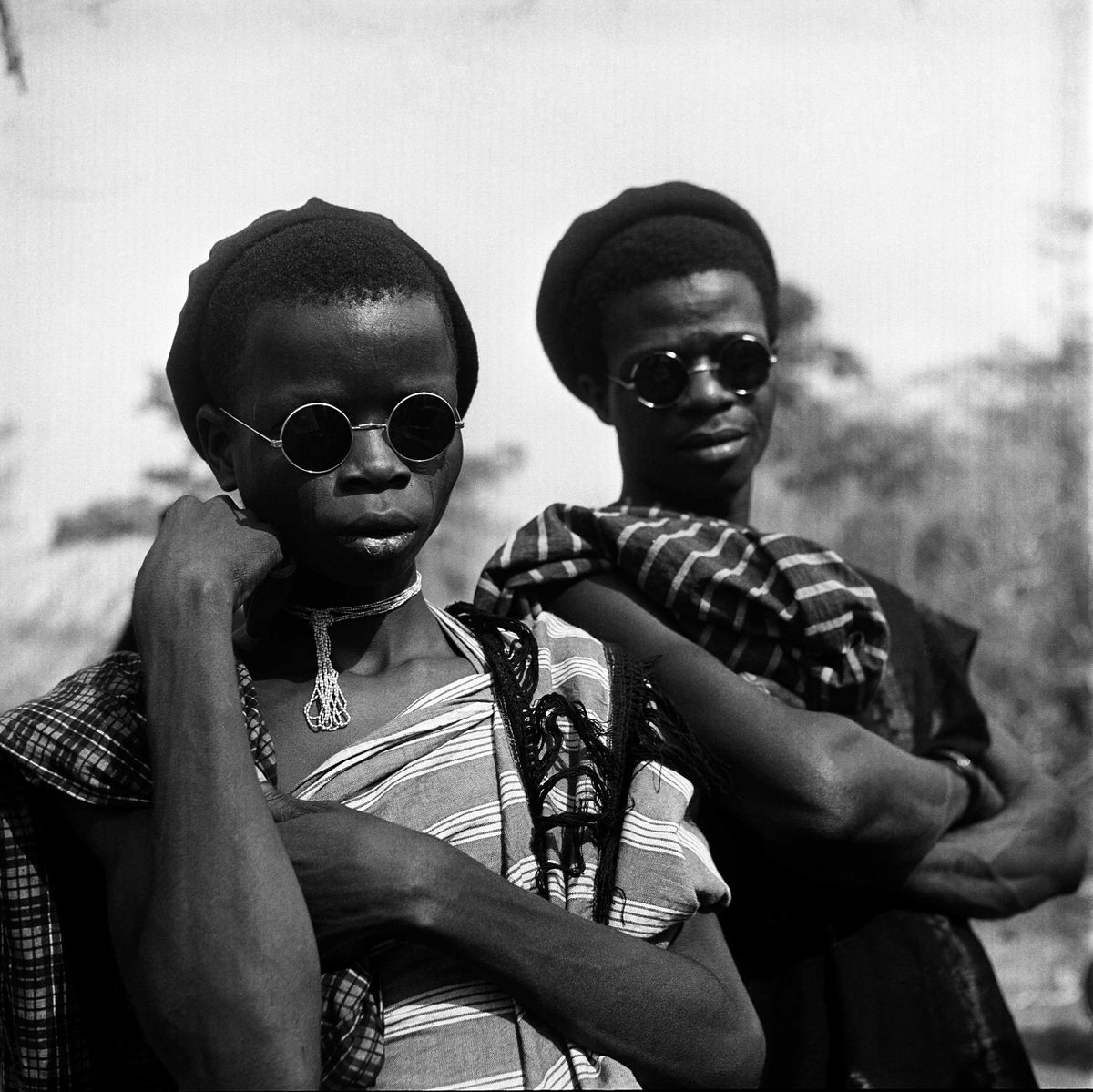

Capoeira, Salvador, Brasil, 1946-1959

Capoeira, Salvador, Brasil, 1946-1959

With great diversity, Verger’s work illustrates how up into the present the common African heritage in Brazil, the Caribbean and North America finds expression in music, dance and architecture as well as in art and cuisine. In his fascinating photographs and writings on Afro-Brazilian and Caribbean religious communities, Verger describes the reciprocal influences in the transatlantic triangle up into our current period. According to UNESCO findings, between 12 and 15 million slaves were deported by Europeans into the so-called New World, with circa 40% of them taken to Brazil. The collected memory of this atrocity – the greatest theft of human life in world history – was kept alive in ritual practices of the Brazilian Candomblé *), Haitian voodoo, and Cuban Santería. Verger realized how through such practices both sides of the Atlantic engage in a cultural exchange with one another since almost four centuries.

In present-day Europe, Pierre Verger is still unknown to a broader audience. One reason for the delayed reception of his work could be Verger’s modesty. He never gave serious thought to commercializing his photographs. For him, photojournalism was only a bread-and-butter job that allowed him to continue his private research on African deities in the New World. In Germany, in the mid-1970s, readers first became aware of him through Hubert Fichte and Leonore Mau, following the publication of collage-like impressions of Brazil, Haiti and Trinidad by these authors, under the titles Xango and Petersilie (Parsley). Verger’s archive served as a source of inspiration for their research, and, if one believes the foundation’s colleagues, it was through Verger that Fichte and Mau first gained access to the Candomblé ceremonies and their highest-ranking dignitaries. Later, of course, the reclusive photographer felt deeply offended when Fichte outed him in his text as a homosexual, after which the name of the German writer was taboo in Verger’s presence. Today one could call this a missed chance inasmuch as Fichte’s work, as a “poetic anthropologist,” was the aesthetic approximation of Verger’s to his own subject and almost akin to it.

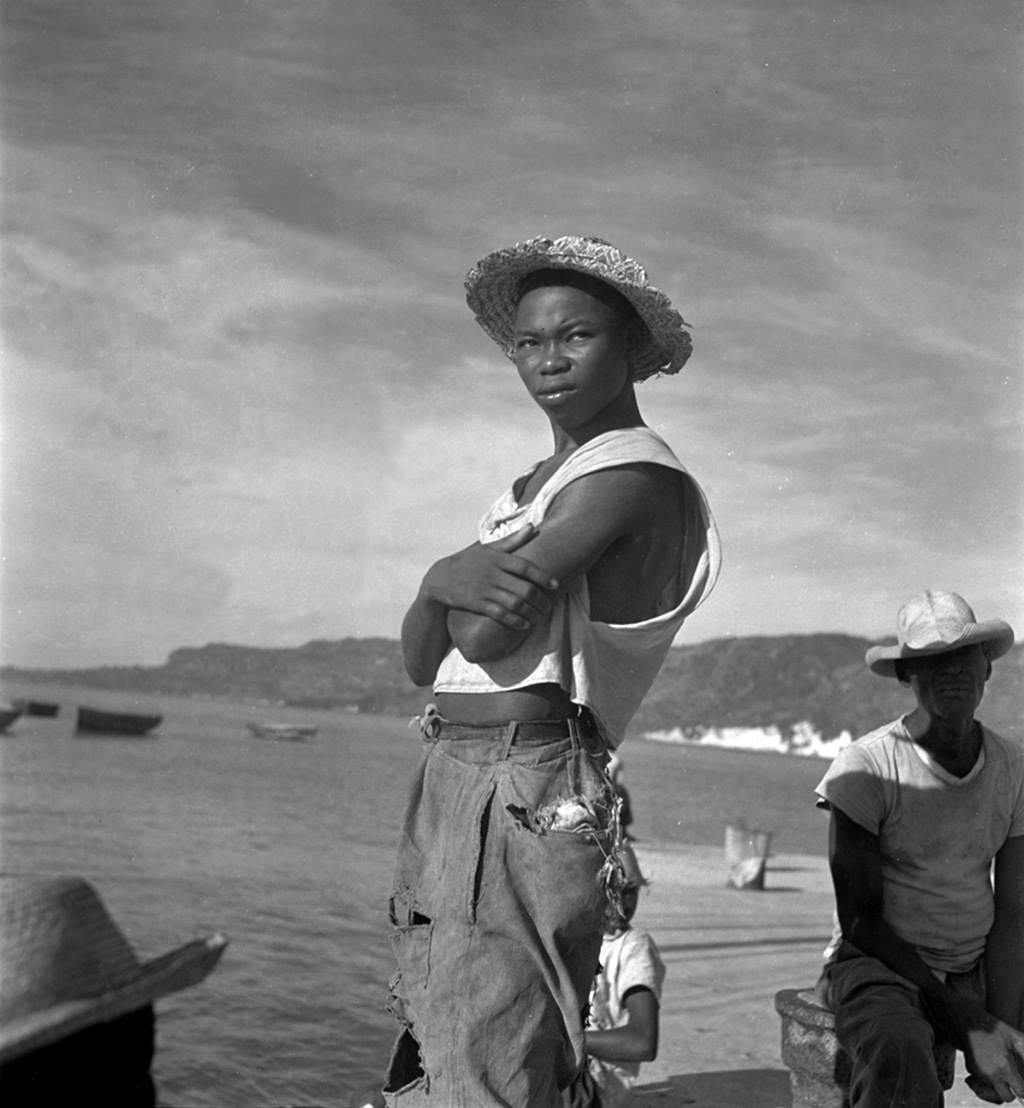

Mercado Modelo, Salvador, Brasil, 1946-1959

Mercado Modelo, Salvador, Brasil, 1946-1959

Verger’s intuitive “turning toward his subjects” stands for an ethical, basic stance in the making of his photographs.

Unlike the friends also ethnologists from the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, Roger Bastide and Alfred Métraux, who often gave him their texts to correct, Verger’s approach was deliberately undetached. He was the opposite of an aloof observer; he never used the lens of his camera as a partition between the observed object and the subject being interpreted. Moreover, his almost obsessive attempts to escape the middle-class milieu, and to subject himself to extreme situations, prompted him to always see himself as a part of his own experimental arrangement. There was method in his empathy. He never saw sympathy and shock as obstacles; they were the motivating forces of his understanding that enabled him to place himself in the position of the other; to overcome ethnic, social and epistemological barriers, and to experience in this way – recalling Rimbaud – oneself as the other: “To be honest, I’m only marginally interested in ethnography. I don’t want to study people as if they were just beetles or exotic plants. On my journeys, what I like is living with people and learning their different lifestyles. That’s because I’ve always been interested in what I never was, or in what I could be with others.” [2]

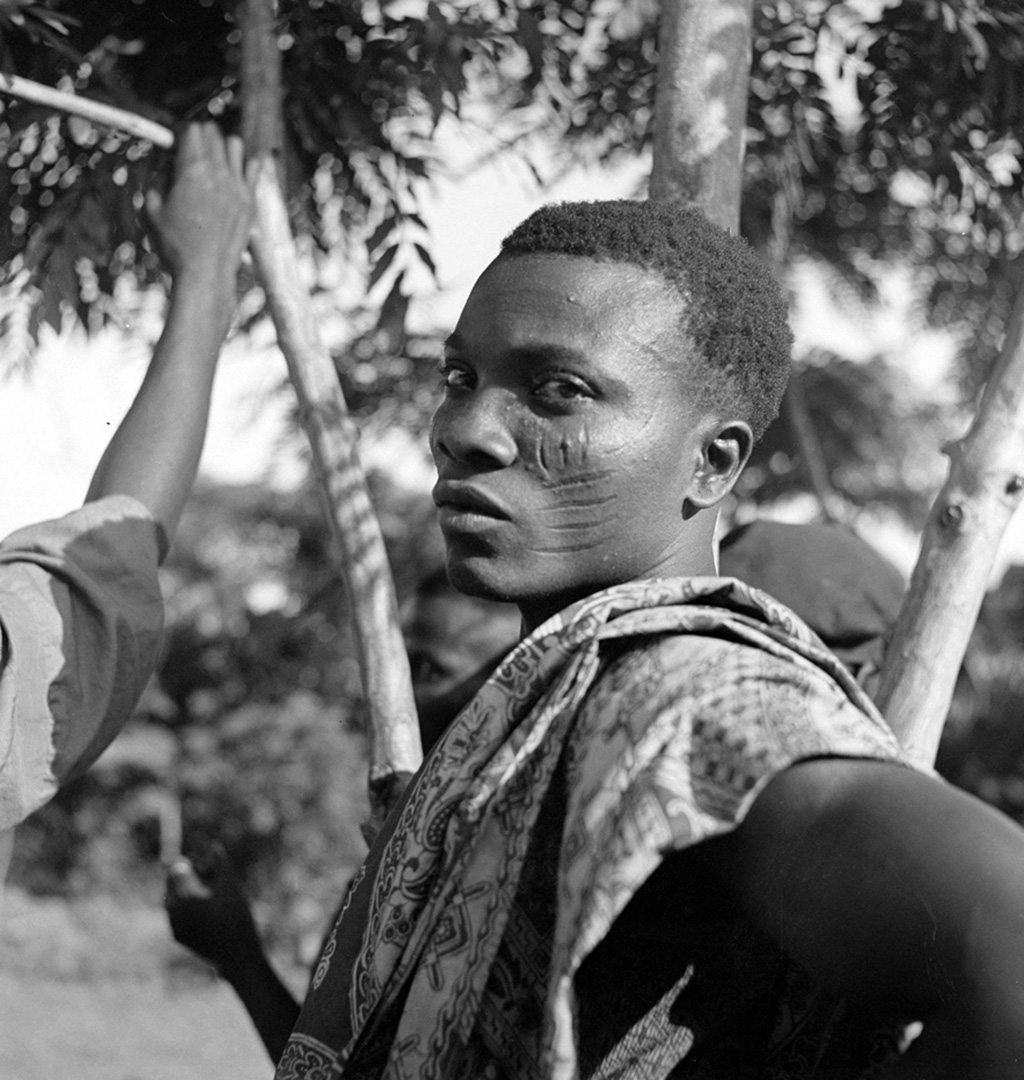

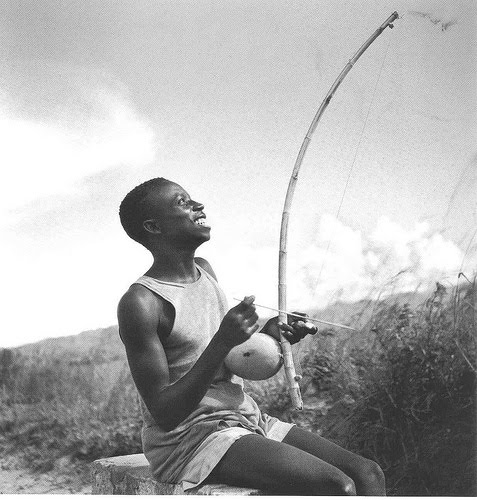

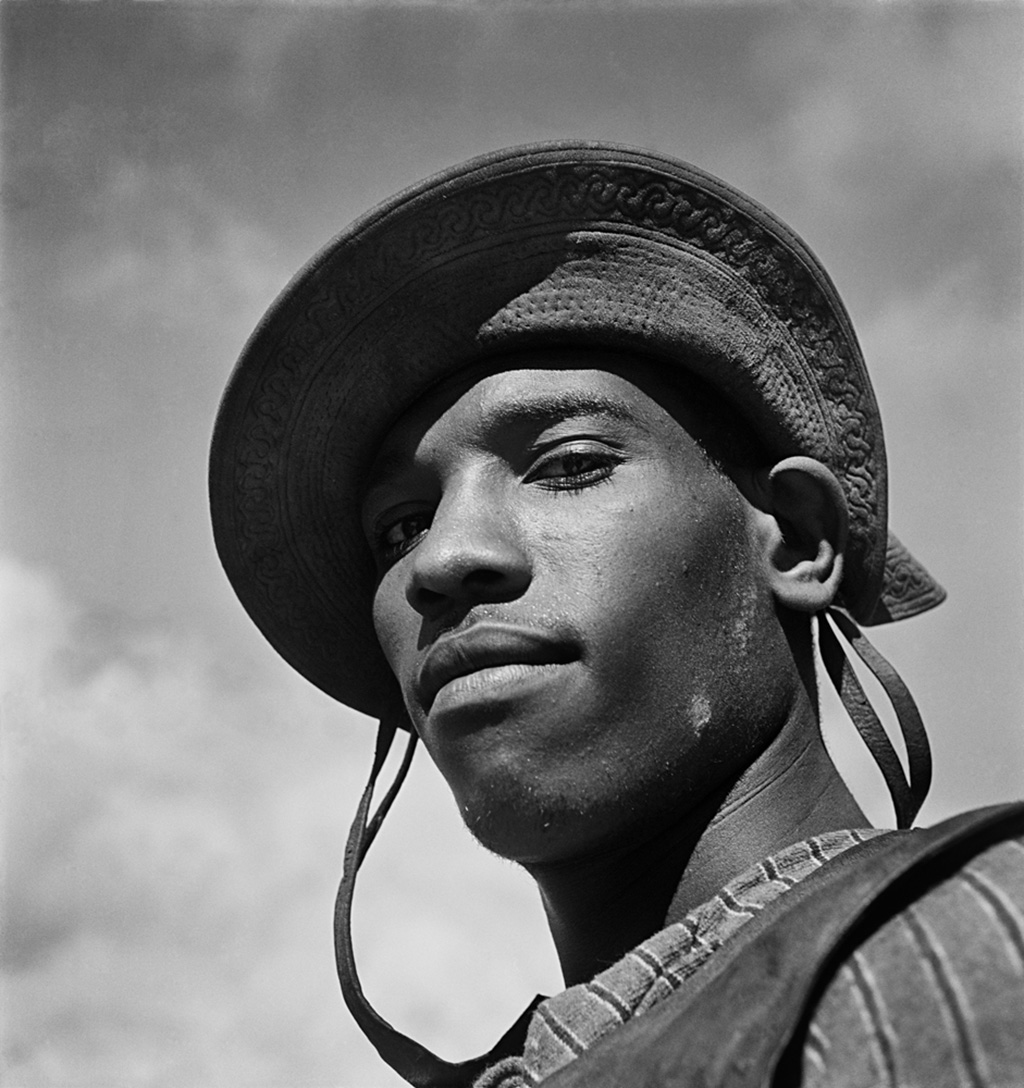

Verger’s intuitive “turning toward his subjects” stands for an ethical, basic stance in the making of his photographs. This expresses itself in his portrait studies in particular. His photography radically differs from ethnographical photography based on measured gestures and the obscene gaze directed at the object being photographed. By comparison, Verger had an aversion to voyeurism; the subjects of his portraits were never, so to speak, stripped bare. Even when documenting the poorest of living situations – like on his first journey to Africa in 1935/1936 – the people he photographed maintained their personality and dignity. The ascending camera angle, captured with his Rolleiflex hung from his neck, symbolically reflects Verger’s own gaze: instead of looking down at people, the lens of his Rolleiflex gazes up at them and grants the person being photographed an almost heroic aura.

Doumé, Benim, 1948-1958

Doumé, Benim, 1948-1958

Verger’s remarkable ability to adapt to his surroundings and transform himself “toward” people reached its height in 1953, when he participated in the Babalao initiation ceremony in Ketou (today Benin) and took on the new name of Fatumbi. This act of “rebirth” as another – as documented in Verger’s letters and writings – made a number of his academic colleagues doubt his credibility. Théodore Monod, director of the Institut Français d’Afrique Noire (IFAN) in Dakar, also Verger’s employer, informed him with tersely chosen words that the research money was not put forward in order to turn French ethnologists into “new pagans”. If not somewhat tragically, Verger’s photography paid the price by losing a portion of its suggestive power, when he began his academic work and prepared his doctorate on the slave trade between the Golf of Benin and Salvador da Bahia, completed in 1996. On the other hand, his Babalao title and the adjoining right to practice the Yoruba divinity cult’s Opele Ifa brought him great esteem in Salvador’s Afro-Brazilian religious communities. The founders of Bahia’s first Candomblé *) cult were, after all, said to have originated from Ketou, also considered the spiritual homeland of most Orisha *) cults.

Over the following years, Verger became transatlantic ambassador of the Bahian Candomblé community in West Africa. Up until 1979, he made as many as thirty trips to Africa. He presented his photographs and audio recordings of Candomblé rituals made in various traditional Yoruba communities. As a countermove, he recorded the Orisha *) myths and cosmogonies passed on orally from generation to generation. In this way, Verger managed to once again intensify the relationships on both sides of the Atlantic, after a considerable stretch of time, by making clearly visible the origins of the Afro-American Candomblé *) cult, voodoo and Santería, and their present-day relevance, as well as their ability to adapt to their respective society. By showing how the deification of the Orishas *) in the New World could be traced to historical figures in Africa, Verger became virtually indispensable as a genealogical-tree researcher for the dignitaries of Salvador’s religious communities, prone to compete among themselves. Eloquent proof of this is found in his masterpiece Flux und Reflux [3] and in his essays on slaves sold into freedom, whose situations forced them to repeatedly crisscross the Atlantic, as with the legendary priestess Marcelina da Silva-Obatossi. So it often happened that, on returning from Africa, Verger was received at the airport by delegations of Bahian Candomblé who embraced him as their ambassador.

It ranks as a great service to history that Verger and his friend, Roger Bastide, documented how a cultural understanding of the Candomblé *) cannot be explained solely on the basis of historical origins or ethnic associations; how former black slaves on the other side of the Atlantic had to rather invent their culture, and how, in doing so, they also made a substantial contribution to the modernity of both Americas.

Kamaniola. Kivu, República Democrática do Congo, 1952.

Kamaniola. Kivu, República Democrática do Congo, 1952.

Undoubtedly fascinating for Verger about the black gods – often syncretized with Catholic saints in their American “exile” (Roger Bastide) – was their inseparable presence in nature, society, and the human psyche.

Undoubtedly fascinating for Verger about the black gods – often syncretized with Catholic saints in their American “exile” (Roger Bastide) – was their inseparable presence in nature, society, and the human psyche. In his book, Orixas [4] he not only compares the “Yoruba Deities in Africa and the New World,” as the subtitle states, he also assigns human archetypes to them. These archetypes allow individuals to establish a direct relationship to their Orisha *), and to find through him their rightful place in the religious community. In this godly universe there is no one and infallible god, under whose jurisdiction everything and everyone must be ordered. On the contrary, the Afro-Brazilian pantheon of the gods is dominated by a variety of clashing voices. One example is the highest-ranking god of the Yoruba and its Brazilian descendants, Olorun *), who hardly plays a role in the daily lives of believers. What little one seems to know about him is that he ordered his son, Oxala, to create the earth and sea, and the first pair of humans. But deeply human traits exist in this Orisha *) as well, a deity represented from time to time as a black Jesus, and while drunk on palm wine, Oxala nearly oversleeps his job to create the world.

The Orisha *) and their assigned qualities have complementary characters that penetrate all areas of life and make them rhythmic – from nutrition, education, traditional medicine to one’s love life. That the Candomblé practice the art of thinking in analogies and symbols is what sensually heightens the experiencing of myths during rituals, and gives believers concrete instructions on how to behave: “Naturally these myths are collective ideas that possess all the strength of tradition. At the same time, however, these are also ways of thinking, and used to comprehend reality with. The same applies to their adjoining rites, which depict the process of mastering reality.” [5]

Verger’s relevance rests on the fact that he understood religious practices and cultural syncretism in the African Diaspora as being strategies for finding one’s identity and ways to embrace reality. In the years of the decolonization period, he saw Afro-Brazilian society as a counter-model to European colonialism and racism on the one side, but also as a counter-model to the mounting, ethnic nationalism in Africa’s newly-emancipated countries.

What particularly fascinated Pierre Fatumbi Verger about worshipping the Orisha in the New World was its underlying and founding, cultural concept, which refused to be determined or reduced by geography, class and race. And by making himself – as a European – a part of the Afro-Brazilian lifestyle and faith that he described, Verger could effectively test their power of assimilation and universal character. Granted his experiences have to be seen in their historical context. Today his enthusiasm over the “joyful melting together” of the races, which he believed he saw in Bahia at that time, might sound for many totally idealized. Just the same, his photographs and studies reveal to us a model for social integration and a system of spiritual values, which now, in the age of ensuing holy wars waged by different fundamentalists, can well contribute to a tolerant understanding of multiethnic and multi-denominational societies.

Simultaneously, Verger’s work contains an inherent critique of Brazil’s self-understanding and self image, which nowadays gladly suppress their African heritage. Even though circa half of the population has African forefathers, and cultural minister Gilberto Gil intends to legally strengthen its presence in the media – where they form only 1% of the workforce – Afro-Brazilians remain grossly underrepresented, where leading political and economic positions are concerned. So perhaps Verger’s photographs even help Brazilians to overcome the TV-soap cliché of the dyed-blond Telenovela beauty.

Footnotes:

1. In: Camera, Nr. 10, Oktober 1954

2. Interview with Emmanuel Garrigues, in: L’Ethnographie , N° 109, S. 171; Paris Printemps 1991

3. Flux et reflux de la traite des nègres entre le Golfe de Bénin et Bahia de Todos os Santos, du XVIIe au XIXe siècle; Paris 1968

4. Pierre Fatumbi Verger: Orixas. Deuses iorubás na Africa e no Novo Mondo; Bahia, 1981

5. Roger Bastide: Le Candomblé de Bahia, S. 304; Paris 1958

6. From the findings of the Brazilian NGO Sociedade de Cultura Domabli

ASX CHANNEL: Pierre Verger

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow ASX on Twitter.

For inquiries, please contact American Suburb X at: info@americansuburbx.com.

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher